Why Are Drugs So Expensive? One Reason: Scientists Can't Reproduce Each Other's Work

Dr. Moshe Pritsker ran up against one of the most aggravating problems in science as he embarked on his doctoral research in molecular biology at Princeton University. He was trying to reproduce an experiment on embryonic stem cells that he had read about in a journal. But no matter how hard he tried, he could not replicate the original experiment’s findings.

After several colleagues also came up short, he hopped on a flight and spent two weeks working alongside the scientist who completed the original work. There in the lab, Pritsker was able to witness the researcher's methods firsthand and eventually learned enough to replicate the findings, but he was left feeling frustrated by what the ordeal meant for his field.

“The whole premise of science is that it's reproducible,” he says. “Science is not a science if it's not reproducible.”

It’s an unglamorous truth of scientific inquiry -- researchers consistently fail to reproduce each other’s experiments. While any scientist should, in theory, be able to replicate the findings of another based on the scientific method, the reality is that most results are not nearly so reliable. Their frequent failures slow the pace of innovation and ultimately cost researchers at universities, government agencies and companies time and money.

Pharmaceutical companies in particular are worried that this challenge will continue to push their costs, and therefore prices, to ever-higher levels. Drug research has grown increasingly less efficient in recent decades and Dr. Ulo Palm, chairman of the research committee for food and drugs at the American Society for Quality, suggests that a lack of reproducibility is at least partly to blame. The number of Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs the pharmaceutical industry pumps out for every billion dollars it spends on research and development has dropped by 50 percent every nine years since the 1950s in a trend known as Eroom’s Law. Today, it costs $2.6 billion to usher the average drug to market, which is more than double the cost from a decade ago, according to a recent analysis from the Center for the Study of Drug Development at Tufts University.

Meanwhile, the amount of medical literature generated by researchers in the field is doubling every five years.

“We know so much about modern biology but somehow, we don't seem to be able to turn it into real treatments because our resources are wasted on trying to reproduce work that is faulty in the first place,” Palm says.

Starting in 2002, scientists at Amgen tried to replicate 53 landmark scientific studies. A decade later, they published a paper noting they could only confirm the findings of six. Researchers at Bayer run up against this problem in roughly two-thirds of the studies that they try to validate when seeking new treatments for cancer and cardiovascular disease.

“If you look at what’s happened to human health over the last couple of decades, researchers have made enormous improvements -- that's not in dispute,” C. Glenn Begley, a former Amgen scientist who published a record of the company’s attempts to replicate landmark research, says. “What's concerning to me is that we could have made so much more progress. It’s that opportunity cost that is frankly impossible to quantify.”

Palm has also confronted the issue himself. In the mid-1980s, he failed to replicate an experiment having to do with kidney physiology during his doctoral research and later, while working for Novartis, he assumed responsibility for controlling the quality of the in-house experiments and improving the rate of reproducibility -- a position created to make research spending more efficient.

Sometimes, scientists' failures to reproduce earlier findings come as the result of fraud or misconduct on the part of the original researchers -- as in the case of a young Japanese researcher who was found guilty of misconduct after others couldn’t replicate a technique she claimed to have found for creating stem cells last year. But such cases are rare. More often, scientists fail to duplicate results because they don’t understand how the first experiment was done or due to the complications of bias, or because an honest mistake was made in the original work.

The issue prompted editors from 30 of the top biomedical research journals to pledge last summer to pack more experimental details into each paper, encourage scientists to upload their raw data to open access sites and publish more refutations of existing research, which have long been shunned from their pages.

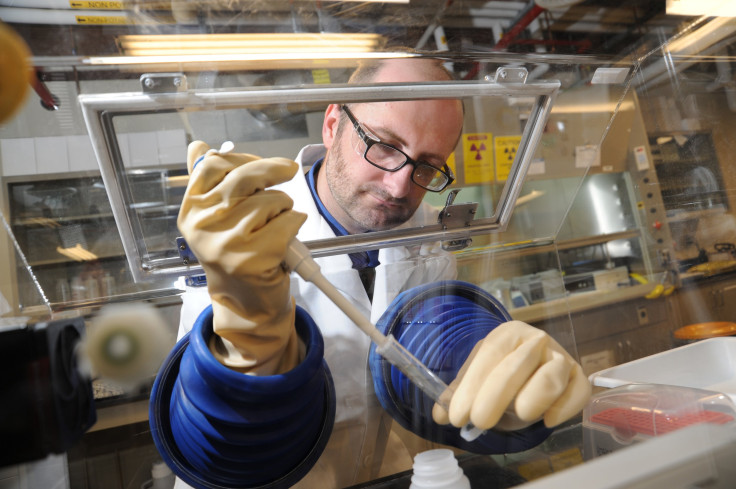

These new guidelines will help but Pritsker, who struggled to reproduce experiments as a doctoral student, believes that many such failures are a result of poor communication between scientists about their methods. That’s why he started the world’s first peer-reviewed video journal in 2006 called the Journal of Visualized Experiments (JoVE). His crew films experiments across dozens of scientific disciplines and publishes them online, allowing scientists to closely follow along with every step.

The approach has worked well for Robert Flowers, a chemist at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, whose lab handles a reagent that is particularly difficult to make. Every month or so, a student in another lab would write to him and ask for details about his work. Flowers would often set up a Skype call to explain it but after publishing his process on JoVE, he receives far fewer requests. Flowers has since joined the company’s advisory board.

Several pharmaceutical companies subscribe to JoVE and so do nearly 800 institutions including Harvard University, Cornell University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A client at the University of Washington said her lab saved $40,000 by watching experiments rather than hiring an extra hand that would have otherwise been needed to conduct all the trials they've avoided. Jeannette Moore, a lab manager at the University of Alaska Fairbanks said the service helped her lab cut back training time for new students by six months.

Pritsker’s concept does have its limits, though -- it costs JoVE about $10,000 to publish a video while he says the cost to editors of publishing an article in a traditional scientific journal is $1,000 to $3,000. Others have also launched more affordable approaches to improve scientific communications -- a nonprofit called the Center for Open Science is encouraging scientists to share data throughout the course of their experiment while PsychFileDrawer logs the successes and failures of experimental psychologists, who work in a field where bias looms particularly large, to validate one another’s results.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.