Why Venezuela’s Oil Money Could Keep Undermining Its Economy And Democracy

As political and economic crises threaten to topple Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro, political scientists like us are not surprised that he has run into trouble.

Instead, we see Venezuela as another example of what scholars call the “resource curse.” That’s the unfortunate correlation first described by the British economic geographer Richard M. Auty between nations with vast wealth from oil or other natural resources and political instability.

Venezuela is a textbook case of the curse, since nearly 90 percent of its people are now living in poverty in the country with the world’s largest oil reserves. After decades of leaders who failed to harness this commodity for peace and prosperity, it is questionable whether a new government can do a better job.

Only a few oil- and natural gas-rich countries, such as the United States, Canada and Norway have avoided this curse – in part because they built solid institutions and diverse economies before their petroleum drilling began.

The resource curse

The resource curse has afflicted many Latin American countries with profligate and populist elected leaders who succumbed to the temptations of corruption and reckless spending when easy money poured in, followed by right-wing dictatorships imposing repressive technocracies. Oil and wealth from other commodities like gold and copper, and foreign aid, have also supported kleptocrats and dictatorships who have often used their fortunes to retain power in other regions.

The scholars Terry Karl and Thad Dunning have persuasively argued that oil export revenue helped sustain Venezuelan democracy from the 1950s to the early 1980s. The government, they explained, could buy support from the elite with lower taxes and from the poor with social programs.

Oil money, in short, can sustain whatever government is in power, be it dictatorship or democracy.

But when crude prices fall, the loss of revenue polarizes politics as the wealthy and the poor fight over the reduced proceeds. And when these countries not only rely on one export but also very limited markets, that adds to their vulnerability.

Oil sales constituted 98 percent of Venezuela’s export earnings in 2017, with the U.S. buying nearly half of the country’s exported crude.

Boom and bust

After several decades of strong economic performance backed by comparatively impressive social programs, Venezuela’s economy started to sputter in the 1980s. The vast sums of money it had borrowed a decade earlier, backed by future oil revenues, were coming due by that time.

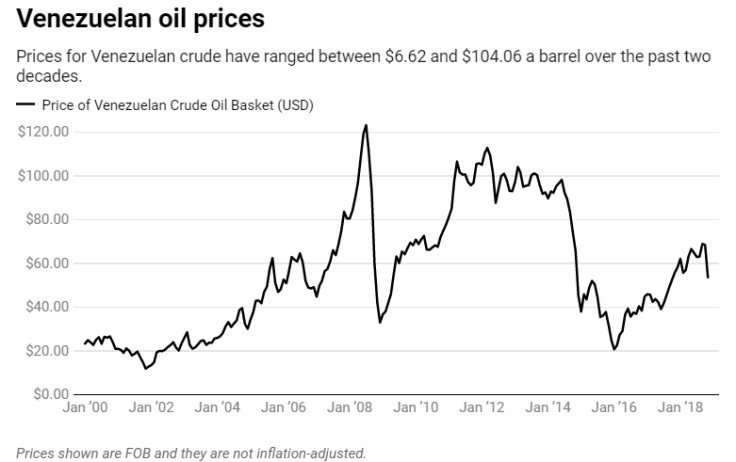

President Carlos Andrés Pérez, who had presided over strong economic growth between 1974 and 1979, returned to power in 1989. However, this time the country faced a weak currency, rising poverty rates, and increased foreign and public debt in combination with low oil prices.

To stabilize the economy, Pérez implemented austerity policies that deregulated capital markets and reduced price controls on gasoline and other products.

These measures exacerbated economic hardships for the poor, and Venezuelans took to the streets to protest in deadly riots known as the Caracazo. Pérez survived two coup attempts in 1992 only to be impeached and forced out of office for embezzlement in 1993.

Popular anger against economic conditions and the dominant political class led voters to back more polarizing politicians. The first coup attempt against Pérez in 1992 was organized by Hugo Chávez, then a lieutenant-colonel, who famously exclaimed to the nation that he had failed “for now.”

He was right. Just six years later, in 1998, he ran for president and won an overwhelming victory.

Building support

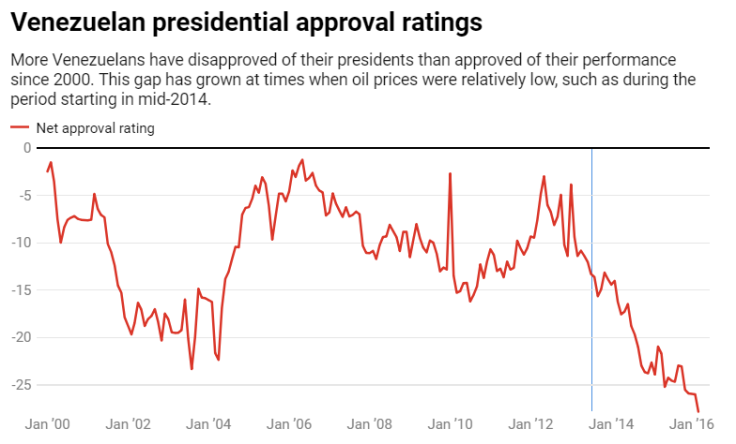

Luckily for Chávez, oil prices had started to rise again, eventually reaching record levels while he was in power. Aside from a brief downturn brought on by the Great Recession, those high oil prices raised enough revenue to help sustain his support.

He gained extra revenue by restructuring Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), the country’s state-owned oil and natural gas company that now faces U.S. sanctions, to increase his control and to direct a bigger percentage of its export earnings into government coffers.

With that money, he built popular support by paying for dozens of safety net programs, such as the “Barrio Adentro” health initiative for the poor and the “Misión Robinson” literacy program, starting massive infrastructure projects, and continuing to subsidize the world’s cheapest gasoline.

When Chávez appointed allies to prominent posts at PDVSA in 2002, dissident members of the military and radicalized leaders of the Venezuelan Federation of Chambers of Commerce staged a coup attempt that ultimately failed to oust him.

Meanwhile, the government invested too little in the oil industry and mismanaged it. At the same time, it did too little to prepare for the possibility of lower revenue from oil, to boost other exports or to stop depending on the United States as its biggest customer. Following a big decline, Venezuela remained America’s third-largest source of foreign oil as of October 2018.

Maduro’s staying power

Maduro arrived to power in 2013, after the 58-year-old Chávez died from cancer. By then, Venezuelan oil production had declined, and just one year later global oil prices began to collapse.

Maduro’s popularity collapsed too, although he did get re-elected in 2018 in a race without any independent international electoral observers that was marked by boycotts, accusations of repressing the opposition, and vote-rigging.

On top of his misfortune to be leading Venezuela during an oil price slump, Maduro has turned out to be even worse at managing the oil industry than Chávez. He installed military cronies as managers, led by Manuel Quevedo, a major general in Venezuela’s National Guard.

Since his rise, there have been more purges of PDVSA executives, and many reports that lower-level workers are staying home since they can no longer afford the commute on their wages. Adding even further to the commotion, corruption has run rampant.

The increased social and economic upheaval has even led many poor people to withdraw their allegiance to Maduro. Amid the turmoil, the U.S. and many other countries are recognizing opposition leader Juan Guaidó, as the nation’s legitimate president.

Whether or not Guaidó manages to dislodge Maduro’s grip on power, the country’s turbulent history suggests that long-term success will require much more than removing its current embattled leader. Any future leaders must also build the coalitions and institutions necessary to break the resource curse and thus empower Venezuela to finally draw social and economic stability from its oil wealth.

Scott Morgenstern is a professor of Political Science at University of Pittsburgh. John Polga–Hecimovich is an assistant professor of Political Science at the United States Naval Academy.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the article here.