Why Trump May Usher In The Biggest Gas Tax Hike Ever

The White House aims to boost what the federal government spends on big public works projects by about US$200 billion over the next decade as a part of its plan to fix the nation’s ailing infrastructure. So far, it’s unclear how the Trump administration plans to pay for most of this spending surge at a time when revenue is about to fall due to massive tax cuts.

As the director of energy studies at the University of Florida’s Public Utility Research Center, I’ve studied both taxes on energy and how the government leverages what it spends on infastructure through public-private partnerships. I believe there’s a chance President Donald Trump will usher in the first federal gas tax increase in 25 years to cover the cost of new roads and bridges.

He has, after all, already said he supports a 25-cent-per-gallon increasethe U.S Chamber of Commerce is backing, even if that sounds hard to sell to his own political base and other conservatives.

To explain why the government may finally adjust the 18.4-cent-a-gallon tax, here’s a historical snapshot.

The First 40 Years

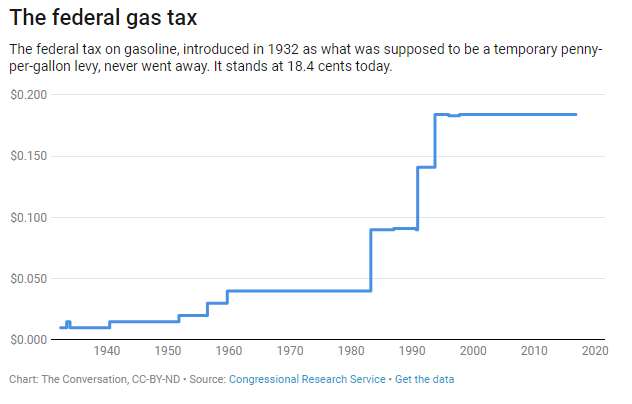

This resilient levy is a major source of U.S. funding for roads and transit today. It originated during the Great Depression as a “temporary” penny-per-gallon gasoline tax. At the time, a gallon cost about 18 cents, or $2.61 in 2015 dollars.

As he signed the Revenue Act of 1932 into law, President Herbert Hoover lauded “the willingness of our people to accept this added burden in these times in order impregnably to establish the credit of the federal government.”

The original gas tax, an emergency measure intended to bolster the budget and fund national defense spending, not meet transportation needs, was slated to expire in 1933. Instead, it remained in force throughout Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration over the objections of the oil, automotive and travel industries due to persistent budget deficits throughout the New Deal and World War II. It became a permanent 1.5-cent levy in 1941.

Multiple efforts to do away with the gas tax ever since have failed.

For example, Congress again scheduled the tax’s repeal in 1951 when it increased it to 2 cents as source of revenue related to the Korean War. Instead, lawmakers agreed to keep the tax on the books to help pay for one of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s top priorities, the national interstate highway system.

In 1956 the levy rose once more, to 3 cents, when Americans were paying about 30 cents for a gallon of gas. At the same time, the government established the Highway Trust Fund to pay for building and maintaining the new interstates.

The tax rose to 4 cents per gallon in 1959 and froze at that level for more than two decades.

Running On Empty

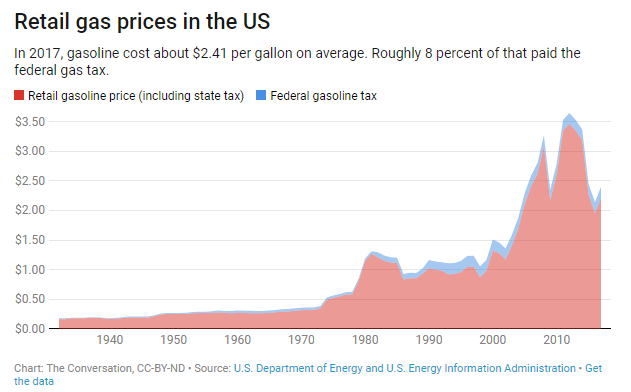

Gas tax revenue stopped keeping up with the expenses it was supposed to cover in the early 1970s following a severe bout of inflation and OPEC’s oil embargo. U.S. gas prices soared from about 36 cents per gallon in 1972 to $1.31 in 1981.

Responding to what members of both major political parties saw as a transportation infrastructure crisis, Congress more than doubled the tax to 9 cents per gallon as part of the Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1982. The same law split the Highway Trust Fund and its revenue stream into two parts: The first 8 cents would finance roadwork while the other penny would finance mass transit projects.

Nine cents may have struck drivers as a sharp increase, but public spending on transportation infrastructure would continue to fall as a percentage of all outlays.

In 1984, Congress increased spending on highways by funneling proceeds from fines and other penalties that businesses pay for safety violations, such as failing to label hazardous materials or forcing drivers to work too many hours in a row.

Congress boosted the tax twice more in the 1990s but primarily to reduce the then-ballooning federal deficit. Only half of a 5-cent increase in 1990 went to highways and transit, while a 4.3-cent lift three years later went entirely to lowering the deficit.

By 1997, the government had redirected all gas tax revenue reserved for deficit reduction to the Highway Trust Fund, where it still flows today.

Along the way, other federal fuel taxesarose, including a 24.4 cent-per-gallon diesel tax and taxes on methanol and compressed natural gas. And state fuel taxes, which in most cases began before the federal gas tax, range from as low as 8.95 cents per gallon in Alaska to as high as 57.6 cents per gallon in Pennsylvania.

Making Do

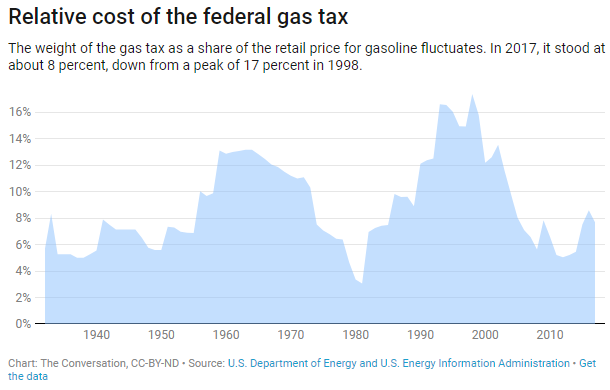

Since 1993, when the federal gas tax was first parked at 18.4 cents, inflation and rising construction costs have eroded its effectiveness as a transportation-related revenue source. In addition, U.S. vehicles have grown more fuel-efficient overall – which means Americans use less fuel for every mile they drive.

As a result, highway and transit spending have significantly outpaced the revenue collected from the gas tax and other sources. Since 2008, the government has spent $80 billion on highways that it had to take from other sources.

But it’s still not enough. The American Society of Civil Engineers, which gives U.S. infrastructure a D+, is calling on the government and private sector to increase spending on roads and bridges by at least $1 trillion within a decade.

Unusual Politics

Like the sharp gas tax increase during the Reagan administration, a 25-cent hike that Trump might sign into law would come at a time when the tax is relatively low as a percentage of the retail price of gasoline.

And like that early 1980s precedent, it would come at a politically surprising moment. Anti-tax conservatives were ascendant then. Now, Republicans, who say they believe in keeping taxes low, control the White House and Congress.

However, Trump has pledged to spend billions of federal dollars on new roads and bridges when there’s no money in the Highway Trust Fund for that. The money has to come from somewhere, and the Chamber of Commerce projects that raising the tax by a quarter could generate more than $375 billion in new revenue over a decade.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article.

Theodore J. Kury is the Director of Energy Studies, University of Florida.

<img src="https://counter.theconversation.com/content/92007/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-advanced" alt="The Conversation" width="1" height="1" />