Why Declaring Monkeypox A Global Health Emergency Is A Preventative Step – Not A Reason For Panic

Countries that are members of the United Nations are obligated to report cases of unusual diseases that have the potential to become global health threats. In May 2022, more than a dozen countries in Europe, the Americas and other regions of the world that had never before had cases of monkeypox started to report cases occurring within their borders.

In response, the director-general of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, convened a monkeypox emergency committee to track the evolving situation. At the committee’s first meeting on June 23, 2022, the members observed that the “multi-country outbreak” might be stabilizing as case counts had plateaued in several countries.

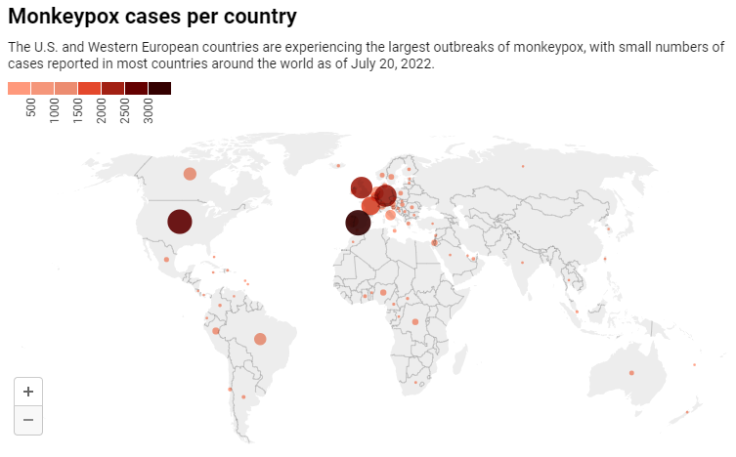

However, after thousands more cases of monkeypox were diagnosed in dozens of countries in July, it became clear that the outbreak had not stagnated. On July 23, 2022, Tedros declared monkeypox a public health emergency of international concern.

As a global health expert who specializes in infectious disease epidemiology I do not think that most people need to be worried about monkeypox. This decision by the WHO, though it may sound ominous, is not a sign of bad things to come. Rather, it is a way to prevent monkeypox from becoming a global crisis.

What is a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC)?

The International Health Regulations are a set of rules that guide how the WHO and United Nations member states respond to emerging health threats.

Under the current regulations, a “public health emergency of international concern” – often abbreviated as a PHEIC – can be declared by the WHO director-general when three criteria are met: the situation is an “extraordinary event,” there is a risk of spread to other countries, and the situation might “potentially require a coordinated international response.”

Before monkeypox, only five diseases had been designated as PHEICs since the WHO started using the term in 2005: the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009; polio resurgences in Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan in 2014; the Ebola epidemic in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2014 and an Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo 2019; the spread of Zika virus in the Americas in 2016; and the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. While all of these events were noteworthy, only the coronavirus pandemic became a worldwide catastrophe.

Why is monkeypox a public health emergency of international concern?

The director-general of the WHO is the only person who can declare a PHEIC, but the decision is based on advice from the designated emergency committee. After the monkeypox emergency committee met for the second time, on July 21, 2022, it released a report stating that “the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox meets all the three criteria defining a PHEIC.”

The rapid spread of the virus to more than 70 countries was evidence of the risk of further international spread. The committee expressed concerns about whether vaccines would be priced reasonably and distributed equitably in the absence of a coordinated international response. And it agreed that there were aspects of the situation that were “extraordinary” – a vague term that is not defined in the International Health Regulations.

However, the committee did not express unanimous agreement that a public health emergency of international concern should be declared. Some members questioned whether a disease that has a low case fatality rate should be a PHEIC. Others worried that a PHEIC designation could further stigmatize LGBTQ communities since most cases thus far have been diagnosed among men who have sex with men.

The vote from the emergency committee was split – nine against and six for PHEIC status. But Director-General Tedros opted to go ahead and declare monkeypox a PHEIC.

What happens now?

The goal of a PHEIC designation is to prevent an emerging disease from becoming a global health crisis. The WHO has two initial goals for monkeypox. First, to try to stop the virus from beginning to circulate in susceptible populations where it is not currently present. And second, to distribute vaccines and antiviral medications to the countries and communities that need them most.

After the PHEIC declaration, the WHO released a set of temporary recommendations that asks countries to work harder on preventing cases in affected and at-risk communities, to improve clinical care for people with monkeypox and to contribute to research on vaccines and treatments for monkeypox. The recommendations also ask countries to advise infected individuals and their direct contacts not to travel except in urgent situations, but they do not impose any restrictions on international travel or trade.

Finally, the WHO has advised that individuals who are members of at-risk communities take steps to protect themselves from the virus, but has not called for changed behavior in the general public.

A public health emergency of international concern is the highest level of alert in the International Health Regulations, but it is not a synonym for a pandemic. The status is a tool for protecting global population health and not a declaration that a global crisis is already happening.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

Kathryn H. Jacobsen is a William E. Cooper distinguished university chair and professor of health studies at the University of Richmond.