3D-Printed Hearts From Human Fat Cells? Scientist Says ‘Bioprinting’ Organs Possible ‘In 10 Years’

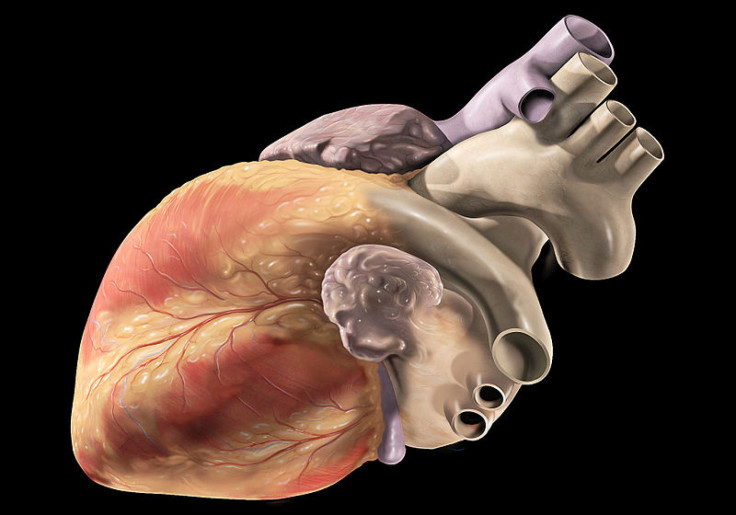

Science is paving the way for doctors to create 3D-printed hearts and other organs using technology similar to that of 3D printers. “Bioprinting,” in which a doctor uses a patient’s own body cells to reconstruct an organ or even part of an organ, is no longer a thing of science fiction. Scientists say the ability to 3D-print fully functional organs is only about a decade away.

"For bioprinting it is the end of the beginning as bioprinted structures are now under intense study by biologists," Stuart Williams, executive and scientific director of the Cardiovascular Innovation Institute in Louisville, Ky., told Wired. "Dare I say the heart is one of the easiest to bioprint? It's just a pump with tubes you need to connect. A kidney is much more complex. And then the brain …"

Wired reported that Williams is a leader in the field of 3D printed organs. Williams and his team are working with biologists to figure out how they can bioprint an entire heart from a person’s fat cells. He says the goal is to be able to print a heart in under three hours, and then allow the heart a week to grow before splicing it into a patient’s body. The process actually isn't as complicated as it sounds.

"You take tissue from a patient isolate the cells, because we're all made up of just billions and billions of cells put those cells into a machine, hit a button and it will print out a heart," Williams told Kentucky’s WDRB radio station earlier this year. “Fifty CCs of fat is two golf ball size pieces of fat and there are enough cells in that fat to rebuild basically all of the major blood vessels in the heart.”

Williams explained that some of the parts of the heart, like the blood vessels and the valves, would need to be assembled separately.

Bioprinting entire hearts certainly sounds far off, but it’s actually not all that novel. USA Today reports that scientists have been experimenting with 3D printing human organs since the 1990s. Three-dimensional bioprinting, like other forms of 3D-printing, involves using a medium -- in this case, cells inside a biologically safe glue -- to add layer on top of layer to create a complete structure. With bioprinting, the glue eventually dissolves inside the body, much like surgical sutures.

"Bioprinting is pretty much done everywhere," Anthony Atala, director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina, where scientists won an award for innovations in bioprinting earlier this year, told USA Today in May. "Our ultimate goal is increasing the number of patients who get organs."

But creating 3D-printed hearts isn’t an easy feat. One of the major difficulties with bioprinted organs is keeping it alive. As Discovery noted, scientists will have to figure out how to create the intricate network of tiny blood vessels that keep organs healthy. Currently, 3D printers can only print objects as small as a few millimeters, but some of the smallest blood vessels have widths of just a few microns -- or one-1,000 of a millimeter.

The other issue is money. Bioprinting is expensive, and will require funding for more research and development.

"The foundations of the project are solid but there needs to be rapid progress in printing of such a complex tissues, in creating enough cells to print and in the maturation of the final tissue,” Kevin Shakesheff, director of the Wolfson Centre for Stem Cells, Tissue Engineering and Modelling and the UK Regenerative Medicine Platform Hub in Acellular Technologies, told Wired. "There is great interest and support [because] everyone understands this technology will lead to ancillary discoveries and new therapies."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.