Will Hedge Fund Millionaires Flee South If They Face Higher Taxes? Wall Street Fights Move To Close Loophole

During his presidential campaign, Donald Trump pledged to eliminate tax provisions that allow Wall Street money managers to pay a lower tax rate on their compensation than most middle-class people pay on their income. Financial executives taking advantage of the tax maneuver “are getting away with murder,” he said. Yet since taking office — and subsequently populating his administration with finance industry moguls — Trump has gone silent on the issue.

That does not mean the fight over the carried interest tax loophole is dormant: On the contrary, in states near the New York City epicenter of the hedge fund and private equity industries, lawmakers are pursuing a coordinated strategy to close the loophole and recoup billions for their state’s operating budgets.

In the last few months, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island have all introduced bills that would add a new tax on investment manager profits. Lawmakers have also introduced similar legislation in Illinois, a state with a nearly $10 billion budget shortfall. Though polls show that closing the loophole is popular, the state initiatives face a powerful opposition: Records reviewed by International Business Times show that the financial industry — which has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on state politics — has in many cases lobbied on the measures. In three of the states, the current governors came into public office from the financial industry that benefits from the loophole.

As it stands now, when hedge fund and private equity executives generate investment gains for their clients, they typically keep a slice of those gains — known as carried interest — as compensation for their financial management services. But rather than classify that compensation as income, many of the executives classify the money as their own capital gains, thereby allowing them to pay the lower capital gains tax rate. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the loophole permitting this maneuver will cost federal taxpayers $20 billion in lost revenues over the next decade.

The loophole also results in lost state tax revenue, and so the new state bills propose to implement a 20 percent investment income tax. That would mean that between the federal capital gains tax (20 percent) and the new state taxes, the profits that hedge fund and private equity managers make would be taxed at the current federal tax rate for the highest earners — about 40 percent. (The federal income tax rate for the $ 37,651 to $91,150 bracket is currently 25 percent.)

Some, including Hillary Clinton, have argued the president could unilaterally order the Treasury to change the way it taxes carried interest. But with Trump silent on the issue, and with bills to close the loophole stalled in Congress, state lawmakers have taken action.

“There have been off and on efforts at the federal level to close the loophole for many years,” Michael Kink, executive director of the Strong Economy for All Coalition and a member of The Hedge Clippers, an anti-hedge fund advocacy group, told IBT. Kink said he has been working for the last year and half with progressive groups and labor unions, including the American Federation of Teachers, to create legislation to address the loophole at the state level.

“As much as politicians would scream and yell about it, Wall Street would be able to buy influence to stop anything from happening,” Kink said. “It became clear these guys really had Washington on lock.”

The states have formed what Kink calls “a compact”: an effort to make sure none of the states loses private equity and hedge funds, or their wealthy managers, to other states in the region. All the bills contain language that makes enactment contingent upon other states in the compact passing similar bills. Trying to capture billions of dollars in hedge fund profits in the region, the states are betting that Wall Street types won’t pick up and move out of New York City’s orbit.

“Some of the wealthiest Americans are getting a lower tax rate than firefighters, teachers, police, you name it,” said Democratic assemblyman Troy Singleton of New Jersey, who introduced a bill to close the carried interest loophole last June. “Hopefully, we can get this addressed on the federal level, and if not, hopefully our states can pave the way.”

Some fellow Democrats in the region would rather see the loophole issue addressed in Washington, D.C., and not in state houses.

“It’s not a discussion that’s in the best interest of Connecticut to lead,” Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy said in January about a Democratic bill in Connecticut to raise an estimated $520 million in revenue by closing the tax loophole. “Because we have employers who have large numbers of employees in our state and I just don’t think that’s an area that we should stake out.”

“A Disincentive To Invest”

There are currently 9,388 hedge funds and 4,281 private equity funds in the U.S., according to Preqin, an alternative investment research group. Roughly 45 percent of those hedge funds and 30 percent of those private equity firms are in New York state. Together, the states in the compact are home to nearly 60 percent of U.S. private equity funds and two-thirds of all U.S. hedge funds, as well as more than half of the $3.22 trillion that U.S. hedge funds manage, and more than 30 percent of the $2.49 trillion controlled by private equity, according to Preqin.

It is unclear how much in additional tax revenue the bills would generate for the states, and estimates vary widely. A 2016 Congressional Budget Office analysis said closing the loophole at the federal level could produce an additional $19.9 billion in tax revenue between 2017 and 2026. But tax expert and University of San Diego law professor Vic Fleischer, who started the debate over carried interest in a 2006 academic paper before he began advising the Senate Finance Committee last year, has estimated closing the carried interest loophole would generate $180 billion over the next decade. Proponents of the New York bill say it could generate an additional $3.7 billion per year for their state, and estimates across the border have put the figure for Connecticut at more than $500 million annually.

The investment industry argues those numbers overestimate the revenue that could be created by closing the loophole, which some say doesn’t even fully apply to hedge funds, since the long-term capital gains rate applies only to profits on assets held for over a year. Anything held for a shorter time is taxed as income, and hedge funds hold many of their assets for less than a year while pursuing a variety of strategies, both long and short-term, to generate profits.

Private equity funds, however, typically hold assets — usually businesses — for years at a time while they improve operations, which sometimes means building a company, and other times means shedding workforces, before selling them at a profit, often by using leveraged buyouts. Managers do often invest some of their own money, but usually this is a very small percentage of the overall investment.

But managers have to make a profit to get the big payout. Private equity managers, like hedge fund managers, typically get 20 percent of profits, which is taxed as capital gains (they also usually earn a 2 percent management fee, which is taxed as income).

Closing the carried interest loophole “would not provide the economic windfall that’s being proposed in the legislation,” said James Maloney, vice president of public affairs for the American Investment Council, an investment industry advocacy organization. He argued the tax could cause investment to slow, which would shrink the tax base.

“I think you have to factor in that you are introducing a disincentive to invest and a disincentive for entrepreneurial risk taking, which has long been the model for success for the private investment industry,” Maloney said.

But supporters of closing the loophole don’t buy the argument that investment managers will somehow stop working because they are taxed at higher rates.

“These guys make a lot of money and they get paid very handsomely,” said Gregg Polsky, a tax law professor at the University of Georgia. “It’s hard for me to believe simply by raising their tax rates to the same rates that everyone else pays is going to cause them to pack up and take their ball and go home.”

Millionaire Migration

While the coalition of lawmakers introducing interlocked legislation admit their coordination is designed to prevent money managers from evading taxes by moving to another state in the New York region, they are willing to bet that financial executives will not move fully out of the sphere of America’s largest city. But that’s what billionaire hedge fund manager David Tepper did in late 2015, moving from New Jersey to Florida, which doesn’t have a state income tax. By moving, Tepper saved himself — and cost New Jersey — hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue.

The move validated recent efforts by Florida, and especially Miami, to attract hedge funds and private equity. Florida is now home to more hedge funds (309) than New Jersey (305), according to Preqin.

“It’s a strong environment in south Florida, and Miami, as far as hedge fund activity,” said Steven Klein, a partner at Florida accounting firm Gerston Preston. “It’s not huge, but we are seeing an absolute increase in that activity. I believe a lot of it is driven by what's going on in trying to close these loopholes.”

Klein said that although wealthy money managers usually have ties to New York because of their Ivy League educations and the city’s position as a major financial center, modern communications and the conveniences of extraordinary wealth make their jobs less dependent on physical location.

“They have a computer, they have private planes, they can be wherever they want in two hours,” Klein said.

However, research has shown that the wealthy are not necessarily likely to move when their taxes go up. A study by a pair of researchers from Stanford and Princeton examined whether or not New Jersey’s 2004 “millionaire tax” on residents making over $500,000 a year caused high-earners to flee the state. They found that those affected by the increase weren’t more likely to leave the state than those who made between $200,000 and $500,000 per year. The same researchers also examined tax increases on the rich in California, and found similar results.

“The highest-income Californians were less likely to leave the state after the millionaire tax was passed,” wrote researchers Charles Varner and Cristobal Young.

But even the possibility of states becoming tax havens is why proponents of the current bills would prefer to have the loophole closed at the federal level.

Efforts to do that in recent years have come up short. Calls for closing the loophole began after the Democrats took control of Congress in 2007, and private equity firms lobbied heavily against those efforts. For example, Mitt Romney’s Bain Capital private equity firm spent $1.5 million on lobbying in 2007 and 2008. Bills were introduced in 2010 and 2012 that included language that would have closed the loophole. President Barack Obama’s proposed 2015 budget closed the loophole to help pay for an expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit. In 2015, Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wisc., and Rep. Sander Levin, D-Mich., introduced legislation that focused solely on closing the loophole. But these efforts met with resistance that has been fueled in part by industry cash.

Private equity and investment firms contributed $16.5 million to politicians in the 2014-2016 election cycle. Hedge funds chipped in another $8 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. And one of the biggest beneficiaries of the financial industry is New York Sen. Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader.

The industry’s influence in Washington is why the states should act first, activists say.

“We’ve focused on the state efforts because we’ve raised it on the federal level,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, which has fought for the state bills.

“We care about fair taxation. We care about income inequality. And we care when people say there is not money in state and federal budgets and then we see that there is a huge corporate loophole, particularly for hedge fund guys,” Weingarten said.

$123 Million For State Lawmakers

States are hardly immune to influence from Wall Street. In the last decade, the securities and investment industry has poured more than $400 million worth of campaign cash into state politics — and $123 million of that has flowed into the six states now considering the carried interest tax bills, according to data compiled by the National Institute on Money In State Politics.

In Connecticut where Malloy is opposing the carried interest bill, donors from the securities industry have delivered more than $3.5 million of campaign donations since 2007. That included $115,000 to Malloy’s state Democratic Party during his two successful runs for governor. Malloy's administration has given Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, $22 million in grants and loans at a time when Malloy has pushed for big cuts to state services and is threatening mass layoffs of state employees.

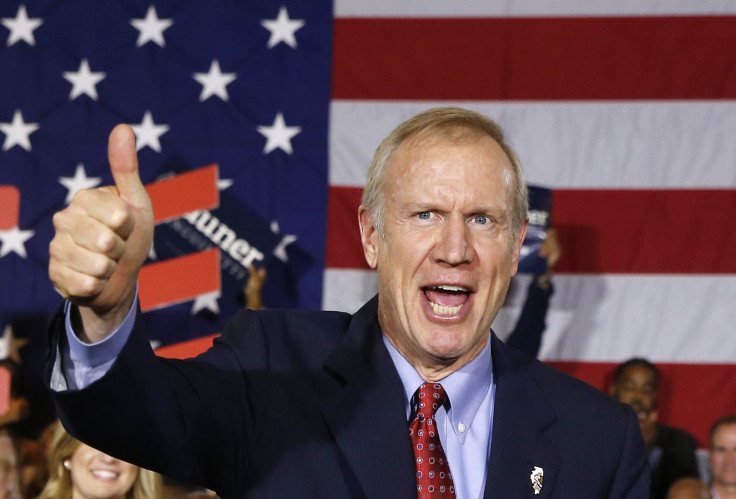

In Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Illinois, Democratic Gov. Gina Raimondo, Republican Gov. Charlie Baker and Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner, respectively, have not taken a public position on their state’s carried interest bill — but both have ties to the investment industry that benefits from the loophole.

Raimondo was an executive at the venture capital firm Point Judith. SEC documents filed in March show Raimondo retains an ownership stake in Point Judith, which manages Rhode Island state pension money. During her runs for state office, Raimondo has raised more than $360,000 from the securities industry.

Baker was an executive-in-residence at the venture capital firm General Catalyst before being elected governor. Baker credited the Republican Governors Association for making a "huge difference" in his 2014 gubernatorial bid. That year, the RGA's top contributors included firms from the investment industries that benefit from the carried interest loophole, including Elliott Management, KSL Capital, Citadel and Caxton Alternative Management.

Rauner was elected governor in 2014 with the help of hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin, who donated more than $13 million to the Republican’s campaign. Rauner himself has raked in millions from the loophole as one of the principals of the private equity firm GTCR. According to a Chicago Tribune review of his tax records, Rauner made $188 million in taxable income in 2015, and paid $50 million in taxes for a total tax rate of 26 percent.

Rauner still owns a stake in GTCR, according to SEC records. GTCR documents reviewed by IBT show that the firm says enacting legislation to close the carried interest tax loophole “could adversely affect the ability” of firm executives “to benefit from carried interest taxed at lower rates” and could make it harder for GTCR “to incentivize, attract and retain individuals to perform services.”

In New Jersey and New York, carried interest legislation was first proposed in 2016, and corporate lobbyists quickly swung into action. In New Jersey, state records show both AT&T and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, an industry trade group, lobbied on the bill. Similarly in New York, state records show Fortress Investment Group and Stephen Schwarzman’s Blackstone Group lobbied on the legislation.

Blackstone has said in its SEC filings that closing the carried interest loophole would “materially increase the amount of taxes that we and possibly our unitholders would be required to pay, thereby adversely affecting our ability to recruit, retain and motivate our current and future professionals.”

Also lobbying on the New York bill was the New York State Business Council, which includes Wall Street giants J.P. Morgan and Morgan Stanley among its members.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has not taken a public position on the bill, but Bill Mulrow, who served as the governor’s chief of staff for more than two years before resigning earlier this month, recently returned to his position at The Blackstone Group. Mulrow, who was a registered lobbyist for Blackstone before working for Cuomo, is set to serve as the chair of Cuomo’s 2018 reelection campaign while working at the private equity firm.

That kind of cross-pollination between the hedge fund industry and New York politics isn’t uncommon, the Hedge Clippers say. According to the group, hedge fund managers gave $39.6 million in political contributions to New York state politicians between 2000 and 2014, with $4.8 million of that cash going directly to Cuomo's campaigns for attorney general and governor.

While the push to change state tax laws governing the finance industry is new, the debate over carried interest is part of a much older debate about capital gains and income. Since Congress established a separate capital gains tax rate in 1922, there have been efforts to make income look like capital gains, and arguments over whether specific sources of profit should be considered capital gains or income, said Adam Rosenzweig, a professor at the University of Washington School of Law in St. Louis.

“Nothing in this debate is new,” Rosenzweig told IBT, explaining that in decades past, these arguments have touched on everything from film credits to cattle futures. “This is a new application for an old tension in the law. And that tension is treating income and capital gains differently.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.