Ytterbium Atomic Clock: World’s Most Accurate Time Keeper That Can Run For Billions Of Years

A group of physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, or NIST, in the U.S. has developed a pair of atomic clocks, which they say are capable of keeping the most precise time ever for a period matching the age of the universe.

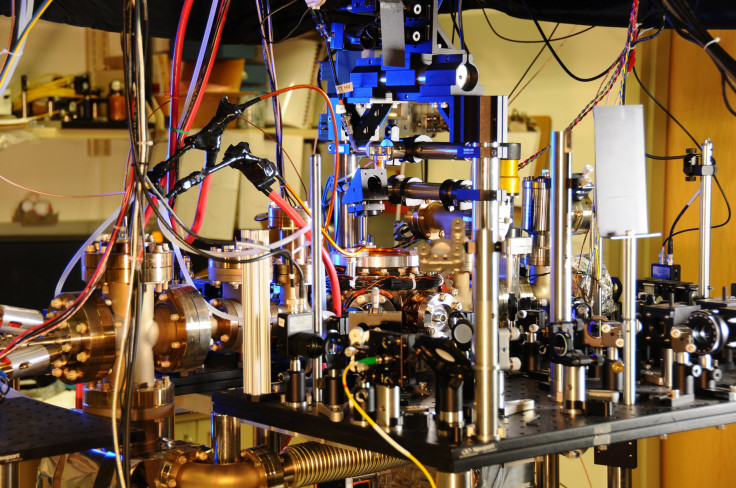

The new clocks, referred to as “ytterbium optical lattice clocks,” are said to have set a new record of stability, measured through the precision by which the duration of each tick matches that of every other tick.

The ytterbium clock’s ticks are stable to about one part in one quintillion (1 followed by 18 zeros), meaning the clock can calculate a second exactly the same up to the eighteenth decimal place, a feat that makes it about 10 times better than its predecessors, according to a NIST study, published in the journal Science Express on Thursday.

“The stability of the ytterbium lattice clocks opens the door to a number of exciting practical applications of high-performance timekeeping,” Andrew Ludlow, NIST physicist and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

According to researchers, the new ytterbium atomic clock can not only have a significant impact on timekeeping, but it can also help scientists test Einstein's theory of relativity more precisely to measure how time behaves differently depending on gravitational force. In addition, more accurate readings using the atomic clock could also prove valuable to enhance the performance of navigation, communication and global positioning systems.

Clocks make use of a mechanism called an oscillator, such as a pendulum, which changes in a regular way. In case of the ytterbium atomic clock, a laser light excites an electron in an ytterbium atom, which is the core of the system, and the excitation and de-excitation of the atom serves as a traditional pendulum.

Ytterbium -- a soft, malleable, ductile metallic element with a bright, silvery luster -- is denoted by the symbol Yb and atomic number of 70, and has potential applications in alloys, electronics and magnetic materials.

According to the scientists, the high stability of the ytterbium clocks helps achieve precise results very quickly. For instance, the current U.S. civilian time standard is NIST-F1 -- a cesium fountain clock -- which must be averaged for about 400,000 seconds (about five days) to achieve its best performance. On the other hand, the new ytterbium clocks achieve that same result in about one second of averaging time.

In 2011, one of Britain's cesium fountain clocks, responsible for keeping the country's atomic time, was declared as the world's most accurate long-term time keeper, after scientists evaluated the uncertainties of all the physical effects that could cause frequency shifts in the clock's operation, and observed that the clock would lose or gain less than a second in 138 million years.

In comparison, if the new ytterbium atomic clock were to have started functioning since the Big Bang -- about 13.8 billion years ago -- by now, it would be only off by one second, the Los Angeles Times reported, citing a physicist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.