Why Are Americans Moving Less? Will It Hurt The US Job Market And The US Economy?

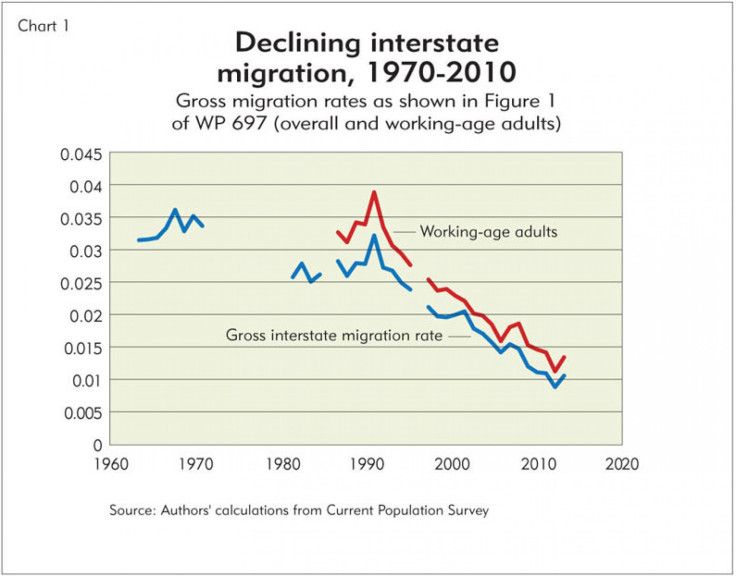

Americans have traditionally been among the world’s most mobile people. But for at least the past two decades, the rate of migration among states has been falling steadily and is now only about half of what it was in the early 1990s.

In a market economy, labor mobility is a factor that mitigates the effect of economic shocks. A high level of mobility allows the U.S. economy to respond flexibly to local shocks, such as the recent oil boom in North Dakota, and suggests that American workers will go wherever they are most productive. With fewer people packing up and relocating, does this mean the U.S. labor market is losing flexibility? And will the economy suffer as a result?

According to the latest census data, one out of eight Americans moved in 2012. That’s up from the previous year’s record low, but still much lower than it used to be. Between the 1960s and the early 1980s, about one in five Americans moved each year. Among last year’s 11.8 million intercounty movers -- people who moved to another county, either within the same state or to a different state — the most common distance moved was less than 50 miles. In other words, even though they moved to a different county, most did not move far from their previous place of residence.

Researchers have suggested many possible explanations for this shift. Perhaps it’s because America is aging, and the elderly prefer to stay put. Or perhaps there’s a rising share of dual-earner households. When both spouses are employed, it can be more difficult to move long distances because both people must find a suitable job in the new location. More recently, the poor economy and the housing bust might also have played a role. After all, it’s hard to move when your house is underwater.

In a paper published in 2011, UCLA economist Hernan Winkler examined the effect of homeownership on mobility and labor income and concluded that owning a home makes workers less likely to move in response to labor market shocks. Winkler also found that homeowners suffering from a decrease in home equity are 40 percent less mobile.

Princeton sociologist Katherine Newman pointed out in a 2010 New York Times article that people are more likely to stay near friends and family during recessions to help them get through hard times. “Staying put may mean that we retain the strength of our ties to one another,” Newman wrote.

Economists at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors discovered a strong correlation between the decline in interstate migration over the long term and the drop in how frequently people change jobs. In other words, Americans are moving less because they are changing jobs less.

According to calculations by economists Raven Molloy and Christopher Smith of the Federal Reserve and Abigail Wozniak of the University of Notre Dame, the interstate migration rate in 2011 was 53 percent below its 1948-1971 average, while the rates of moving between counties within the same state and of moving within the same county fell 44 and 36 percent, respectively, over the same period.

The authors found that demographics can't explain the drop, since Americans of all ages and groups are moving less. They argue that the drop is related to a drop in the number of workers switching jobs, industry or occupation.

Last year, 53 percent of adults held the same job for at least five years, up from 46 percent in 1996, according to the Labor Department. Only 16.1 percent of workers left their jobs voluntarily in 2009, down from 25.2 percent in 2006.

The graph shows a very strong positive correlation: States like Florida and Texas that experienced very large drops in the fraction of workers who changed firms also experienced the largest decreases in in-migration.

In a February 2013 working paper, entitled “Understanding the Long-Run Decline in Interstate Migration,” economists Greg Kaplan and Sam Schulhofer-Wohl argue that neither demographics nor the recession can explain the drop in mobility. For instance, the decline in migration is most pronounced among the young, not the old.

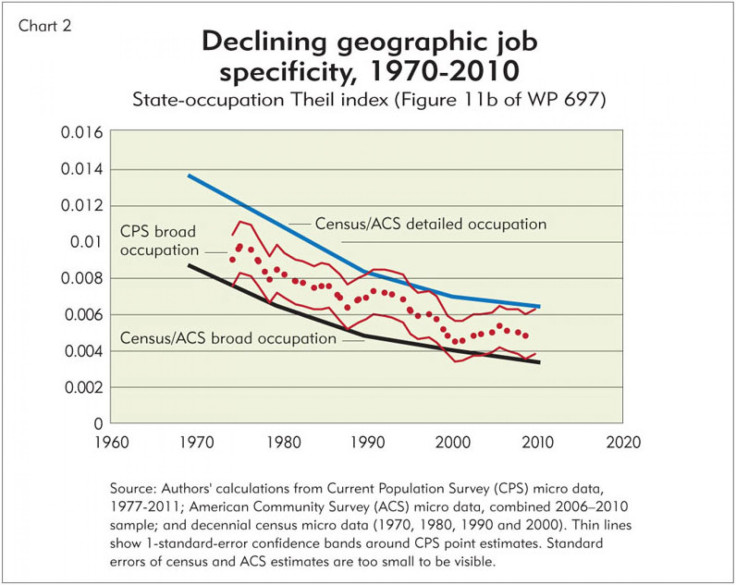

Their theory is that the financial benefit of switching jobs is less than in the past — the wage increase that historically came with switching companies has declined over time. Americans are moving less because they don’t need to move as much. Jobs in the U.S. are no longer quite as geography-specific as they used to be.

The chart below illustrates this decrease in the “geographic specificity of occupations” with a statistic called the Theil index. It shows that the mix of available jobs differs less from state to state than it did 20 years ago, and the income a worker can earn in a particular occupation depends less than before on what state he or she works in.

Kaplan and Schulhofer-Wohl said that their explanations account for at least one third, if not all, of the decline in interstate migration.

If they’re right, then the fact that Americans aren’t moving around as much anymore isn’t necessarily something to worry about. “In other words, American workers haven’t lost their flexibility. They just don’t need to move so much anymore,” they concluded.

Moreover, when we put it in an international context, the U.S. is still one of the most mobile countries in the world:

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.