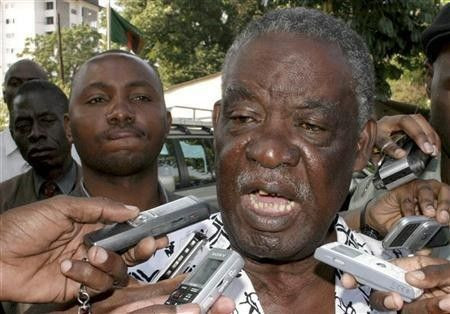

Will Zambia Husk Its Corn Meal Subsidies? President Michael Sata Eyes Cuts In Government Subsidies

President Michael Sata is hellbent on reigning in government expenses, and with fuel subsidies cut, are corn millers next?

Zambia’s President Michael Sata is eyeing state subsidies and sharpening his scythe.

Last week, Africa’s biggest copper producer removed a subsidy on fuel prices that Sata, who rode into office promising a wave of anti-corruption reforms, said benefited only wealthy car owners. He estimated that maintaining the incentive would have cost 1.1 billion kwacha, or about $207 million, Bloomberg reported, and he needs that money to improve the country's lethally poor roads.

As the president -- nicknamed “King Cobra” for his sharp-tongued critiques of his rivals and, in one instance, George W. Bush – continues his stated mission to “lower costs in the economy,” what will be next?

One option: Corn meal subsidies.

In January, Sata called on millers to make the coarse corn flour locally known as “mielie meal” affordable for the population. Sata wields the power of a price control over the national staple.

At the start of Sata's rule in 2011, the country enjoyed bumper harvests, according to the United Nations’ Food & Agriculture Organization. In recent months Zambia has increased its exports of corn to its neighbors in southern Africa, particularly to Zimbabwe. And in September, the branch of USAID that monitors early warnings of famine ranked the country’s food insecurity levels at minimal.

But armyworm infestations and particularly wet seasons have cut yields, driving up the cost of food, James Kimer, the editor of ZambiaReports.com, told International Business Times.

The price of milled corn nearly doubled in the latter half of last year to $15 per 25-kilogram bag, according to the Wall Street Journal.

"We would see a massive rise in smuggling and worsening of shortages of mielie meal in crucial areas, such as the Copper Belt and some others," he said over a Skype call. "We’ve seen this before in the past – the possibility of unexpected public protests and riots cannot be discounted."

Compounding that are fears that the now-defunct 15 percent fuel subsidy, which Kimer said Sata slashed without notice, will drive the price up further as the cost of transportation rises with petroleum.

So, why cut the millers subsidies?

A September study by the Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute, a think tank based in the capital Lusaka, found that subsidies to millers and retailers were rarely passed on to urban consumers, who are now paying the highest rates since Sata took office two years ago. The study also said that the subsidies go to select millers and therefore stifle competition.

To boot, the subsidy program did not appear in the administration’s original budget, according to the institute, “[crowding] out public investments with proven impacts on agricultural growth.”

If cutting the subsidies did drive up the price of corn meal, the results could be disastrous.

In the 1980s, high costs and short supply of food caused riots in the region.

Under former President Rupiah Banda, who is now facing a corruption trial, Kimer said the the same bag of mielie meal that costs about $20 now was worth $5.

The cost of not putting food on the table may be too high a political price for Sata.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.