Why Meeting With Putin May Just Give Trump A Popularity Boost

By setting a summit with Vladimir Putin, President Donald Trump is hoping to smooth over bad relations between the United States and Russia. He may also be thinking about benefiting in the polls and at the ballot box.

As a scholar who looks at how bellicose actions can boost presidential popularity, I started to wonder if peace also paid a dividend for presidents – maybe even a bigger one than waging war or talking tough.

Peace is at hand – elections, too

“Peace is at hand.” These words – spoken at a Washington, D.C. press conference on Oct. 26, 1972, by National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger about the status of the Paris Peace Conference negotiations with North Vietnam – are said to have sealed the re-election bid of Richard Nixon.

Two weeks later, Nixon won 61 percent of the popular vote against George McGovern, along with 49 of 50 states.

And yet, it is the diversionary theory of war that is well-established in the field of international relations. Based on theories of conflict by Georg Simmel and Lewis Coser, scholars contend that when a leader is facing internal trouble, fighting an external foe can provide a “rally ‘round the flag” effect from a burst of patriotism that accompanies war. Sometimes it’s even possible to make a foreign rival the scapegoat for a mess at home.

The theory crossed over from professors to pundits in 1998 when Bill Clinton launched missiles against al-Qaida targets in the Sudan and Afghanistan in retaliation for attacks on U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Clinton was plagued by the Monica Lewinsky scandal at the time and reporters linked the bombings to the 1997 film “Wag the Dog” about a president who wages a fictitious war to cover up a sex scandal.

While the media began to apply the theory to nearly every use of force, many scholars tried and failed to find strong corroborating evidence that leaders started conflicts as a diversion. Some found more evidence that conflicts short of war, like verbal threats, were used as diversions in U.S. foreign policy.

Other scholars looked abroad and were able to associate threats and limited displays of force with leaders facing domestic troubles, especially in the Middle East.

Distracting the public with peace

So while picking fights overseas as a way of drawing a nation together may not be as common as we think, could peace be a better political strategy?

Scholars analyzing the Democratic Peace Theory argue that when given the chance, people vote for peace. Authoritarian regimes are the ones who drag the public into bloody conflicts. But this theory has no shortage of critics. Political scientist Barbara Yoxon notes that there has been a recent rise in the number of phantom democracies that combine elements of democracy and autocracy, hosting elections that are often unfair, and fail to deliver basic freedoms to the people. But true democracies rarely go to war because the government is responsive to the people, who want peace.

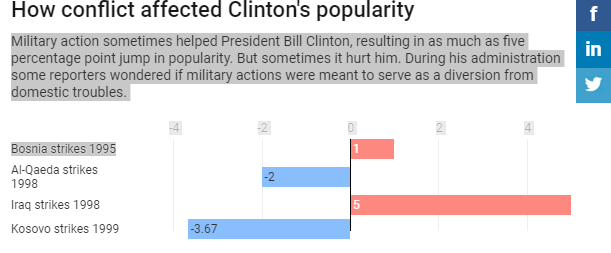

Democratic President Bill Clinton achieved a bump in only one of his four major uses of force during his administration – a five-point boost when targeting Saddam Hussein’s facilities in Iraq that were rumored to house a weapons of mass destruction program. Bombing Bosnia netted a one-point increase on average while Clinton’s approval ratings fell by more than three points after a Kosovo bombing and two points after targeting al-Qaida.

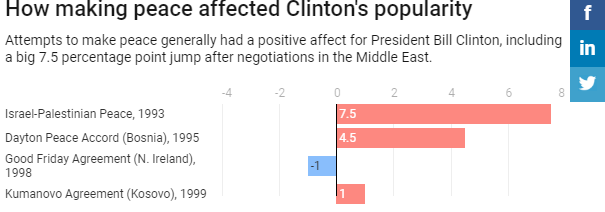

Sure enough, peace paid off better for Clinton in the polls. As he brought Israel’s Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat together for a historic handshake, Clinton’s approval rating jumped up 10 points in one poll, with an average approval rating increase of more than seven points. The Dayton Peace Accords that terminated hostilities in Bosniagenerated a 4.5 percentage point jump. The deal that ended the Kosovo conflict, the Kumanovo Agreement in Macedonia led to a slight increase. The exception was a slight dip in polling following the Good Friday Agreement in North Ireland which the U.S. helped negotiate. All of the Clinton polling averages were taken from Gallup.

North Korea and Russia

Shortly before President Trump launched his peace initiative in North Korea, he was sitting at a 40.25 percent average in the polls. That climbed to 44 percent over the two days the story first broke. The effect only lasted a few days, but those polls crept up as the Singapore summit approached, culminating in an average of nearly 45 percent according to RealClearPolitics’ polls of Trump’s approval ratings. Some surveys indicated support at 49 percent before the furor over the detention of immigrant children brought those numbers back down.

Contrast this with results from Trump’s threats against Kim Jong Un. After his “fire and fury” verbal assault on Aug. 8, 2017, Trump dropped from an average approval rating of 37.7 percent to 36.7 percent. It was a similar story on Jan. 2, 2018, when Trump bragged about “the size of his button.” Then, he slid from a pre-poll average of 41.3 percent to 39.9 percent.

Both uses of force against Syria over chemical weapons met with a tepid response at best. Before and after the Shayrat base strike on April 6 to 7, 2017, Trump’s average fell from 40.7 percent to 40 percent. Nearly a year later, the second use of cruise missiles in Syria changed nothing about Trump’s standing in America, stuck at 40 percent. Gallup polling showed the same results.

Is peace a sleight of hand?

So should we expect that meeting with Putin will make Trump more popular?

That may depend on whether the public believes the diplomacy was designed for a true reconciliation of hostilities – or merely a ploy to win re-election, help his party in the midterms, or cement his legacy in the history books.

After all, peace wasn’t really at hand before the 1972 election, as talks broke down and the bombing of Vietnam resumed, a conflict to be decided at a later date, when polls didn’t matter as much.

John A. Tures is a Professor of Political Science at Lagrange College.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article here.