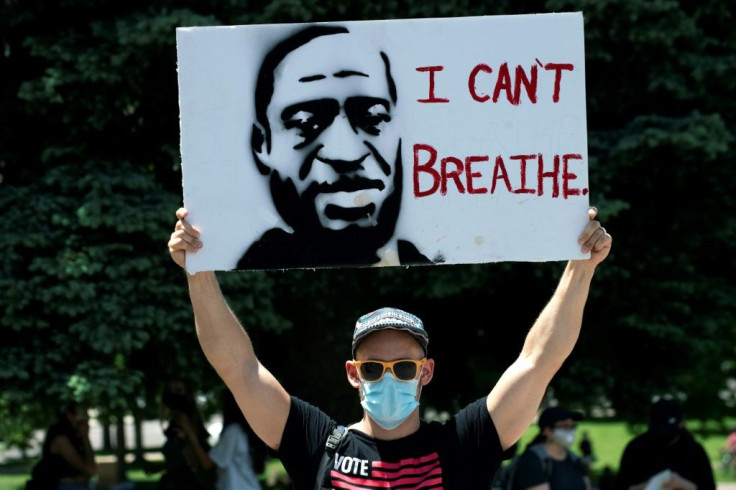

America Divided Two Months After Death Of Floyd

One after another, statues recalling slavery in America keep coming down, and night after night demonstrators taunt police in a groundswell of anger over brutality against people of color.

Two months after African American George Floyd died when a white policeman kneeled on his neck for more than eight minutes, triggering a nationwide and global outcry for justice, the United States is being shaken by an anti-racism surge that, more and more, is dividing its political class.

The days of huge, boisterous nightly marches in cities from New York to Los Angeles may be over but things are still happening. Overnight Thursday, two statues of Christopher Columbus -- for many a symbol of colonization and cruelty to native people -- were taken down in Chicago.

And that same night protesters in Portland, Oregon again clashed with police in a wave of unrest that is now nearly two months old.

With the presidential election 100 days away, this unsettled atmosphere is seen in diametrically opposed ways by the people on either side of it.

For Democrats, taking down Confederate-era statues is a way to acknowledge a racist past and stop glorifying white men who played a part in the oppression of African and Native Americans.

President Donald Trump, appealing to his white, working class base as he seeks re-election with a strong law and order message, calls this practice an act of vandalism and an insult to the heritage of the American South.

As for the protests in Portland, Republicans welcome the administration's sending in federal agents to restore order disrupted by people they label as anarchists.

Critics say these agents in military fatigues use excessive force and are just making the demonstrators more angry and violent.

The death of Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25 was condemned by politicians of all stripes. And as protesters filled the streets every night for weeks, both conservatives and liberals presented ideas for police reform.

But Trump quickly changed the debate to focus on violence committed on the sidelines of the largely peaceful marches.

As calls mounted for defunding the police -- redirecting resources away from them to people trained to deal with problems like substance abuse and domestic violence -- Trump hammered away at Democrats and even his moderate election rival Joe Biden as symbols of a "radical left" bent on simply dismantling police departments altogether.

Trump felt justified in toughening his rhetoric thanks to a rise in gun violence starting in early July in several large cities run by Democrats, and to send in federal agents to Portland and Chicago, even though local elected officials do not want those agents.

His supporters mixed the two problems together -- the wave of protests and the rise in gun violence.

"We had that terrible event in Minneapolis, but then we had this extreme reaction that has demonized police and calls for the defunding of police departments," Attorney General Bill Barr said this week.

"And what we have seen is a significant increase in violent crime in many cities. And this, this rise, is a direct result of the attack on the police forces and the weakening of police forces," he said.

In "50 Days of Democrat Silence on Dangerous 'Defund the Police' Movement," there have been 600 killings in six cities run by Democrats, an association of Republican state attorneys general said Friday.

Thomas Abt, a specialist in urban violence at the Council on Criminal Justice, said the rise in homicides is in fact linked to the coronavirus pandemic because it "has placed the individuals who are the highest risk of violence under great pressure, because the coronavirus is disproportionately affecting the people who are disproportionately affected by violence."

And while there is a tie between the rising gun violence and the unrest over police racism, it is "not for the reason that Trump says," Abt told the progressive news website Mother Jones.

Abt said the death of Floyd triggered a rise in black people's defiance of the police, although in cases of urban violence witnesses and victims of it were less likely to turn to law enforcement.

"In addition, in certain cities we are seeing sudden and arbitrary pullbacks in policing activity," said Abt.

In Atlanta, for instance, many officers called in sick for at least three days after two officers were charged including one who shot a fleeing black suspect in the back, killing him. This was called "blue flu" for the color of the police uniform.

chp/dw/jh

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.