Winter Cold Snap In US Intensifies, Lake-Effect Snows Pummel Northeast And Midwest

After a few months of a relatively mild winter, North America got a rude awakening this January.

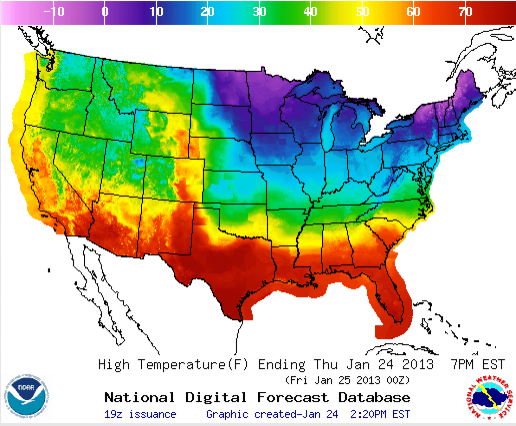

Early on Thursday, 12 states east of the Rocky Mountains saw temperatures fall below zero. The township of Embarrass, Minn., nicknamed the Cold Spot, lived up to its moniker, recording the lowest temperature in the U.S. Thursday morning, hitting -42 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Weather Underground meteorologist Jeff Masters.

That's pretty chilly, but not low enough to be the all-time record of -57 degrees Fahrenheit set in 1996, according to the township's website.

Freezing air moving south from the Arctic has stirred up what are known as lake-effect snows across the Midwest and Northeastern U.S. Some areas in upstate New York have seen snow piling up more than three feet.

The recipe for lake-effect snow is roughly this: A mass of cold air moves over the warmer waters of a lake. The warmth of the lake water heats up the bottom of the cold air mass, and some of the lake evaporates up into the cold air. After it rises for a little while, the warm air cools, and the moistrue from the lake condenses into clouds and gives rise to snow.

These recent lake-effect snows are thought to be especially bigger thanks to the mild winter months beforehand, which have warmed the Great Lakes to an unprecedented degree. The Great Lakes have also seen lower than average ice coverage this season, which helps pump up the snow.

“If the lakes are frozen, they generate very little in the way of lake effect snow, since little moisture can escape upwards from the ice,” Masters wrote on Wednesday.

The warming of the Great Lakes plays into a cycle similar to one currently seen in the dwindling ice coverage in the Arctic.

“The amount of warming of the waters in Lakes Superior, Huron and Michigan is higher than one might expect, because of a process called the ice-albedo feedback: When ice melts, it exposes darker water, which absorbs more sunlight, warming the water, forcing even more ice to melt,” Masters wrote.

The cold snap is supposed to lighten up a little bit next week. For most of us, our only recourse is to bundle up, but some other creatures have more unusual strategies to beat the cold. The wood frog, for example, hibernates but doesn't seek out a cave; it simply stays put and freezes in the cold. It doesn't die, though, thanks to a unique survival technique.

Before the coldest part of winter hits, a wood frog's blood glucose levels increase over eight hours until they hit levels as much as 200 times greater than normal.

“This 'antifreeze' effect preserves tissues and organs through the long winter,” Audubon Guide writer Kent McFarland explained in 2010.

It doesn't stop there. The wood frog's body really, literally freezes, with ice crystals running between skin and muscle and encasing internal organs. The frog's eyes also turn white with frost. And when spring comes, the wood frog, like the forest around it, thaws and begins anew.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.