The 4th Of July: An Obscure History; Who Did What, When And Where, On Or Around Independence Day

As everyone knows, this week we celebrate the popular Aphelion holiday. No? Well, July 4 (or thereabouts) is not only Independence Day; it’s also when the Earth is at its farthest point from the sun. Every planet has an aphelion, and ours coincidentally falls around the anniversary of American independence, which is also (counterintuitively) our hottest holiday.

The fact that we’re swinging wide through the universe may explain why a great many other momentous political divorces have occurred around this time. In addition to the anniversary of American independence from England in 1776, the long holiday weekend is also a time to celebrate (or, maybe, protest) the Philippines’ independence from the U.S. (July 4, 1946) and, on July 5, Venezuela’s independence from Spain (1811), Algeria’s from France (1962) and Cape Verde’s from Portugal (1975).

Which means that if you’re looking for an alternative to the traditional Fourth of July pastimes of swimming, grilling, parading, setting off minor explosions -- or if it rains -- you could justifiably curl up with the remarkable 1966 Algerian film “The Battle of Algiers.” Or if that’s a bit too weighty, perhaps you’d prefer to watch a marathon of “Green Acres.” (Eva Gabor, who starred in the quirky 1960s comedy, died on July 4, 1995.)

For further celebrations and commemorations, we offer the following obscure history of this weekend. We begin on July 4, A.D. 414, when Roman Emperor Theodosius II, age 13, yielded power to his older sister Aelia Pulcheria, who proclaimed herself Empress Augusta of the Eastern Roman Empire. As a reminder, this episode was real and affected millions of Roman subjects; it was not a backyard play in which Aelia dressed up her little brother in their mother’s house dress and forced him to abdicate again and again to the delight of her friends.

Fast-forwarding to 1754, George Washington had a particularly bad Fourth of July, though at that point he had no idea that the date would become sacrosanct in the United States, because there was no United States. Instead, 20-plus years before independence, the Fourth was best known for the routing of Washington’s troops from Fort Necessity by hostile French and Indian fighters at the start of the eponymous war. The fort was looted while Washington and his troops hurried away, beating drums and waving flags. If you’re on the East Coast or in the Rust Belt, you could drive over to the site of Fort Necessity, which is now a national historical park about an hour and a half from Pittsburgh.

Next, the obvious: 1776. This is the most famous July 4 event, though not, as some of you “non-history buffs” may believe, because the Pilgrims and Indians gathered on this date to shoot off fireworks at Plymouth Rock. It was instead the signing in Philadelphia of the Declaration of Independence, copies of which were dispatched the next day to various colonial bigwigs and Continental troop commanders, all of whom no doubt made a big show of having received personal signed copies, unlike their neighbors.

It’s not known how the D-of-I signers celebrated the 4th, but if the drafting of the U.S. Constitution on Sept. 17, 1787, is any indication, there was a big blowout. After wrapping up work on the Constitution, those 56 signers reportedly put away 54 bottles of Madeira, 60 bottles of claret, eight bottles of whiskey, 22 bottles of port, eight bottles of hard cider, 12 beers and seven bowls of alcoholic punch, according to drunkard.com.

Chronologically, the next notable July 4 event was the birth, in 1810, of P.T. Barnum in Bethel, Conn. Variously described as a showman, music promoter, scam artist and significant employer of freaks, Barnum is famous for his promotional hoaxes and the creation of what came to be known as the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, the reputation of which was sullied on July 6, 1944, by the Hartford Circus Fire, also in Connecticut, when an estimated 100 people died inside a flaming tent. Afterward, several neglectful circus execs went to jail. The moral of the story: Do not even think of setting that off inside.

Next, in what is doubtless among the strangest historical coincidences, both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams conveniently died on July 4, 1826, on the 50th anniversary of the signing -- their signing -- of the Declaration of Independence. It seems almost too perfect, right? Newspaper editors looking for a holiday hook were lucky that year.

Jefferson was buried on July 5 at his Monticello home in Virginia. Adams, Jefferson’s political rival, who had lost his presidential re-election bid to Jefferson in the bitter campaign of 1800 and had been “too depressed” to attend his foe's inauguration, was buried two days later, on July 7. The groundbreaking document was said to be partly Adams’ idea, and he had served on the committee that drafted it for God’s sake, yet the only tombstone that reads “Author of the Declaration of Independence” is Jefferson's.

The pair made up in their later years and exchanged some of the most stunningly literate letters in American history, covering politics, religion, governing and philosophy. With his final breath, Adams uttered, “Thomas Jefferson survives.” He was wrong; Jefferson had died hours earlier.

Adams was likewise a few days off when it came to the holiday itself. He had predicted that everyone would go with July 2, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution to draft the declaration. In a letter to his wife, he wrote, “The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

Oh, well.

Though not a signer -- he was only 18 at the time -- fellow Founding Father and President James Monroe died on July 4, 1831 -- the third president in a row to die on the anniversary. No doubt all other living presidents since have exercised extreme caution on the Fourth of July; no one needs that kind of footnote. As an aside, four decades later, on July 4, 1872, future president Calvin Coolidge was born.

Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” was self-published on July 4, 1855. The famous poet is said to have designed and even typeset parts of the book, and though it did not originally bear his name, his boss, the secretary of the interior, fired him anyway (“Everybody knows you wrote it, Whitman -- we’ve all heard that story about the Brooklyn ferry”) due to the sensuous nature of the poems. Whitman spent the rest of his life revising and adding to the book, including on his deathbed. More than a century later, Bill Clinton reportedly gave copies to both Hillary and Monica Lewinsky, in separate yet uncomfortably related episodes.

Also published on July 4, in 1865, was “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” For that, feel free to let your imagination run wild in coming up with commemorative activities, and please do report back.

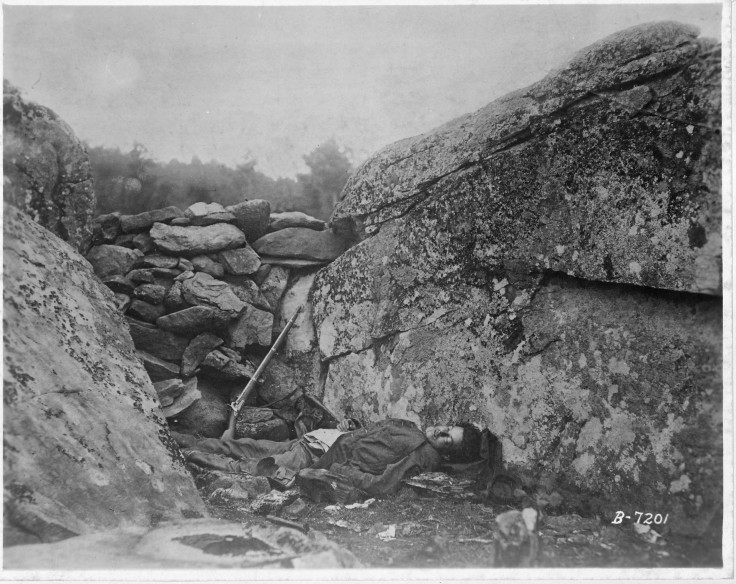

On the July 4 battlefield circuit, two fateful events occurred in 1863: The fall of the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Miss., after a 47-day siege, and the defeat of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg, Pa. Officially, Vicksburg did not again celebrate the Fourth of July until the nation’s Bicentennial in 1976, though some historians point out that there have been infrequent celebrations over the years. The surrender of Vicksburg was the culmination of one of the most brilliant military campaigns in history, by Gen. U.S. Grant, during which more than 10,000 Union and 9,000 Confederate troops were killed or wounded.

Fun fact: On July 5, 1863, as Grant and his entourage were touring battle-scarred Vicksburg, looking for the perfect mansion to occupy, one of his captains noticed a young woman on the front steps of a particularly nice one (25 rms, riv view) making ugly faces at them. Naturally they chose her house to co-opt, and as the soldiers entered, she and her friends “fled like a flock of partridges,” according to one account. When Grant eventually departed, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman had the house reduced to rubble.

In the Eastern theater, Lee’s army spent the holiday retreating from Gettysburg, providing famous war photographer Mathew Brady with countless grisly photos, including some he is believed to have staged. The two armies had together suffered about 50,000 casualties, and historian Bruce Catton wrote that the town “looked as if some universal moving day had been interrupted by catastrophe.” In addition to thousands of dead soldiers putrefying in the summer sun, the post-battle horrors included the burning of more than 3,000 horse carcasses in very stinky bonfires outside of town. No fun commemorative op there.

Not to change the subject, but for some reason, the nation of Western Samoa decided in 1892 to unilaterally move the international dateline, thereby creating a special 367-day calendar that year, which included two successive Mondays, both Fourths of July, which sets the record for the longest holiday weekend.

Continuing our military tour, two World War I-related events took place around the 4th, if you count the dates recorded on something called the Julian Calendar, which is necessary for our purposes here. Ninety-nine years ago last weekend, Archduke Franz Ferdinand paved the way for WWI and later the indie-rock band of the same name when he and his wife, Sophie, were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Ferdinand, who was wearing a green plumed hat at the time, had, earlier in the day, personally deflected a grenade tossed at his open car; the grenade exploded and injured numerous parade-goers. This was the first hint that things weren’t going to go well that day. For some reason, accounts of the date of the couple’s interment in their crypt (encryption?) vary, with some giving it as July 2 and some July 4.

Similarly, the only way to shoehorn the execution of Tsar Nicholas II and his family into the weekend is to rely on the Julian calendar. According to that obscure timekeeper, on July 4, 1918, the absurdly handsome Russian Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, daughters and a small group of faithful servants were executed by the Bolsheviks. (The “regular calendar” puts it on July 17.) At the time, Nicholas was worth about $300 billion in today’s dollars; his daughters were shot and stabbed numerous times supposedly because it was difficult to kill them as they had inadvertently armored themselves with 1.3 kilograms of diamonds and other precious gems that were sewn inside their clothing. None of which explains why the Russian Orthodox Church, which canonized the whole family, still goes by the Julian calendar.

Sandwiched between these WWI-related events, American sisters Adelina and Augusta Van Buren set out on July 4, 1916, on the first successful transcontinental motorcycle tour by two women. Part of their mission was to convince the military that women were fit to serve as dispatch riders, and according to some accounts, they were arrested numerous times along the way for wearing men’s clothes. In hindsight, it is hard not to relegate the episode to the category of all-too-common holiday publicity stunts/ego trips.

Which leads us to July 5, 1946, when the first bikini debuted at a poolside fashion show in Paris. So daring was the skimpy ensemble that designer Louis Reard had a hard time persuading a woman to model it for the cameras, though he eventually found an eager taker in the comely form of Casino de Paris showgirl Micheline Bernardini. Inexplicably, Reard named the bathing suit after the Bikini Atoll, an island in the Pacific Ocean that had been the site of a U.S. atomic bomb test earlier in the week. On second thought, perhaps “tiny” + “the bomb” makes a kind of sense. European women had been wearing comparatively modest two-piece bathing suits since the 1930s (for that matter, a Roman mural depicts an ancient version), and American women had embraced the fashion during World War II, but the more risqué style was considered a response to the sense of liberation that followed the war’s end; it wasn't until the early 1960s that the truncated style caught on in comparatively conservative America.

Reacting to a competing designer’s truncated two-piece that was billed as “the world’s smallest bathing suit,” Reard described the bikini as “smaller than the world’s smallest bathing suit.” As the popularity of the bikini spread, Spain and Italy passed laws prohibiting the suits on public beaches, though by then there was no turning back.

In a similarly revelatory vein, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Freedom of Information Act on July 5, 1966, providing U.S. citizens access to public documents and acknowledging that dead news days provide opportunities for grabbing headlines. Five years later on the same day, President Richard M. Nixon signed the Twenty-sixth Amendment to the Constitution, lowering the voting age from 21 to 18.

Conversely, the likelihood that few people will pay much attention to newswires around the 4th has made Independence Day a perfect time for businesses to release information they don’t want shareholders to hear. Apple did this a few years ago when the computer maker chose July 5 to reveal that lawsuits had been filed against the company for backdating stock options. (Apple also opted to report that Steve Jobs was taking a medical leave on Martin Luther King’s birthday, when the stock market is closed.)

In at least one case, a technology firm tried to minimize the damage from a big earnings shortfall by making the announcement at 12:01 a.m. July 4 (33 hours before the market would reopen). The bury-the-bad-news strategy didn’t work. When the market resumed, the company’s stock plunged to $21.63 from $29.50, obliterating $12.7 billion of its total market value.

Although it’s not clear where this fits into the slow news day paradigm, on July 5, 1989, Oliver North was sentenced to a three-year suspended prison term, two years of probation, $150,000 in fines and 1,200 hours of community service for his role in the Reagan-era Iran-Contra Affair. The convictions were later overturned.

On the celebrity front, there have been numerous births and deaths around this time. Geraldo Rivera entered the world on July 4, 1943, and in addition to Gabor in 1995, Charles Kuralt died on July 4, 1997. Dolly the Sheep became the first mammal cloned from an adult cell on July 5, 1996. Also, last year Kim Kardashian updated her chronicle of the decline of Western civilization by posting some awesome photos on her website taken “a few years ago” of her and her friends watching July 4 fireworks from a boat on the Hudson River.

And speaking of life and death, on July 4, 1999, President Bill Clinton imposed trade and economic sanctions against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan -- fixing that little problem, once and for all.

Finally, last year, the official Fourth of July trailer was released for the not-surprisingly extremely violent video game "Assassin’s Creed III," which is set before, during and after the American Revolutionary War, with a soundtrack that includes a song from a metal album called … Aphelion.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.