Why It’s No Surprise Mexico Could Soon Surpass Japan To Become The No. 2 New-Auto Exporter To The U.S.

Mexico is almost there, at least when it comes to building cars.

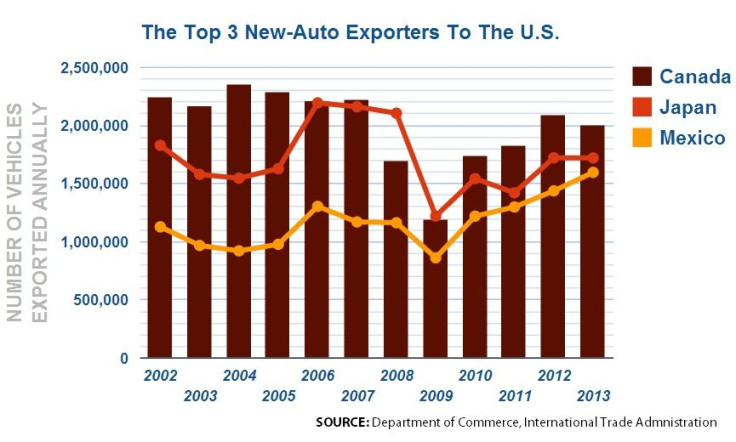

Twenty years after the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the third-largest trading partner to the United States (after Canada and China) could surpass Japan as the second-biggest exporter of new passenger cars and light trucks to the U.S. after Canada. The shift would make sense since NAFTA has made the country an appealing place to assemble goods for the wealthy U.S. market.

The automotive unit of global industry data-analysis firm IHS Inc. sees Mexico brushing past Japan this year by about 200,000 vehicles, to approximately 1.7 million. Full-year figures released Friday by the Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration show the two countries neck and neck.

Japan exported about 124,000 more vehicles than Mexico. The last time the two countries were so close in exports was in 2011, when the spread between the two was about 122,000 units.

What’s going on? Mexico doesn’t have any homegrown automotive manufacturers, while Japan is home to four of the world’s top 10 auto companies, the world’s largest Toyota.

The answer of course is NAFTA, which lowered barriers that allowed manufacturers to set up shop in Mexico and export assembled autos that often use parts manufactured in Mexico’s two trading partners up north. Under free-trade rules, manufactures only pay tariffs on the added value of assembling imported components to make the final product in Mexico. Exports are now valued at about $71 billion, according to the Mexican Automotive Industry Association. Mexico now manufactures nearly one out of every five North American-built passenger cars, an almost three-fold increase since NAFTA went into effect on Jan. 1, 1994.

In other words, Mexico trades revenue on charging import duties of auto parts used to make cars that will be exported, and in exchange, companies set up factories there that create jobs and economic activity that Mexico’s free-trade proponents and politicians can point to. As in the U.S., Mexican states compete for this auto factory work, offering tax breaks, infrastructure investments and other incentives.

Mexico’s proximity to the U.S., the world’s second-largest auto market after China, makes it an ideal location, especially in the country’s heartland, which is well connected to the U.S. via modern highways. Mexican autoworkers also have far less collective-bargaining power than their counterparts in Europe, the U.S., Canada and Japan. By most estimates, they earn about $2 an hour on average, a fraction of what even a nonunion autoworker in the U.S. makes.

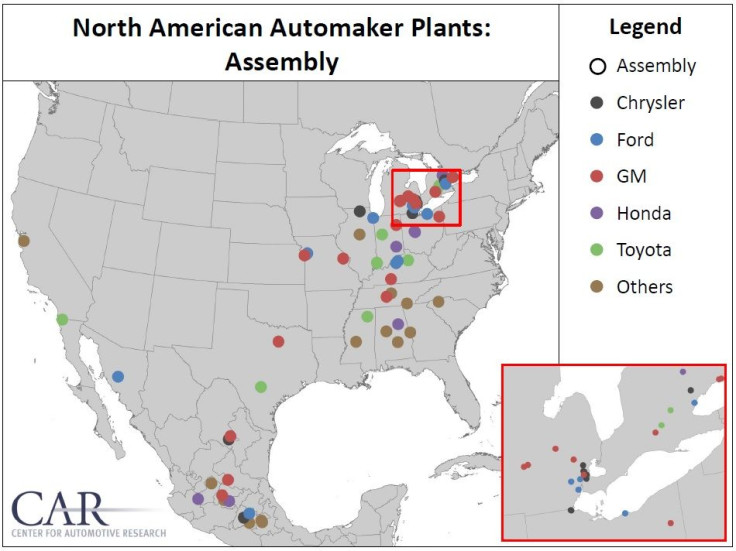

Since NAFTA, there has been an influx of factories into Mexico. Honda opened its first Mexican assembly plant in the state of Jalisco in 1995, a year after NAFTA went into effect, and the 2015 Honda Fit is starting to be produced in Guanajuato at the company’s new $800-million assembly plant. Toyota made its first foray into Mexico in 2002, when it opened up shop in Tijuana, just south of the border, to assemble the Tacoma pickup truck. The Big Three automakers in Detroit have made similar investments in the country, which had 15 manufacturing facilities assembling vehicles for several automakers as of 2012, according to the Center for Automotive Research in Detroit. Recently both Mazda and Nissan have set up shop in Guanajuato and Aguascalientes.

NAFTA has clearly helped the auto industry become a major economic force in the country – it’s now a greater source of state revenue than oil exports and remittances from migrants abroad – poverty continues to increase even as household incomes rise.

Current World Bank figures show the number of people in Mexico who have fallen below the poverty line has increased from 47 percent of the population to 52.3 percent, from 2005 to 2012, even as per capita income has also increased, from $7,710 to $9,640 in the same period of time. This suggests that free trade has greatly benefitted many households but not enough to resolve Mexico’s persistent poverty problem.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.