Why Do Prescription Drugs Have Such Weird Names? Blame Branding Consultants And The FDA

Imagine going to the pharmacy to fill a prescription that your doctor said would relieve a throbbing elbow, and instead, the clerk hands you an antidepressant. If drugs like Celebrex, which is used to treat arthritis, and Celexa, an antidepressant, look and sound too much alike, pharmacists and nurses can easily confuse a doctor’s orders. The Food and Drug Administration is increasingly wary of this danger, making it harder than ever for pharmaceutical companies and branding experts to dream up a name that the agency will approve.

The heightening challenge explains why prescription drugs notoriously carry some of the most obscure brand names in business. In recent weeks, the FDA approved Celecoxib, Linezolid and Metaxalone -- names that don't exactly roll off the tongue. But despite their irregular appearance, there's a logic to the process. Drug names often contain subtle linguistic cues that are the product of a high-stakes creative exercise that marries the magic of marketing with consumer psychology and scientific testing.

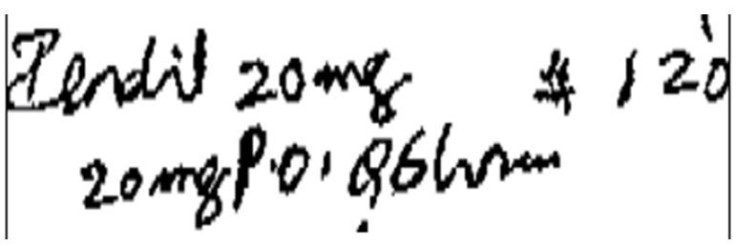

Developing brand names for medicines is a careful dance between marketing experts and scrutinizers at the FDA, who reject about four out of 10 proposed brand names for new drugs. From the FDA’s point of view, it’s important for a new drug to have a clear name that can’t easily be confused with others. Patients can wind up taking the wrong prescription if a pharmacist mistakes Foradil, which treats bronchitis, for Toradol, which relieves pain from arthritis, or mixes up the blood-thinner Plavix with the antidepressant Paxil.

About 15 years ago, the FDA began to realize that pharmacists and doctors were confusing medicines such as Celebrex and Celexa -- not to mention the fact that both drugs' names sound a bit like Cerebyx, which is used to treat epilepsy. There were 126,000 cases of medication error between 2000 and 2009 in the U.S. and 8 to 25 percent of those errors were said to be caused by drugs sounding too much alike. Roughly 10,000 patients were injured per year as a result.

This confusion became such a concern that in 2001, the FDA required manufacturers of 16 medications that looked or sounded similar to begin writing their generic names using capital letters to make their most unique parts stand out. So Clomiphene became ClomiPHENE and Clomipramine became ClomiPRAMINE. This was an imperfect fix, however, and the agency has since created a strict review process to catch potentially confusing names before they are approved in the first place.

Eliminating confusion may seem like a straightforward request, but finding a new name has become increasingly complex and expensive for pharmaceutical companies as more and more drugs get approved. Many companies that used to complete this exercise in-house now hire consultants and branding experts to find one. The entire process may cost companies between $250,000 to $500,000.

“Every name that you could possibly make up is kind of close to something out there,” says Maury Tepper, a trademark lawyer at the law firm Tepper & Eyster in Raleigh, North Carolina, who has worked with many companies on naming medications. “It's just really hard to thread the needle, so we have to make a lot of hard decisions about how close is too close?”

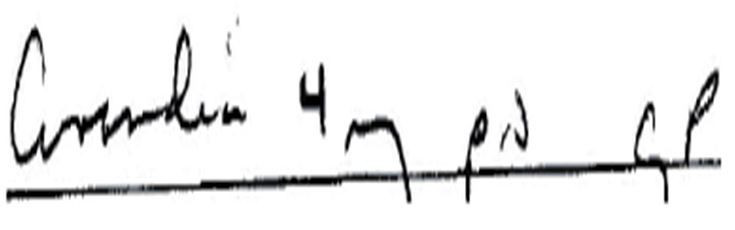

The FDA’s Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis compares and contrasts the way drug names appear when written by hand to make sure an “i” that turns into an “l” or an “a” which becomes an “o” can’t fundamentally alter the meaning of the prescription. The agency even pays nurses, pharmacists and doctors to act out simulations to see whether a new drug name is likely to be mistaken for any other in discussion or while writing prescriptions. Pharmaceutical companies run all these same tests before submitting a new drug name to the FDA to improve their chances of earning approval.

“When I started in this space, it was an art -- it was creative,” says Brannon Cashion. He is the president of Addison Whitney, a firm headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina, that has helped to name hundreds of drugs for a long list of clients including Merck, Pfizer, Bayer and AstraZeneca, says. “Now it really is a science. What are the overused prefixes and suffixes? What are the guidelines and rules across the globe?”

But finding a word with a clear meaning is only the first hurdle -- the FDA’s Division of Drug Marketing, Advertising and Communications also rejects drug names that are “overly fanciful,” which is the main reason companies stick to neutral names such as Nexium for heartburn rather than, say, Digest-A-Whiz. A drug name that implies an effect that the medicine doesn’t have, leads patients to believe a medicine works for more conditions than for which it is approved, plays down a drug’s risks or suggests superiority over another project would be denied on these grounds.

“All these drug names -- they mean nothing, they're all coined words or invented words,” Cashion says. "What makes a good name is -- it is easy to pronounce, it is easy to remember and does it have a neutral to positive impression on your target audience?"

At the same time, pharmaceutical companies do want to find names that seem familiar and accessible to consumers. That leaves marketers such as Cashion and Suzanne Martinez, senior identity consultant at the health care brand consultanting group InterbrandHealth, to find ways to make medicines stand out with language that has largely been weaned of any obvious connotations.

Martinez says many drug names manage to slip in subtle signs-- such as Concerta for ADHD which sounds an awful lot like “concentrate.” Lipitor helps to lower cholesterol and cholesterol is a type of lipid, or fat. Early TV ads for Celebrex which treats arthritis encouraged consumers to “celebrate Celebrex.” Tepper points out others – Relenza provides “relief from influenza” and Tamiflu might “tame the flu.” Sometimes, even the experts are incredulous that other companies have managed to earn approval for such flagrant violations of the FDA’s policy.

"I look at them all the time and say, 'Wow, how did they get that name approved?'" Martinez says. "The one that has always irked me was Vimovo which to me says, vitality and moving. It's a pain reliever." Martinez says this tendency becomes most obvious when entire categories of medicines are named in a similar way, and her firm taps into these trends depending on a client's preference.

“If it's a cancer drug, oftentimes we want it to be a much stronger and powerful name,” she says. “Birth control is a category where the names sound quite feminine and soft and have this poetic feel to them.” Soft, rounded letters such as “a” can make a drug name “sound elegant,” she says – a new drug to treat low sex drive in women, for example, will be sold as Addyi.

Tepper is wary of names that try too hard to imply an effect, because they flirt with the FDA’s tolerance for such antics. He prefers names which act like “empty vessels” that can be filled with meaning for a patient through marketing campaigns and their own positive experience with a medicine.

“It's a bit like cooking -- a dash of it is a good thing, but too much of it can ruin the dish,” he says.

Cashion’s firm, which he estimates has a hand in shaping about 35 percent of the brand names that are approved by the FDA each year for prescription medicines, pays careful attention to how memorable a name will be and looks for nontraditional letter strings or unusual consonant-vowel structures such as those in Qvar and Vfend.

“Memorability is really big in the drug world,” he says. He thinks a short name is often easier for patients to remember than a long name, and sounds punchier when pronounced. Many medicines have an “x” and “z” because these letters once helped them to stand out, though lately Cashion has started to notice more “k’s” and “j’s” instead.

The experts at InterbrandHealth use similar methods to imply that a drug is very special, or communicate friendliness or technical expertise. Sometimes Martinez will speak with scientists about how a drug works and hint at an original mechanism through a particular series of letters.

“If we have permission to create a very new-looking name for an innovative drug and want to signal to the market that it's breakthrough science, you can do that by creating a brand new name that doesn't communicate anything -- it just looks new,” she says.

Her group also interviews potential patients to learn about how they interact with a medicine in their daily lives – when they take it, where they take it and how they feel about their condition.

“If a name looks very technical, it may be scary,” she says. “If people are already feeling a little fearful given whatever they're coping with, we don't want to add to that.”

At the end of the day, companies may submit up to two potential names to the FDA for consideration. Tepper says these names have usually been whittled from a list of 300 to 500. Cashion says the entire process from the first brainstorming session to approval can take anywhere between 18 to 24 months. Overall, the FDA reviews more than 500 proposed names for new medicines each year.

Occasionally, a medicine with a too-similar name slips through even after careful review. While it’s possible to change the name of a medicine after it launches, no company wants to absorb the huge expense of updating labeling and marketing or endure the headache of re-educating doctors and patients. Cashion helped Takeda Pharmaceuticals switch the name of a drug known as Kapidex to treat heartburn in 2010 because it was too easily confused with a drug called Casodex which treats prostate cancer by inhibiting the male hormone testosterone.

So has all of this attention by the FDA and painstaking research by pharmaceutical companies lessened the number of medication errors caused by too-similar drug names? Unfortunately, Tepper points out that even the clearest drug name can still be garbled by a doctor with poor handwriting. Only about half the states require doctors to type up a prescription rather than write it out by hand.

“We don't really have any evidence to show that we've moved the needle very much,” he says. “I'd love to say that we have.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.