100 Years After Armenian Genocide, Lebanon’s Armenians Demand US Recognition, Apology From Turkey

BOURJ HAMMOUD, Lebanon -- Vrej DerVarhanian’s right arm is tattooed with the Armenian flag and his left with a cross, two symbols that tell his family’s history without words. One hundred years ago, his great-grandmother walked from Armenia to a Christian town in what is today Syria, to escape the Ottoman Turks' slaughtering of her people. She was 11 years old, orphaned by war, and had to make the brutal journey with four of her younger siblings. She made it. She then started a family and eventually settled near Beirut, on a parcel of land that would become today's Bourj Hammoud district, where Armenians fleeing the massacres set up a condensed version of their homeland.

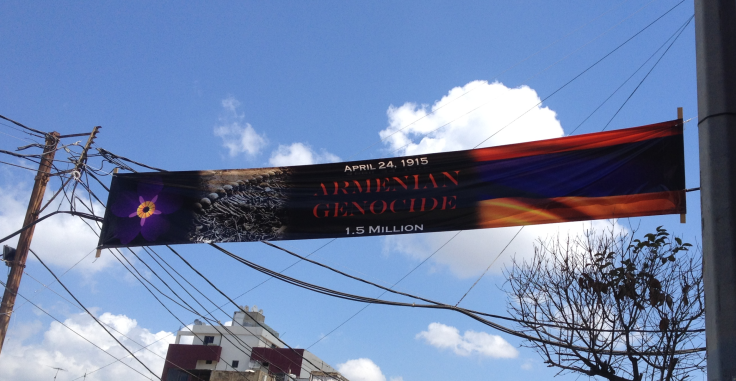

Friday marks the 100th anniversary of the Armenian massacre that left 1.5 million people dead. Stories like that of DerVarhanian’s great grandmother’s are many, and though they are passed down to every generation of Armenians, not everyone in the international community recognizes the massacre as a genocide. The United States, for one, does not, and people in this majority-Armenian community of 150,000 are incensed. On Wednesday, President Barack Obama avoided using the word “genocide” to describe the 1915 atrocities against Armenians, leaving many in Bourj Hammoud feeling like the biggest world power had once again ignored them.

In honor of the anniversary on Friday, most businesses and roads in the Armenian district will be closed. Time has not thawed feelings toward the Turkish government. While most of Beirut is covered in different politically influenced graffiti, nearly every street in the Armenian district bears the same spray-painted accusation: "Turkey Guilty of Genocide."

Many here believe the U.S. should lead the international community in recognizing the atrocities as a genocide. But Obama has been consistent in his omission of the term “genocide” since becoming president, a sharp change from his rhetoric during his time as a senator and presidential candidate. The decision not to label the killing of Armenians a genocide again this year came after more than a week of debate between top U.S. officials. Turkey says the Ottoman Empire did not commit genocide and that the number of dead is smaller than the 1.5 million agreed upon by historians.

Obama "is the key of the solution,” said Kevork Kazanjian, a Lebanese-Armenian convenience store owner in Bourj Hammoud. His advice to the president is to “be a man."

Some Congress members disagreed with the Obama administration’s decision. But the U.S.’s relationship with Turkey, both a NATO ally and a crucial partner in the fight against the Islamic State group, looms large over any debate between Washington and Ankara on the issue, and this alliance was not lost on Armenians in Bourj Hammoud.

“It’s wrong. America is the biggest country in the world; they should recognize this,” said Crist Bedrasian, a Syrian-Armenian who works at a café here. “Something is going on between the U.S. and Turkey.”

Recognition for the atrocities of 1915 remains essential for most Armenians. Some still hold out hope that with the label of genocide will come the ability to return to the land where Armenians lived under the Ottoman Empire, most of which is now a part of modern Turkey, but most who have settled in Bourj Hammoud simply want the truth to become a part of history.

“After 100 years, I don’t think we’re going to get the land back,” said Kazanjian. "But for once in their life, they will say they’re sorry for what they did to our grandfathers.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.