Young Voters Don’t Like Hillary Clinton Or Donald Trump: What That Means For November

There’s “no friggin’ way” Neil Spencer would vote for a Republican for president, but he’s not ready for Hillary, either. Spencer, a 20-year-old senior at Florida State University in Tallahassee, said he believes nearly all politicians are corrupt, a stance he started forming in high school after taking an Advanced Placement American history course.

Now a senior majoring in political science and international affairs in a swing state that often decides national elections, Spencer said he probably won’t vote this November if his choices are Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. He’s scrutinizing issues like healthcare, trying to figure out why people like his grandparents have to slave away to afford their insurance deductibles while countries like France provide coverage for free. He’s keeping an eye on the economy, because he grew up during the Great Recession. He’ll also be watching presumptive nominees Trump and Clinton over the next few months: whether they adjust their platforms, whether they resort to attack ads and whether they consider millennials a true constituency.

“I don’t want to reward my vote, which is mine and mine alone, to somebody who’s either a bully or feels entitled,” Spencer said. “Whipping and [doing the] Nae Nae on 'Ellen' just comes off as really 'ugh' to a lot of us. We look at that and we're like, 'Could you not? Could you just treat us as if we're real human beings?'"

With Clinton and Trump, two politicians about as widely disliked as they are liked, racking up delegates in the primaries, the United States presidential race is about to get even nastier. While attacking each other may score the former secretary of state and billionaire the votes of baby boomers and Gen Xers, campaign veterans say the technique might not motivate younger people to cast ballots in their favor. In fact, negative ads and candidate pandering could prompt many millennials to skip the polls entirely, depressing turnout among a crucial demographic that has increasingly determined who wins the White House.

“Why does a young person want to vote? They want to vote because they want to make a difference. They want to do what is in their best interest,” said Eric Zoberman, the national youth vote deputy director for President Barack Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign. “When you make that a negative experience, when you paint a picture that a young person has to choose the lesser of two evils, it takes that enthusiasm out of the process.”

What young voters think about politics matters, if only because their age group is so large. In 2008, about 51 percent of people between 18 and 29 voted in the presidential election, totaling about 22 million and backing Obama over Republican nominee John McCain by a two-to-one margin. In 2012, Obama again nabbed the youth vote, with about 45 percent of young voters heading to the polls.

Their influence last cycle was enormous. Obama's support from voters over 30 waned when he faced challenger Mitt Romney, but he won in part because he still had an advantage among young people.

Obama ended up with 332 of the nation's 538 electoral votes to Romney’s 206. Youth were the deciding factor for 80 of them, according to data from the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. Had half of 18- to 29-year-olds in Ohio, Florida, Virginia and Pennsylvania voted for Romney or abstained, those states would have gone red.

Take Ohio, for example, where CNN showed total voter turnout was just over 5,489,000, about 17 percent of which were people under 30. Obama took home about 2.8 million votes and Romney had 2.7 million. But without youth support, the balance flips. When young voters are subtracted, Obama had 2.2 million votes to Romney’s 2.3 million. That means Romney could have won the popular vote — and Ohio’s 18 electoral votes. Repeat that scenario in a few other swing states, and he could have won the presidency.

This November, Ohio is just one of 10 states where the youth vote could be especially influential. According to CIRCLE’s Youth Electoral Significance Index, which looked at factors like how close the race will be and how many youth are enrolled in college, millennials could heavily influence the outcomes in New Hampshire, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Colorado, Wisconsin, Virginia, Florida, North Carolina and Nevada.

The definitions of the "youth vote" and "millennial generation" vary depending on who you're talking to. The youth electorate usually includes voters under the age of 30, while millennials can be as old as 34. The overlap means the terms are often used interchangeably.

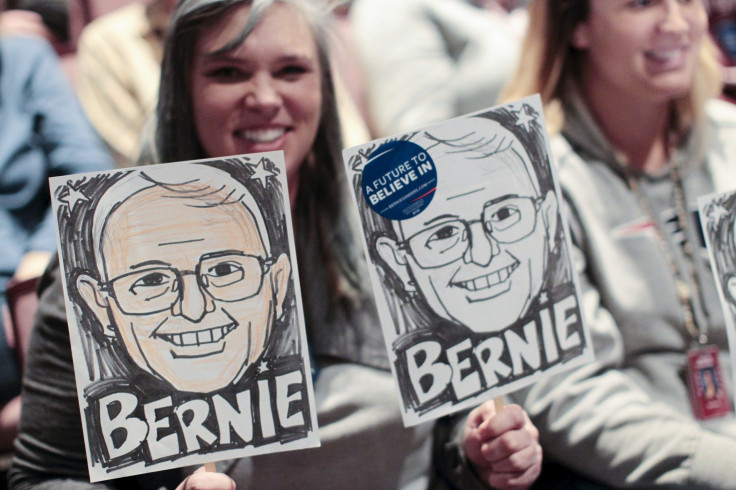

But no matter the parameters, campaigns seem to know how important the demographic is. Over the past few months, candidates in both parties have scrambled to endear themselves to Generation Y. Recent dropout Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., repeatedly said he listens to the Wu Tang Clan. Trump challenger Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Ky., created a Snapchat filter for a GOP debate. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., hosted a Vampire Weekend concert before the Iowa caucuses, and Clinton danced to the popular hip hop song "Watch Me (Whip/Nae Nae)" on "Ellen" before taking a selfie with Kim Kardashian and Kanye West, also known as "Kimye."

Tori Hall, a political science and Spanish third-year student at Ohio State University in Columbus, said her peers are constantly discussing the election, even though it's only March. She compared the atmosphere to football season when everyone's always talking about the Buckeyes. Now, the presidential race is the hot topic.

One of Hall's personal political interests is income inequality, because "something's obviously wrong and needs to be fixed," she said. She finds evidence for that in her own upbringing: Hall is paying for college herself. Her parents live paycheck to paycheck despite both having masters' degrees.

"We went a winter without heat because we couldn't afford the gas bill," she said. "In the U.S., one of the wealthiest countries in the world, there shouldn't be anybody going through that."

Hall suggested she and other millennials have soured on traditional politics because they've inherited problems from previous generations. For example, nearly 70 percent of seniors graduating from college in 2014 reported having student loan debt — an average of nearly $29,000 per person, according to the Institute for College Access and Success, an independent nonprofit based in Oakland, California. The number of young women living with their parents — about 36 percent — hasn’t been so high since 1940, according to the Pew Research Center.

"I'm 20. When I was 6, that's when 9/11 occurred. Then we entered two wars before I was even 8 years old. By 2008, we were in a financial crisis," said Hall, a board member for her school's Students for Bernie club. "We're coming to terms with that and [looking for] the best candidate we can find who's not part of the establishment."

Hall said the candidates ramped up their outreach efforts right before the state's March 15 primary, and she even got to attend CNN's Democratic town hall on campus at the Mershon Auditorium. Halfway through, the producers needed students to fill front-row seats, so they moved her up.

If social media is any indication, Hall’s not the only college student paying attention to the campaigns. In the four months before the 2014 midterm elections, 43 million Facebook users in the U.S. generated 272 million politics-related interactions, which included likes, posts, comments and shares. Last year as a whole saw 76 million people on Facebook generate 1.7 billion interactions about the elections.

But just because people are talking about the candidates doesn't mean they like them. Clinton, who as of Monday had won 1,712 of the 2,383 delegates needed to cinch the Democratic nomination, is unpopular with many Americans. About 52 percent of respondents to an ABC News poll earlier this month said they saw her unfavorably. Trump, who had 739 of the 1,237 delegates necessary for the Republican gig, was doing even worse than the former first lady. More than two-thirds of respondents told ABC News they saw him unfavorably.

“No one who’s likely to be nominated has a net positive rating, which is almost unprecedented in American modern history,” said Bob Shrum, a Democratic political consultant who worked on John Kerry and Al Gore's campaigns for the presidency. “It’s not as if their positive messages at this point are compelling… you can depend on a lot of negative advertising.”

In a scenario where the nominees are unable to convince undecided voters they’re the best choice, they’re left convincing voters their opponent is the worst choice. Shrum noted this isn’t a new phenomenon. “That’s been going on since [Thomas] Jefferson and [John] Adams ran against each other” in 1796, he said.

Both 2016 front-runners have considerable resources. Clinton and organizations supporting her had spent $14.6 million on ads as of January, and Trump and his backers had bankrolled $2.2 million’s worth, according to NBC News.

What form the mudslinging will take — and how it will play with young voters — is still unclear. Research on whether millennials respond to negative ads is surprisingly scarce. A 2012 study from Arizona State University found that more than 80 percent of people polled said they either somewhat or strongly agreed that some negative ads are “so nasty that I stop paying attention." The survey’s findings were not broken down by age.

But there’s a reason campaigns use negative ads: They work. Shrum pointed to a series of 2012 TV commercials that taught viewers about Romney’s ties to Bain Capital, a private investment firm accused of outsourcing jobs.

Strategists in 2016 certainly have plenty of fodder for their attack ads. On the Republican side, there’s Trump, who’s quickly gained a reputation for making controversial comments on issues like gun control and the Syrian refugee crisis – both of which millennials have named as policy priorities for the next president. Clinton will likely be hit with character ads about her trustworthiness, given that she served in the Obama administration during the 2011 Benghazi attack and was later discovered to have used a private email server.

“I doubt you’ll see great deal of ads targeted at millennials about how Hillary Clinton is wonderful,” said Kristen Soltis Anderson, a pollster who wrote the book “The Selfie Vote: Where Millennials Are Leading America (And How Republicans Can Keep Up).” “Instead, you’ll see, ‘You have to go vote for Hillary Clinton even if you don’t like her that much because these Republicans want to turn us back to the time of the dinosaurs.’”

The dirty politics have already begun. On March 16, Trump released an online ad that flashed clips of Russian President Vladimir Putin and an Islamic State group fighter before telling viewers that the Democrats had “the perfect answer” to U.S. opponents. The video then flipped to a recording of Clinton barking like a dog at a campaign rally.

A pro-Clinton super PAC immediately fired back with an ad labeling Trump a punch line. It played a recording of Trump’s response to a reporter asking who he’s been consulting on politics — “I’m speaking with myself, number one, because I have a very good brain and I’ve said a lot of things” — and showed a clip of Clinton laughing.

The group of voters put most at risk from these kinds of negative ads could be young millennials, or those between ages 18 and 21. People who have voted before tend to stay politically engaged and vote again, but if they’re new to the process they might skip it entirely, Anderson said.

“There’s a chance you could just see them deciding, ‘This seems horrible and I’m just going to stay home,’” she added.

History indicates that whether young people vote in large numbers depends partially on whether they're excited. After 1972, which was the first general election after the voting age was lowered to 18, turnout among 18- to 29-year-olds didn't exceed 50 percent until 1992, when Bill Clinton ran for president. Turnout then slipped back under the halfway mark until 2008.

Former Obama staffer Zoberman credited Obama’s early momentum in that election to his optimistic persona as “a pie-in-the-sky candidate.” He said that for young people, Obama’s attitude was just as important as his platform. That’s why, in Zoberman’s view, doomsday-type advertising could be particularly ineffective among youth this year: They’re hopeful about not only their own futures but the future of the country.

Young people have ranked integrity, level-headedness and authenticity as the top attributes they want in a president, and the rise of Clinton rival Sanders could be proof they mean it. The Democratic candidate has become particularly popular on college campuses for encouraging a political revolution, vowing to bust open corruption on Wall Street and refusing to run a negative campaign. According to exit polls, Sanders got 83 percent of young peoples' votes in the first-in-the-nation New Hampshire primary. He later won the youth vote in eight states on Super Tuesday.

Zoberman, also a former national field director for the nonprofit youth voting organization Rock the Vote, recommended the candidates capitalize on millennials’ good feelings about democracy by demonstrating they relate to and understand young people’s concerns. He said that, going forward, they should subtly point out differences in policy in a respectful way.

“We are more attracted to like-minded, generally good, inclusive, nice people,” Zoberman said. “When it becomes bitter, when those differences are pointed out through biting, one-line attacks and condescending tweets — that doesn’t [work].”

Lawmakers trading insults on social media couldn’t be farther from the reason Frank Pray, chairman of the College Republicans at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, initially became involved in politics.

Pray, now 21, said he followed his conservative parents’ leads until he started attending his Catholic middle school. That’s when he had a teacher whose son was serving in the Marine Corps in Afghanistan. Pray said he realized that if people were willing to die for the country, the least he could do was pay attention to who was running it. He learned about 1964 Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater and started checking what candidates’ stances on issues like gun control were.

Pray said he intends to vote for whoever the Republican presidential nominee is. But as the campaigns progress, he said he’d rather encounter substantive negative ads than petty ones.

“I like to see people saying why somebody’s not good at what they did rather than, ‘They’re a terrible person; we should tar and feather them,’” he added.

However, ads can only do so much for a presidential campaign. In order to get millennials to turn out, candidates must relate to and communicate with them directly, according to Hans Riemer, the national youth vote director for Obama for America from March 2007 to March 2008.

“What people are looking for is a candidate who is right on social issues, has an inclusive message, who understands the economic challenge facing young people and appeals to them, reaches out to them and says, ‘I want your vote. I need your support,’” said Riemer, now an at-large council member in Montgomery County, Maryland. “All three factors need to come into play.”

That’s partially why it’s so hard to forecast whether millennials will simply stay home if — and when — the race gets negative over the next few months.

Joe Slade White, a Democratic media strategist based near Buffalo, New York, who has worked with Vice President Joe Biden, said he thought the buzz around Sanders’ and Trump’s candidacy had already increased political engagement among youth. The fact that the election will likely be tight could also generate interest.

A large number of people may even head to the polls for the sole purpose of voting against Trump, whose divisive rhetoric White said could make him seem scary to young Americans. By November, White said he thinks young people will realize that “OK, we have a real choice, and this is an important choice, and therefore we’ll turn out.”

Alex Engelsman, the 19-year-old president of the Gettysburg College Independents in Pennsylvania, is paying attention to politics now, but he wasn’t always. Engelsman was in middle school in central Maryland when Obama was first elected, thinking more about which bands he liked than which candidate he backed.

When he did finally tune in, he found a dysfunctional Capitol where the Obama administration had to wrestle with the GOP for power. Engelsman, who grew up conservative, said that sort of extreme federal partisanship is all he’s ever known.

In trying to figure out his affiliation, he went to a College Republicans meeting, where Engelsman said he was “the most liberal person in the room.” Then he went to the College Democrats’ meeting, where he was “the most conservative person in the room.” That’s when he discovered he was an independent.

These days, Engelsman avidly follows all the candidates on Twitter and reads the Washington Post, Politico and Real Clear Politics to keep up with the news. He’s not sure who to vote for in November, but he definitely plans to participate because he doesn’t see any reason not to.

He can’t say the same for his peers, whom Engelsman acknowledged might get sick of the fighting in the upcoming months, especially because they're in a potential swing state.

“Young people want to go out and save the world. They want to think the world is amazing and the world they’re about to go into is a place that’s good and open to them,” he said. “And walking in and seeing that everybody just hates each other is never a good sign.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.