After Gas Leak Tragedy, Bhopal Victims Fall Prey To Virus

Victims of a horrifying 1984 gas leak in the Indian city of Bhopal, who have long suffered the debilitating fallout of the world's worst industrial disaster, are now dying from coronavirus, with relatives and activists accusing the government of abandoning them and withholding treatment.

Toxic methyl isocyanate released from the Union Carbide pesticide factory killed 3,500 people in the central Indian city immediately and 25,000 more in the years that followed.

Now its victims make up a significant proportion of coronavirus fatalities in Bhopal -- at least 20 out of 45, according to government data, while activists say 37 of the dead suffered illnesses related to the leak.

Gaurav Khatik's 52-year-old father Naresh was one of them. Khatik said his father, who suffered lung damage in the disaster, was denied treatment at a hospital built for gas-afflicted patients.

The state-of-the-art Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Centre (BMHRC) -- a busy four-storey 350-bed facility on a sprawling compound on the city's outskirts -- was requisitioned by the Madhya Pradesh state government in March for virus patients.

But the move created "a lot of confusion" and contributed to deadly treatment delays, Khatik told AFP.

A lack of transport due to the lockdown also meant that an average 40-minute journey from the city centre to the hospital became an arduous, longer trip under sweltering conditions.

"People wasted a lot of time going from one hospital to another to seek treatment, which claimed many lives," the 20-year-old said.

The BMHRC turned away people who were not considered virus patients even though they had COVID-19 symptoms, critics said.

They were then denied treatment at other hospitals, with staff saying they did not have the specialised equipment to treat gas-related ailments. They were presumed not to have the virus and no tests were carried out.

"If there was no confusion over the status of Bhopal Memorial Hospital, my father would probably be alive," Khatik said.

Naresh was eventually admitted to a private hospital, where he was finally tested for the virus as his condition deteriorated.

He died within hours of being found positive, leaving his shell-shocked family without a breadwinner and almost $1,180 in medical debt.

"He was our lifeline," Khatik said, fighting to hold back tears.

Activists accuse the government of abandoning the community, whose health conditions make them vulnerable to coronavirus.

"We had alerted the government that if they didn't take proactive action, many gas victims would die from COVID-19 ... but they paid no heed," Rachna Dhingra of the Bhopal Group for Information and Action told AFP.

"They should have reached out to all gas victims suffering from diabetes or hypertension and tested them."

Like Khatik, housewife Gulnaz faced a "nightmare" when her father-in-law Riyazuddin -- who suffered respiratory ailments after the gas disaster -- complained of breathing difficulties.

"We had to struggle a lot... to get help," the 35-year-old told AFP, adding that four hospitals, including BMHRC, refused to take the 65-year-old.

He was finally admitted to the state-run Hamidia Hospital, where he tested positive for coronavirus.

"He was in the hospital only for a day and passed away by evening," Gulnaz, who only gave her first name, said.

Authorities eventually reversed their decision to requisition BMHRC. But the move came too late for many patients, Dhingra said.

The activist said at least five gas victims died from coronavirus because the hospital rejected them.

Bhopal's health commissioner Faiz Ahmed Kidwai told AFP "only one case of a patient turned away is accurate".

"All those who died did not die because BMHRC refused admission," he said.

The 1984 disaster left deep scars across the city of 1.8 million.

Government statistics compiled after 1994 say at least 100,000 people living near the plant suffered ailments including respiratory and kidney problems, and cancer.

Gas-affected mothers gave birth to infants with congenital disorders. Children fell ill from polluted groundwater.

A $470-million settlement inked in 1989 only provided compensation to some 5,000 people, campaigners say.

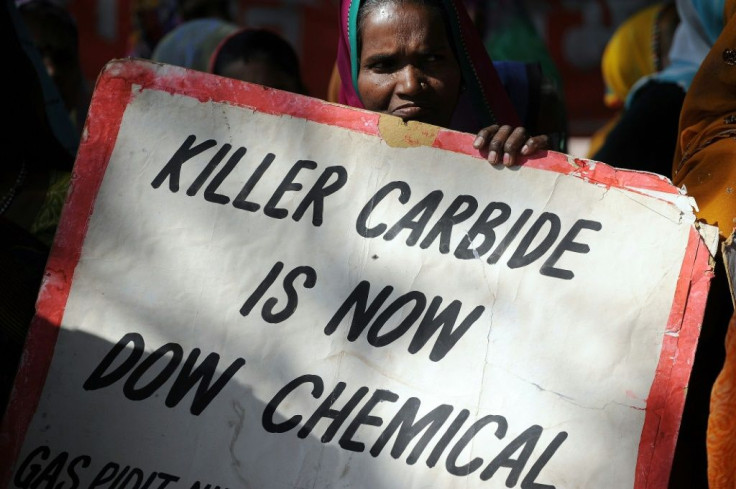

The government in 2012 filed a legal petition seeking further damages from US chemical giant Dow Chemicals, which now owns Union Carbide.

The state's Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief and Rehabilitation department director Ved Prakash told AFP thermal screening was now being carried out on gas victims who have COVID-19 symptoms or are vulnerable "so that they can be isolated and quarantined".

But Dhingra said the move -- which reflects India's push to largely limit testing to people with acute respiratory infections, cough and fever -- would sound a death knell for gas victims.

"They have to test... instead of just screening patients who are high-risk. By the time they turn symptomatic, it will be too late.

"The entire system has collapsed and the most vulnerable are paying with their lives."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.