Who Is Paul Ryan? In House Speaker Race, Wisconsin Leader And Younger GOP Could Make For A More Conservative Congress

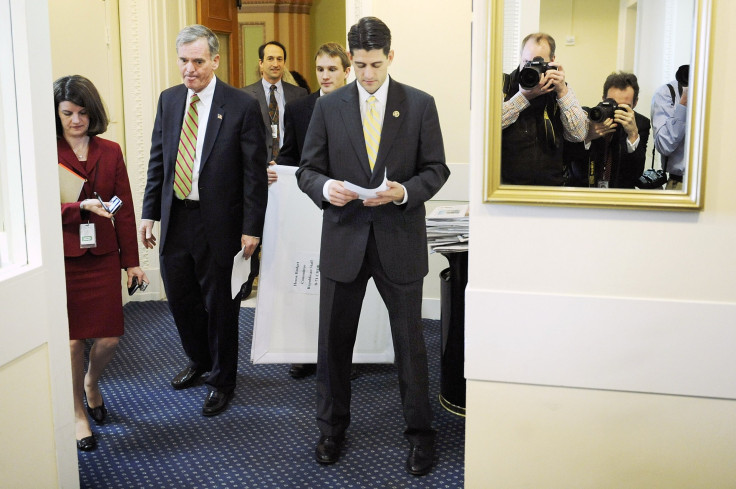

Behind closed doors Wednesday, Republicans in the House of Representatives could make history. Preparing to replace the outgoing speaker, the fractured and warring caucus is expected to choose Wisconsin Rep. Paul Ryan as its presiding officer, promoting him into political hallowed ground and placing him second in the presidential line of succession after the vice president. And, at just 45-years-old, he is also poised to become the youngest House speaker in 146 years.

Ryan's youth reflects a bigger trend in the House Republican conference: With each election since 2010, a fresh wave of congressional Republicans who are younger than their predecessors and unwilling to compromise on conservative issues have swept into Congress. That stands in stark contrast to House Democrats, whose ranks have a decided edge in the age department and who have repeatedly reached across the political aisle to broker deals. But, in spite of the relative youth of the Republican leadership in the House, millennials aren’t likely to throw their weight behind the GOP anytime soon, political experts said.

The major shift in the age difference between Republicans and Democrats came from the midterm elections in 2010. In those contests, House Republicans lowered their average age while Democrats saw theirs increase. Four years later, the average age of Democratic leadership was 64. For Republicans, it was 53.

“They’re definitely newer to Washington, the Republicans, because they’ve had these wave elections,” said Michele Swers, a professor in the department of government at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. “The House GOP has had a lot more turnover in recent years, so half the caucus has been there three terms or less, so you, in general, have a younger membership in the House Republican caucus.”

Ryan can take some of the credit for that shift: He helped to recruit that 2010 class alongside the likes of House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., and former Rep. Eric Cantor, R-Va. The trio co-authored the book "Young Guns," which called for a “new generation of conservative leaders.” Ryan is today considered to be closer to the center than that so-called "new generation" that was ushered in, but the influence of the House's far right has led to the partisan turmoil that forced current Speaker John A. Boehner, R-Ohio, to announce he would retire later this month.

The movement has also led to high levels of gridlock. After Republicans took over the House in 2010, the frequency at which legislation was tied up in Congress spiked to near record levels, according to evaluations by the Brookings Institution, a think tank in Washington, D.C. Part of the reason for that, experts argued, is because the newest congressional Republicans are less concerned with the complexities of the U.S. federal legislature and haven’t spent years schmoozing with their colleagues, forming relationships and finding common ground to strike deals. They want results, or they want nothing at all, which could mean more gridlock.

“I do think that they’re more ideological,” David Rohde, a professor of political science at Duke University, in North Carolina, said. “They’re more ideological in the general sense, which is they’re more extreme-right, but they’re more ideological in a different sense in that they’re less likely to be willing to compromise.”

Though Ryan is seen as being more moderate than the ultra-conservative, new wing of House Republicans, he is still further to the right of Boehner. He's already shown signs that he is less likely to work in partnership with Democrats. As Boehner prepared to leave his office later this month, he privately negotiated this week with House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and both sides of the Senate leadership to come up with a two-year deal to fund the government. Ryan, who was not a part of the talks, promptly blasted the secretive process Tuesday, the day after the budget was unveiled.

While those ultra-conservative lawmakers changed the demographics in the House, youth voting preferences were also shifting. Democrats dominated Republicans in terms of millennial support in both 2008 and 2012, two oddball years when President Barack Obama inspired young people to vote. But during the intervening midterms, that support dissipated, according to the Harvard Institute of Politics. Among likely millennial voters between the ages of 18 and 29 in 2010, Democrats were preferred by 55 percent to 43 percent. In 2014, that support switched and youth voters preferred Republicans 51 percent to 47 percent.

Still, a youthful House speaker and new House GOP conference that includes the youngest representative in the country, New York's Elise Stefanik, who is 31 and a millennial herself, likely won't change the overall image of the Republican party in the eyes of young voters.

"I haven't seen any evidence that indicates a significant change" in millennial voter preference patterns, Rohde, of Duke University, said. "I don't think we're seeing a shift so much of young people to the Republicans, but we are seeing a disproportionately low likely chance to participate."

If you made a list of some of the major issues dividing Congress and compared Ryan’s position to that of Pelosi – a Democratic congresswoman from California 30 years his senior – you would likely find younger voters don’t much care how many wrinkles their representatives have, said Joel Aberbach, a professor of political science at the University of California Los Angeles.

“It’s an irony,” Aberbach said, referring to the Pelosi-Ryan dynamic. “[I think] she’d end up more in sync with young people than I think [Ryan] would right now.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.