2012 Year In Review: The GOP Became An Epic Failure, Marching Itself Into A Corner

With an interminable campaign filled with negative ads, 2012 was definitely the year for politics in the United States. The election cost an estimated $6 billion, there were huge numbers of early voters and youth votes, and at the end of it all, President Barack Obama secured four more years in office and the Democrats gained ground in Congress.

It was also, arguably, the year the GOP became an epic failure. The Republicans have fallen into chaos since the election, with their House majority serving only to humiliate their own speaker during fiscal talks with the White House. Their brand is in ruin, culminating last week with the party disregarding the vast majority of the population just to protect 0.3 percent of the population from a tax hike that may go into effect due to the fast-approaching fiscal cliff. This comes even as dozens of millionaires and billionaires have been practically begging the government for months to take their money.

Days after defeating Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney, Obama said he was ready to work with Congress to pull the nation away from the so-called fiscal cliff, the collection of federal tax increases and spending cuts set to take effect on New Year's Eve if no action is taken. The aim is to slash approximately $500 billion from the federal budget deficit.

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has warned that the double whammy of tax increases and spending cuts -- about 4 percent of GDP -- could plunge the already fragile economy back into recession and raise unemployment in 2013 if Washington doesn’t act in time.

Immediately after Obama’s re-election, it seemed as if Republicans had learned from their defeat. Some of their leading governors expressed concerns that the GOP was viewed as the protector of loopholes for big businesses, Wall Street and the richest among us.

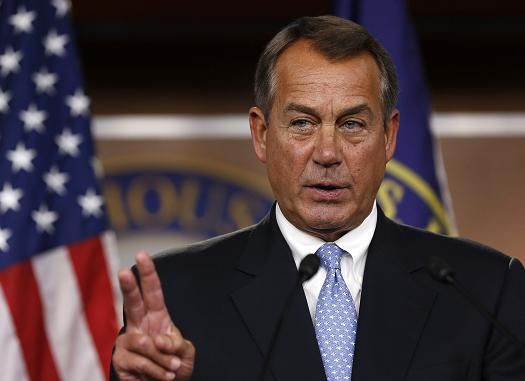

It appeared as if changes were ahead. Obama even threw out the word “compromise” more than once (and reminded Republicans that the people re-elected him because they agree with his approach). House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, said he was ready to talk with the White House. He was adamant that “2013 should be the year we begin to solve our debt through tax reform and entitlement reform.”

To steer America away from the impending fiscal pileup, Obama's opening bid was $1.6 trillion in new revenue over a decade through taxing the wealthy and corporations. He defined the wealthy as single taxpayers earning more than $200,000 annually and couples with an annual income of more than $250,000, equaling some 2 percent of the population, and he pressured Republicans to preserve the George W. Bush-era tax cuts for everyone else.

To Republicans, it looked as if the president wasn’t there to make a deal and was overplaying his hand. After all, just last year Republicans offered to raise $800 billion over the next decade by rewriting the tax code, and now the asking price had doubled.

Approximately two weeks into the negotiations, Boehner told the nation that no significant progress was being made. He proposed a counter-offer to raise $800 billion in revenues. This money would most come from closing unspecified loopholes and deductions for the wealthy. But Republicans weren’t budging on their stance against a tax rate increase for any income level, and Obama wasn't about to accept any proposal without a tax increase.

Positioning was stifling the talk. The public could only watch with uncertainty about whether a deal could be struck in time.

Showdowns like this were not uncommon between Democrats and Republicans. The fiscal cliff negotiation was almost a replay of the debt-ceiling debacle last August, where America’s ability to meet its financial obligations was cast in doubt. Ultimately, Standard and Poor’s did the unthinkable and downgraded the U.S. credit rating.

As the year-end deadline approached, a CNN/ORC International poll found that a majority of Americans thought the Republican Party's policies are too extreme. Fifty-three percent of the population wanted the GOP to compromise more in finding bipartisan solutions to the nation's fiscal problems. Only 41 percent felt the same about Democrats.

"That's due in part to the fact that the Republican brand is not doing all that well," CNN polling director Keating Holland drew from the survey.

The public also didn't have much confidence in Boehner. The CNN poll found he had only 34 percent of the public's approval compared with Obama's 52 percent.

Still, the will to shift into second gear and begin pulling away from the cliff was visible in mid-December when the president made some concessions. Obama raised the tax increase threshold to $400,000 and proposed cost-of-living formulas that would lead to cuts in Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid.

Things were in motion now, or so the nation thought. A cunning Boehner was planning a detour. His gambit was “Plan B,” a two-part measure. The first was a conservative-skewed spending cut that narrowly got House approval last Thursday, and a tax increase only on those earning $1 million or more annually. It was Boehner's back-up plan to protect as many Americans as possible from the fiscal cliff tax hikes. “Plan B” was his way of saying the Republicans care about the 99.7 percent of the country who would keep their tax break next year.

“I think we all know that every income tax filer in America is going to pay higher rates come Jan. 1 unless Congress acts,” Boehner said. “So I believe it’s important that we protect as many American taxpayers as we can. Our Plan B would protect American taxpayers who make $1 million or less, and have all of their current rates extended.”

Even though powerful anti-tax lobbyist Grover Norquist issued a convoluted ruling that “Plan B” would not a violate his famous no-tax pledge, the bill was dead before it arrived on the House floor. House Republicans stood by the 0.3 percent, forcing Boehner to pull the bill because of a lack of support, sending the caucus home for the Christmas holiday.

“Now it is up to the president to work with Senator [Harry] Reid on legislation to avert the fiscal cliff,” he said last week. “The House has already passed legislation to stop all of the Jan. 1 tax rate increases and replace the sequester with responsible spending cuts that will begin to address our nation’s crippling debt. The Senate must now act.”

Boehner’s efforts to back Democrats into a corner failed. If any thing, “Plan B” damaged him, showing him as someone with little power and as someone who cannot deliver on deals.

“Plan B’s” failure begs the question “Who’s running the show in the House?” said Thomas Whalen, political historian at Boston University.

Whalen even expects Boehner’s resignation soon.

“I just don’t see him surviving,” he said. “You want a speaker who can get things done and cut deals with the White House. He is a bad legislator and he needs to go.”

Of course, with only seven days to go in 2012, Boehner himself doesn’t know what’s about to happen next. He said, “God only knows.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.