Will Afghanistan Survive The Aftermath Of Its 2014 Presidential Elections? Will A Former Warlord Or Pro-Western Technocrat Replace Karzai?

The April 2014 Afghan presidential elections is one of the most important political tenure's Afghanistan will go through since the ousting of the Taliban 12 years ago. But many experts are skeptical that a country plagued by extensive political corruption, increased security challenges and a growing opium trade will prosper, especially in light of Afghanistan's past two flawed election processes.

The election means more for Afghanistan than selecting a new president. It means the country could have the first peaceful democratic transfer of power in its modern history, in the year when the U.S.-led international forces (ISAF) that have been in the country since 2001 will leave.

The current president, Hamid Karzai, was first appointed by a national assembly in 2001 as the interim leader and then went on to win two elections. Based on Afghanistan’s constitution, he is barred from running for a third term.

“This year’s presidential election can provide a critical opportunity for a renewal of legitimacy, a boost in confidence and a start to correcting the ineffective and corrupt governance that characterizes Afghanistan,” Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow with the Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence in the Foreign Policy program at Brookings, a non-partisan Washington think tank, said.

But Brown warned the election could trigger “extensive violence, a prolonged political crisis that paralyzes governance and the collapse of international support,” which could strengthen the Taliban.

In 2009 the U.N. fraud-monitoring panel nullified around a third of Karzai’s votes from the previous year’s election because of “clear convincing evidence of fraud.”

A subsequent runoff election was canceled as Karzai’s challenger, Abdullah Abdullah (a frontrunner in this year's election), withdrew his candidacy because he said it would result in widespread fraud, according to Brown.

The 2009 and 2010 elections left NATO with “little hope of ensuring even a procedural level of democracy in Afghanistan,” a report by Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government stated in December. “In addition to a fraudulent election process and a politically compromised electoral commission, election day security was lacking throughout the country, despite NATO ISAF efforts.”

Karzai’s presidency is also marred by several corruption scandals, one of which included his half-brother Ahmed Wali Karzai, suspected of trafficking large amounts of heroin through an intermediary, according to American officials. He denied the charges.

Back in April 2013, the New York Times revealed that tens of millions of dollars poured from the CIA to the office of Karzai. Not surprisingly it was alleged that his brother had been on the CIA’s payroll for years. He was assassinated in 2011 by a police commander believed to have been influenced by the Taliban.

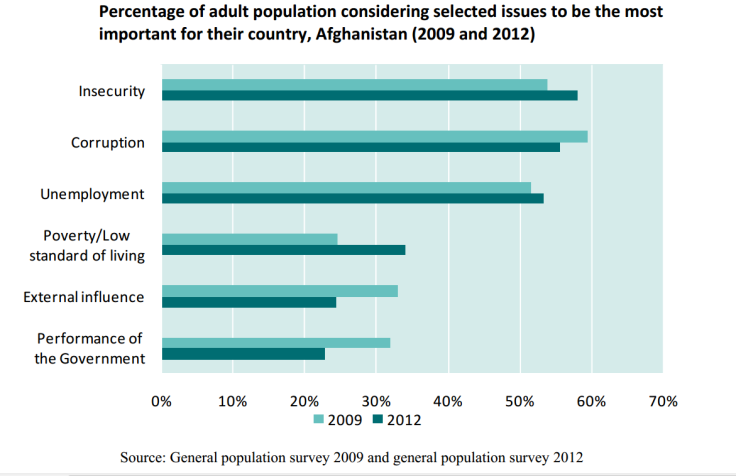

A 2012 study revealed that the Afghan population considered corruption, together with insecurity and unemployment, to be one of the major challenges facing the country, ahead of poverty or the performance of government.

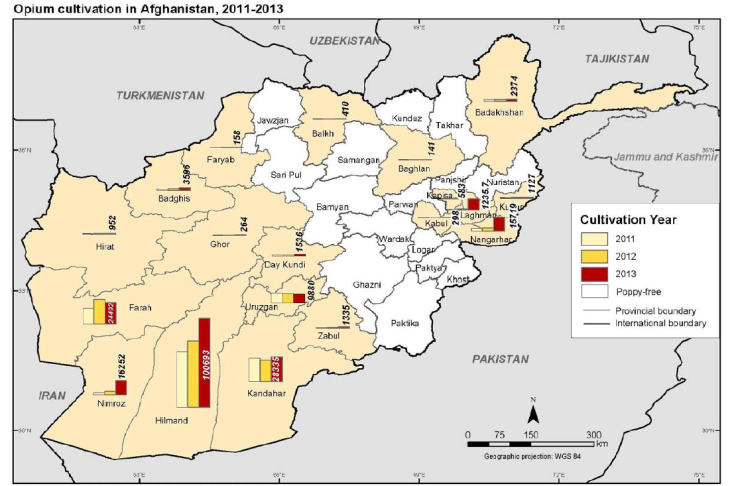

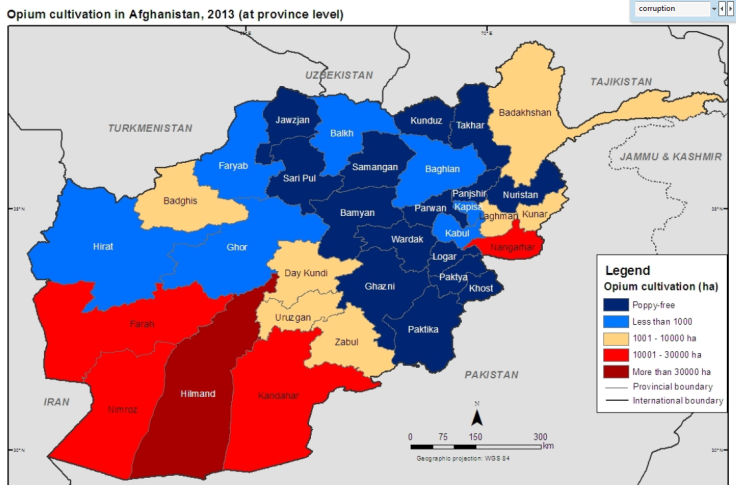

Another challenge Afghanistan faces after the withdrawal is the growing opium poppy trade, which reached a record high in 2013. According to the 2013 Afghanistan Opium Survey, cultivation amounted to some 209,000 hectares, surpassing the earlier record in 2007 of 193,000 hectares, and a 36 percent increase over 2012. It is considered the most important cash crop and provides for many households in rural areas. Today it represents around 4 percent of Afghanistan's gross domestic product (GDP), officially. But it also fuels conflict and undermines governance by providing income to insurgents.

In 2013, 89 percent of Afghanistan’s opium farming took place in regions that were classified as “high” or “extreme” security risks by the U.N.’s Department of Safety and Security. Most of these regions are inaccessible to the UN and to NGO’s.

One possible explanation as to why opium cultivation increased in 2013 may have been caused by “speculation due to the withdrawal of international troops and the forthcoming elections in 2013, which led farmers to try to hedge against the country’s uncertain political future,” a United Nations reported stated in November.

The election and transfer-of-power process are seen as indicators of Afghanistan’s future success after the U.S.-led ISAF coalition leaves this year.

But the withdrawal could leave a political, security and economic vacuum, making Afghanistan at risk of becoming a failed state. In fact its economy could fall by 10 percent after the pullout, according to the World Bank.

Afghanistan’s economy is largely dependent on international assistance as well as the presence of coalition forces in the country, which generates demand for goods and services.

In 2010 to 2011 the civilian and security-related assistance was the equivalent to 98 percent of Afghanistan’s GDP, and with the transition Afghanistan will have to rely more on domestic revenue generation to meet its budgetary needs.

But the international presence has drawbacks. too. “The obvious downside of such internationalization however is that it perpetuates a statehood depleted of internal sovereignty, which conflicts with official claims to increase local ownership, sustainability, and legitimacy in line with democratic ideology,” the Harvard report stated.

The question now is, who will lead Afghanistan into an uncertain future? This year’s elections will see 11 candidates, ranging from Western-educated technocrats to former warlords with bloody histories.

The frontrunners

Prof. Abdul Rab Rassoul Sayyaf

An ethnic Pashtun like most of the Taliban, Sayyaf is a religious conservative who at one point had links to Al-Qaeda and was a mentor of Khaled Sheikh Mohamed, the mastermind of 9/11, according to Felbab-Brown. He was born in 1944 in Kabul province, and is one of the most controversial candidates among the warlords running in the election. But over the years Sayyaf has changed his views and has been a strong Taliban critic. In fact the Taliban have designated him "the manifestation of Satan," as reported by The Economist. He is also one of the Taliban’s most high-value targets.

Dr. Abdullah Abdullah

From 1992 to 1996, Abdullah served as a spokesperson for Afghanistan's Defense Ministry and subsequently as Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was in charge of foreign affairs for the government-in-exile of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, led by President Burhanuddin Rabbani from 1999 until the collapse of the Taliban regime. In 2009 he finished second behind Karzai, in an election that was marred by fraud and corruption. Ethnically, an important factor in a nation where ethnicity can largely determine destiny, he is Tajik and Pashtun.

Abdul Qayyum Karzai

Abdul Karzai, a businessman and former member of Afghanistan’s parliament, is the older brother of Hamid, the current president and head of the Karzai clan, who are Pashtuns. While Hamid has not yet endorsed his brother, or any other candidate, Abdul has the name recognition that could give him a slight advantage in the race, but if he wants to be a truly serious contender he would have to leverage his brother’s political weight. While he may be viewed more favorably by the U.S. than Hamid, he is still considered part of Afghanistan's corruption system.

Dr. Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai

Ahmadzai, born to an influential Afghan Pashtun family in 1949, was the finance minister during the transitional administration after the Taliban regime fell. A technocrat, Ahmadzai partnered up with his former archenemy, General Abdul Rashid Dostum, a powerful Northern warlord who was a key U.S. ally against the Taliban. Ahmadzai ran in the 2009 elections but won only 3 percent of the vote. The partnership would give Ahmadzai the political support needed in order to become a viable candidate, if he can get the votes of ethnic Uzbeks from North Afghanistan who support Dostum.

Zalmai Rassoul

The French-educated doctor is a part of Karzai’s inner-circle. Rassoul, a Pashtun, was Karzai's national security advisor for eight years, and in 2010 became Foreign Minister. In early October he resigned from his position in order to run in the presidential race. In a Wall Street Journal interview in November, Rassoul explained why he decided to run: “This is not a normal election. This is the first time in our history that an elected president will replace another elected president. So if that happens -- hopefully -- the democratic process will really start to take root in Afghan society."

Abdul Rahim Wardak

Another former mujahedeen commander, who fought the Soviets in the 1980s, Wardak attended the U.S. Army’s staff college at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He was also Afghanistan’s defense minister. Wardak called for the signing of a security pact with the U.S. as soon as possible, something that Hamid Karzai has threatened to postpone if the U.S. does not meet his demands.

“It is a requirement for the future survival of this country. And it is a requirement that the international community continues its support for Afghanistan," Wardak, a Pashtun, told Wall Street Journal. "Without it, I think this country will go back to square one …The threat is such that no country in the world can defend it alone -- regardless of how big a country is or how strong a country is."

Candidates Who Most Likely Don’t Stand a Chance

Gul Agha Shirzai

Also a Pashtun, Shirzai (on the left in the picture, with President Karzai) was a former mujahedeen commander and governor of Kandahar province, prior to the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in 1996. After the U.S. invasion in 2001, Shirzai returned to his governorship again and then in 2006 became the governor of Nangarhar province. U.S. officials say that he used his position for his own personal gain by collecting unauthorized taxes on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

Hidayat Amin Arsala

Born in 1941 to an influential Pashtun family in Kabul, Arsala became the first Afghan to join the World Bank, in 1969 until the late 1980s. In 1987 he joined the mujahedeen in fighting against the Soviets and later served as finance minister in the interim government from 1989 to 1992. He also served as Karzai’s senior advisor.

Qutbuddin Hilal

Hilal, an engineer and a Pashtun, might be the most controversial candidate as he is a member of Hezb-Islami, an Afghan militant group which carried out a suicide attack in Kabul in February, killing two contractors for the coalition forces and wounding several Afghan civilians. If elected, Hilal would seek to change Afghan’s constitution as he sees certain articles pertaining to human rights and women’s rights as a conflicting with adherence to Islam, Hilal told tolonews.com.

Sardar Mohammad Nader Naeem

Born in 1965 in Kabul, th Pashtun Naeem is the grandson of Sadar Dawood Khan, a former president of Afghanistan. In 2012 he launched a new political comapign known as the Woles Ghag, the Voice of the Nation. In a recent interview Naeem addressed Afghanistan’s struggle with corruption, saying that corruption needed to first be fought by upper echelons of leadership."We can't eliminate corruption in general, water should be clean from the source," Naeem, told tolonews.com. "Honest and patriotic individuals should be placed in higher offices.”

Mohammad Daud Sultanzoyi

A former TV talk show host, and a Pashtun, Sultanzoyi is now a leading analyst on internal and foreign affairs of Afghanistan. He was elected a member of parliament in 2005, but lost his seat in 2010. He was also the chair of the Afghan Parliament’s Economic Committee.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.