Why Next Two Years Are Critical For The Paris Climate Deal’s Survival

A mounting sense of urgency will greet negotiators as they arrive at this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference in Poland. In 2015, after 20 years of trying and failing to reach a global accord on climate-changing emissions, 195 nations hammered out a deal, the Paris Agreement, that all of them could accept.

Three years on, it’s becoming increasingly clear that national decisions about climate action, which country negotiators will convey in Poland and over the next two years, will determine whether the breakthrough Paris pact succeeds both on a political and emissions reduction front.

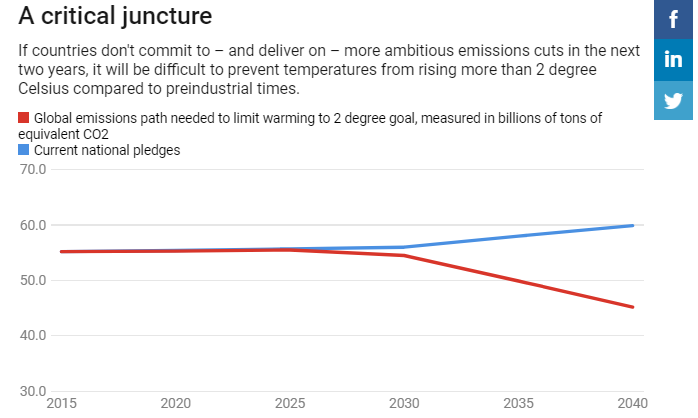

As scholars at the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, we have closely followed the global climate change agreements and studied their implications. Based on our analysis of nations’ commitments to cut emissions, getting the world on track to achieve the agreement’s signature goal – to keep global warming below two degrees Celsius – will require far more ambitious climate action than what countries have pledged so far. This action must begin sooner rather than later to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, from severe droughts to extreme flooding.

Climate change won’t wait for humanity’s response

Climate change is the type of problem where delay is especially costly. It is not like other pollution such as dirty urban air or a putrid stream. For these, people might clean up a polluted area this year, but if they put off the task, there will probably still be the same opportunity to get it done the following year.

Not so with greenhouse gases, which hang around for decades to centuries. So if societies delay revising our current practices – burning fossil fuels, chopping down forests, planting more polluting crops like rice, as well as raising cows – the total amount in the atmosphere will grow. The goals for limiting global warming will get steadily more difficult to achieve.

In addition, as the nations’ representatives gather in Poland to pursue their effort to gain control of this process, a crucial decision point is rapidly approaching.

Brutal timing

In the Paris Agreement, each nation is to make a pledge (what the agreement calls a Nationally Determined Contribution) to achieve a level of emissions control by a target date. For most countries this is the year 2030. They will also submit to a review of whether they did what they said they would do every two years.

Our analysis shows that, fortunately, meeting these Paris pledges will halt emissions growth at least to 2030, though without additional action growth will resume thereafter. This voluntary system of pledge and review represents real progress on this difficult issue. Experts in international affairs argue that it is perhaps the best deal possible for a 195-nation agreement.

The pledges for 2030 are just the first step, however. Getting the globe onto a path to the 2°C Paris goal, much less to meet its stretch objective of 1.5°C, will require stronger action beyond 2030.

How tough the emissions restrictions must be in the next decade or two depends on the pace of reduction that may be feasible later in the century – and here emerging technology could possibly play a role. For example, a significant effort is underway to develop techniques to suck carbon dioxide (CO2) out of the air and store it underground. If we could count on this option becoming available and affordable in the future, participating nations in the Paris Agreement could relax their emissions controls a bit now and the temperature goal could potentially still be met.

We take the view, however, that it is not wise to bet the planet on the chance of a late-century technical fix. To avoid this risky bet, our analysis shows that meeting the Paris 2°C goal requires a dramatic turnaround in emissions in the very near future.

Why 2020 is a crucial date

The Paris Agreement sets up a five-year cycle of updates and specifies that in 2020 nations should revise their pledges for 2030, increasing ambition if possible. Also in 2020, nations are to pledge emissions reductions to be made by the next target date, likely to be 2035.

Whether there is financial aid for less-wealthy countries could have a big effect on the outcome. For 2030, and likely for future target dates, the pledges of many developing nations assume aid will be provided to help with the task. The richer countries have agreed to provide it, but the flow of funds thus far has been small in relation to the need.

This assistance will be increasingly important in the future because a growing share of global emissions will come from rapidly growing developing countries. We project these countries to represent over three-quarters of global emissions by 2030, and to continue to grow after that.

Failure to achieve substantial increases in ambition in these 2020 declarations, and the financial assistance to support them, would be bad news for the climate. Delay in starting the turn-down of emissions suggested in our analysis will further add to the collection of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. As their concentration grows, the path of reduction leading to a 2°C outcome will become steeper, and thus more costly, potentially putting temperature goals out of reach.

All this means that a wimpy response by participating nations in 2020 will threaten the credibility of the hard-won Paris Agreement. The willingness of nations to participate in such a volunteer control effort depends on confidence in the fairness and effectiveness of the global effort. Are others doing their part? Is the overall regime working? If countries don’t meet their Paris Agreement commitments to cut emissions and then, further, don’t ratchet up their ambitions, the entire agreement risks unraveling.

Time pressure

The current absence of the U.S. in global climate talks doesn’t help, but fortunately most other nations recognize the global risk and are making a serious effort to ensure that the agreement succeeds.

And all negotiators recognize that substantial new pledges in 2020 will help build confidence in the effort, besides encouraging everybody to make sure they meet their 2030 goals. There is great time pressure between now and 2020, given all that needs to be done. But this is nonetheless a time of great opportunity. Negotiated deals and national decisions made in these few months may determine whether or not the world’s nations will get on track to meeting this global challenge.

Henry D. Jacoby is a Professor of Management (Emeritus) and former Co-Director of the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, MIT Sloan School of Management. Jennifer Morris is a Research Scientist, Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the article here.