Zika Virus In The US: How The Outbreak Became A Public Relations Mess

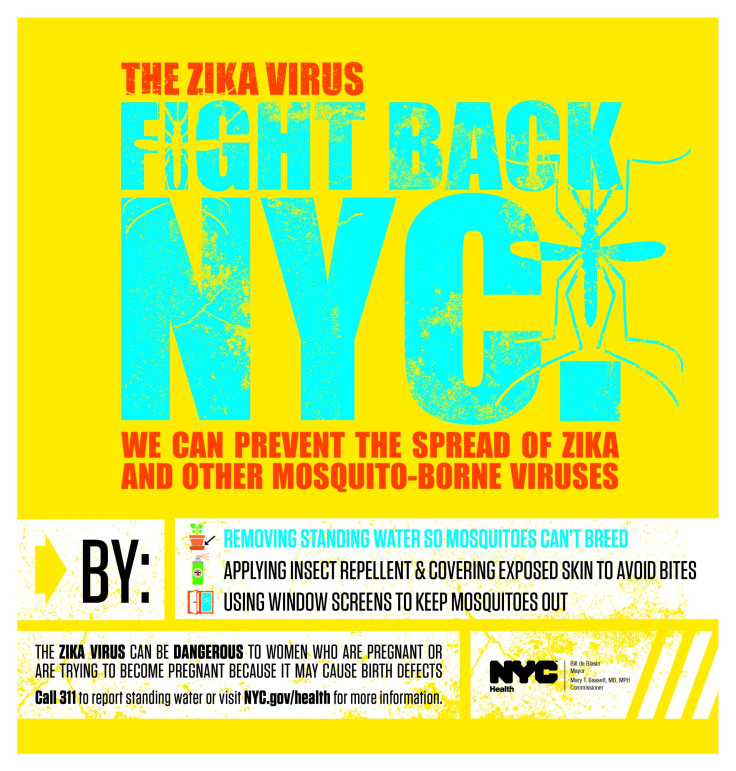

New York is in full mosquito-hunting mode. Armed with a three-year, five-borough, $21 million plan, New York City began gearing up in April to take on Zika virus-carrying Aedes mosquitoes. At the end of May, the state launched a “six-step action plan” that involved 100,000 tablets to kill mosquito larvae, plus bilingual public service announcements about the Zika virus for airing on more than 40 TV and 100 radio stations.

Some experts see this reaction as overkill, even as they stress the importance of simultaneously informing and reassuring Americans about Zika. The virus can cause devastating birth defects in babies, yet the majority of adults suffer no symptoms if they are infected. Communicating those risks accurately to a public informed by a fear-mongering media is a challenging, delicate endeavor. In New York, the response in many ways exemplifies the difficulties of explaining — and perils of mischaracterizing — the actual risks of Zika.

“Zika virus is certainly an imminent threat to Americans because the mosquito known to carry the virus — Aedes aegypti — is present throughout the southeastern United States,” said Josh Greenberg, an expert in crisis and risk communication. But the country was unlikely to see “an epidemic of babies born with severe birth defects, or adults who develop serious autoimmune disorders” at the level the outbreak has been depicted in the media, he added.

The epicenter of the Zika epidemic is in Brazil, where in March 2015 authorities first began noticing a mysterious illness. Cases have since spread to more than three dozen countries and territories in Latin America and the Caribbean. As of June 1, the United States had 618 reported cases, all travel-related. Of those, 130 cases, or more than 20 percent, were in New York.

So far, 195 pregnant women in the U.S. might have the virus, based on laboratory evidence suggesting a possible infection. If a woman contracts it while pregnant, Zika can cause microcephaly, a condition where infants are born with abnormally small heads and sometimes physical and intellectual disabilities.

For public health authorities trying to prevent the virus from spreading, these potential and devastating consequences raise the stakes considerably. Because Zika can be transmitted sexually, not just by mosquitoes, men and women alike who want to have children have to be careful. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has urged couples who are considering getting pregnant to take certain precautions, including simply waiting, if they think they’ve been exposed to Zika. For pregnant women, the agency recommends putting off travel to Zika-endemic areas.

Urging people to be proactive and protect themselves where and when appropriate, without stirring panic or exaggerating the risks, are part of a balancing act. The trouble with Zika is that lately, the balance has been off, risk communications experts say.

What most likely will happen with the Zika virus in the continental U.S. are small, local outbreaks, public health authorities at the CDC and the National Institutes of Health have said for months. The South, which is home to the Aedes aegypti mosquito that transmits the virus, is likely to be affected, especially its impoverished areas.

Upon hearing that people in 43 states had tested positive for Zika, some people began questioning whether they should even visit those states, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the NIH, noted in a blog post dated May 12. None of those cases had been acquired locally, however, so avoiding travel to a state with a reported case would do little to protect a person.

In that post, Fauci directly addressed the public relations challenges inherent in dealing with disease-related crises.

“We in the public health sector must be crystal clear in articulating exactly what we know and what we still need to know about the threat, and in helping people understand how this new risk compares to risks they willingly assume every day,” he wrote.

Yet this messaging can so easily slip from the public health sector’s control. In the media frenzy to cover the Zika virus, crucial nuances disappear, said Jody Lanard and Peter Sandman, a wife-and-husband risk communications team based in New York City.

“What’s not so well understood is there are places where Zika is likely to be bad. There are places where Zika is already bad. There are places where Zika is almost impossible. And then there are places in the middle,” Sandman said. “If you’re not a pregnant woman, or likely to become pregnant, your risk is very low,” he added.

Those discrepancies are one reason New York City’s anti-Zika campaign, which includes $1.2 million in ads, including bright yellow stickers plastered on the sides of garbage trucks, seemed excessive to Lanard.

“We are ... building the capacity to respond to every possible scenario, no matter how unlikely,” de Blasio said in April when the city rolled out its plan.

It was an “outrageously hilarious and exaggerated and alarmist statement,” said Lanard, who is also a physician. The alarm it raised was disproportionate compared to the actual risk to New Yorkers, yet the city would pour millions of dollars into the campaign nonetheless.

New York City’s anti-Zika effort sent conflicting messages to the public, Sandman said. One was that the city wasn’t going to have a big problem. The other is that the city would nevertheless react as if it did.

Media are at least partly to blame for these kinds of inconsistencies, experts said. Dramatic images of babies born with microcephaly have dominated Zika virus coverage in the mainstream media, often frightening viewers and playing an outsized role in educating Americans about the virus.

“These images have largely shaped our understanding of the virus and the risks it may pose,” said Greenberg. “Media coverage has been problematic,” he added, and photos of microcephalic babies have “no doubt clouded public understanding of the virus and the general threat.”

Social media also reinforce fears resulting from this kind of coverage, which can then inspire measures, proportionate or not, to protect the public.

“People look to certain people within their social network to validate information,” said Josh Michaud, an associate director with the global health policy team at the Kaiser Family Foundation, a Washington nonprofit focusing on health issues. If that information turns out to be wrong, “then you have a real recipe for disaster,” he added.

Correction, June 9, 2016, 4:29 p.m. EDT: A previous version of this story misspelled the last name of Jody Lanard.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.