2012 Year In Review: Major Worker Strikes - Looming US Port Strike, Violent South African Mine Strike And More

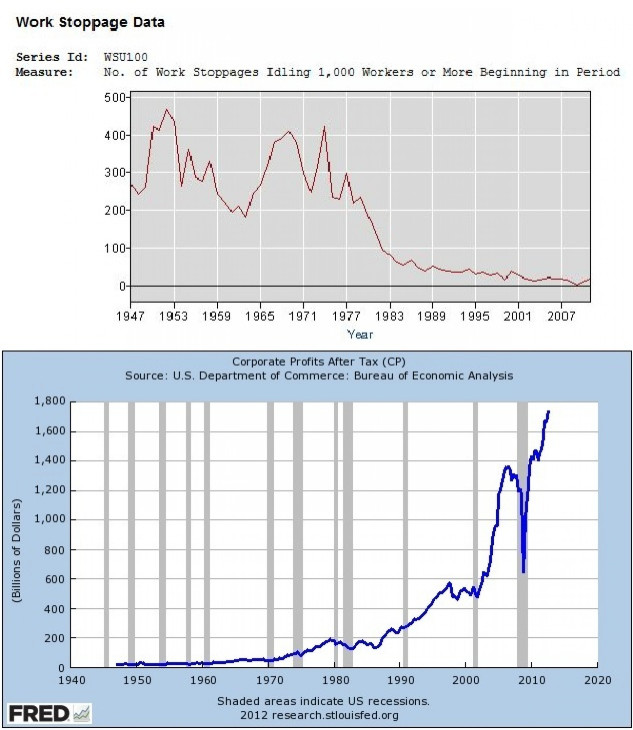

Work stoppages, once a mainstay of the labor arsenal, have fallen off precipitously since the early 1980s. Over the same period, perhaps not by coincidence, corporate profits have mostly risen even as inflation-adjusted wages have remained stagnant.

Hence, a recent spate of high-profile strikes, including by Chicago teachers, non-unionized Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (NYSE: WMT) workers and New York City fast-food employees, has some experts wondering if we're seeing a resurgence of the tactic.

A look at some of the major worker walkouts in 2012:

1. “Container cliff”: East Coast faces “devastating” port strike:

A potential strike by thousands of dock workers from Boston to Houston threatens to cripple U.S. commerce as early as this weekend.

At issue is a labor dispute between the International Longshoremen's Association, which represents dock workers, and the U.S. Maritime Alliance, which represents port operators and shipping companies.

In a last-ditch effort to avert a strike, both sides agreed to meet one more time before the expiration of their contract extension at midnight Saturday. No date or place for the meeting was announced. If the sides fail to extend the negotiations or reach an agreement, 14,500 workers at the 15 ports -- including the 4,000 dockworkers in New York and New Jersey -- could walk off the job on Dec. 30. The last time there was an East Coast longshoremen's strike was back in 1977.

The New York-New Jersey port, which handled cargo valued at $208 billion last year, is the largest port on the East Coast and is the second-largest to handle manufactured goods from China.

The other ports that would be affected by a strike are Boston; Delaware River; Baltimore; Hampton Roads, Va.; Wilmington, N.C.; Charleston, S.C.; Savannah, Ga.; Jacksonville, Fla.; Port Everglades, Fla.; Miami; Tampa, Fla.; Mobile, Ala.; New Orleans and Houston.

Any supply chain disruption at the ports would immediately affect every importer and exporter – potentially disrupting or delaying spring and summer retail merchandise – that uses the facilities.

Business groups and state officials warn it could cost billions, citing estimates that a 10-day port lockout in 2002 cost $1 billion a day -- and caused a major backlog in shipments.

The key sticking point is container royalties, which are payments to union workers based on cargo weight. Port operators and shipping companies want to cap the royalties at last year's levels to stay competitive. They believe the royalties have become a huge expense unrelated to their original purpose and amount to a bonus averaging $15,500 a year for East Coast workers already earning more than $50 an hour. The longshoremen's union says the payments are an important supplemental wage, not a bonus.

The strike would come on the heels of a separate labor action that temporarily shut down ports on the West Coast. Earlier this month, striking harbor clerks reached a tentative deal with management at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach after an eight-day labor clash.

The strike cost Southern California an estimated $8 billion, including lost wages and the value of cargo rerouted to other ports.

2. Union strike leads to shutdown of Twinkies maker Hostess:

Hostess Brands Inc. filed for its second Chapter 11 bankruptcy in less than a decade this January, citing steep costs associated with its unionized workforce.

The company was able to reach a new contract agreement that would slash workers’ pay benefits with its largest union, the Teamsters. But the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union, whose members constitute about one-third of Hostess' nearly 18,000 employees, rejected the terms and went on strike on Nov. 9.

A week later, the Twinkies, Ding Dongs and Ho Hos maker declared that it had to liquidate, saying the strike crippled its ability to maintain normal production.

The 82-year-old company received approval from a federal bankruptcy judge to give its top executives bonuses up to $1.8 million as part of its wind-down plans. Hostess said the incentive pay is needed to retain the 19 corporate officers and "high-level managers" during the liquidation process, which could take about a year.

On Dec. 21, the Irving, Texas-based Hostess said in bankruptcy court that it’s narrowing down the bids it received for its brands and expects to sell off its snack cakes and bread to separate buyers.

The liquidation of Hostess ultimately means the loss of about 18,000 jobs, not including those shed in the years leading to the company's failure.

2. Chicago teachers’ strike, first of many challenges ahead for Mayor Rahm Emanuel:

Chicago’s nearly 30,000 teachers walked out on Sept. 10, when negotiations broke down after months of talks. Among the major issues, the teachers are negotiating over the length of the school day, objecting to their evaluations being tied to performance and fretting about potential job losses.

The Chicago Teachers Union agreed on Sept. 18 to end its seven-day walkout in the nation’s third-largest school system, allowing some 350,000 public school students to head back to class.

The first Chicago teachers' strike in 25 years turned a spotlight on rising tensions nationally over teachers’ circumstances.

Although the grueling teachers strike is over, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel still faces many daunting tasks as he pushes ahead on his promise to reform the city's underperforming classrooms.

4. Wal-Mart workers push back on Black Friday:

Hundreds of protesters, including some Wal-Mart workers who skipped their shifts on Black Friday, protested for the right to speak up to managers about wages, hours and benefits.

OUR Walmart, an organization backed by the United Food & Commercial Workers union, said it counted 1,000 protests in 46 U.S. states, including strikes in 100 cities -- figures that Wal-Mart said were "grossly exaggerated."

Wal-Mart countered that it had its best Black Friday ever and that the majority of protesters were not its employees.

5. Fast-food workers in New York demand better pay:

In late November, hundreds of workers from fast-food outlets across New York City went on strike, demanding higher wages and recognition for a new union called the Fast Food Workers Committee.

Workers from McDonald's Corporation (NYSE: MCD), Wendy’s, Taco Bell, KFC, Domino's Pizza, Inc. (NYSE: DPZ), and Burger King demanded $15 an hour in pay -- a step up from the minimum wage many employees currently earn.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, fast-food work is the lowest-paying occupation in the U.S., and the median salary for a fast-food worker in 2010 was $18,130 a year -- meaning that the average fast food worker in 2010 was at exactly the federal poverty line for a family of three.

6. AT&T workers strike over health care, job protection

About 20,000 AT&T Inc. (NYSE: T) workers in California, Nevada and Connecticut went on strike in August, accusing the company of unfair labor practices.

At issue in the negotiations are job protection clauses and health care premiums and co-payments. AT&T says it wants employees to shoulder more of their growing health care costs and wants more leeway to downsize its shrinking landline operations. Some of its workers have contracts that guarantee them job offers at different parts of the company if they're laid off.

AT&T said in a statement that its workers have "high-quality middle-class careers with wages and health care benefits that are among the best in the country."

7. Mine protests turn deadly in South Africa:

A wave of strikes swept South Africa's gold and platinum mining industries this year. The labor unrest has rattled investors in the continent's largest economy and has claimed the lives of more than 50 people, including 34 shot dead by police in one incident in mid-August near a mine operated by platinum producer Lonmin Plc (LON: LMI).

Around 80,000 South African miners or 15 percent of the workforce had been off the job at one point. Even though the majority of strikes have ended, the deals made between workers and the companies are on shaky ground, meaning South Africa's crucial mining industry may face more strikes.

The International Monetary Fund forecasts South African gross domestic product growth of 2.6 percent this year and in October cut its 2013 growth forecast to 3 percent from a July projection of 3.3 percent. The uncertainty risks further damage to Africa's largest economy and could lead to more job losses in a country where unemployment already sits at 25 percent.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.