Zombie Cancer Cells ‘Rescue’ Themselves Before Death, May Complicate Chemotherapy Treatments

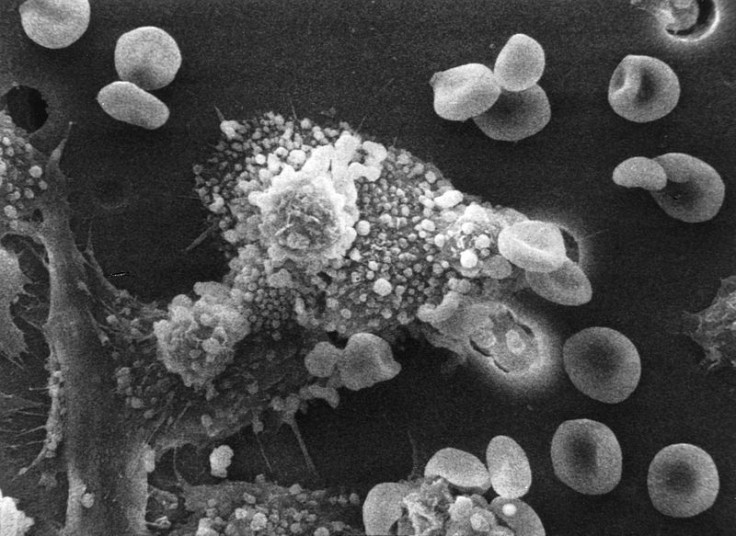

Like zombies returning from the grave, certain cancer cells might be able to overcome death even after being destroyed by chemotherapy, according to new research.

Normal cells routinely undergo a process called autophagy during which a cell “eats” parts of itself that have become obsolete. It’s a kind of cellular system of recycling. Cells isolate and decompose unnecessary components, allowing them to turn waste into energy and thereby ensuring cellular survival during starvation or times of stress.

It’s a nifty endurance tactic for healthy cells, but a dangerous mechanism in cells that are cancerous. Researchers from the University of Colorado Cancer Center found that autophagy may allow tumor cells to return from the dead.

Scientists working with a chemotherapy drug known as TRAIL noticed that when tumor cells’ mitochondrial walls began to break down -- a sure sign of cell annihilation -- a period of elevated autophagy kicked in during which the tumor cells actually began to recover the mitochondrial proteins they had shed. They used the salvaged pieces to restore the cells’ functions and even went on to divide and reproduce.

"What we showed is that if this mechanism doesn't work right, for example if autophagy is too high or if the target regulated by autophagy isn't around, cancer cells may be able to rescue themselves from death caused by chemotherapies," Andrew Thorburn, deputy director of the center, said in a statement. "The implication here is that if you inhibit autophagy you'd make this less likely to happen, i.e. when you kill cancer cells they would stay dead.”

The study, published in the journal Cell Reports and presented at the American Association for Cancer Research conference on Saturday, noted that autophagy can control apoptosis, the process of programmed cell death.

"Many chemo therapies also can kill by necrosis and we don't know if we would skew the death mechanism [toward necrosis] by inhibiting autophagy," Thorburn told Vice Motherboard. "With TRAIL it doesn't seem so. We just get more tumor cell death by increasing apoptosis. However if it happened with other drugs it could be a good thing because there may be benefits to getting a more necrotic type of death."

Motherboard notes that encouraging cells to die by necrosis, the process of a cell dying haphazardly rather than by a programmed process, also has its setbacks. When cells die and are not recycled, they end up becoming junk in the body that builds up and rots, the outcome of which is gangrene.

"Autophagy is complex and as yet not fully understood," Thorburn said. "But now that we see a molecular mechanism whereby cell-fate can be determined by autophagy, we hope to discover patient populations that could benefit from drugs that inhibit this action."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.