Angry Workers Spurn Ethiopia's 'Industrial Revolution'

Zemen Zerihun thought he'd left farming behind and found the ticket to a better life when he began a job cutting fabric for a clothing company at a massive industrial park in southern Ethiopia.

But the 22-year-old ended up quitting within months, weary of working eight hours a day, six days a week and still not making ends meet earning $35 a month.

Managers were so strict they would go into bathrooms and yank out workers deemed to be taking too long, he said.

His supervisor would loudly berate him as "slow" and "lazy" when he failed to keep pace on the production line, he told AFP.

"After I joined the company, I suffered," he said. "The supervisors treat you like animals."

Experiences like his highlight a major challenge facing Ethiopia's push to embrace industrialisation and become less dependant on agriculture.

By attracting foreign investors through cheap labour, it wants to follow the model of China and other Asian nations in creating a robust manufacturing sector that can offer badly needed jobs for its young workforce.

But despite high unemployment, young Ethiopians are not going along with it, preferring to quit rather than stay in jobs where they feel underpaid and disrespected.

Thousands of employees have already walked out of the country's new and burgeoning network of industrial parks.

At the Hawassa Industrial Park, where Zemen worked, staff turnover in 2017-18 "hovered around 100 percent," according to a May 2019 report from the Stern Center for Business and Human Rights at New York University.

The added recruitment and training costs are a main reason why, in the eyes of manufacturers, Ethiopian labour has "turned out to be considerably more costly than the government had initially advertised," the report said.

Government officials say they are taking steps to address workers' concerns while balancing them with industry representatives' interests.

But labour organisers argue the measures are too little, too late, leaving them no choice but to begin unionising the parks -- a development Zemen says is long overdue.

"The government needs to pay attention to what is happening in the industrial parks," he said.

"They think they are giving everyone good jobs, but some of the workers, they are really struggling."

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed sees industrial parks as an important engine of growth that can help stave off unrest ahead of elections tentatively planned for August.

Yet the strategy was adopted several years before Abiy came to power, after the government realised in 2014 that agriculture couldn't provide enough jobs for a booming population, said Arkebe Oqubay, an architect of the strategy and now special adviser to the premier.

Ethiopia is one of Africa's fastest-growing economies but youth unemployment remains a major problem.

The World Bank estimates that two million people enter the workforce every year.

Despite long-running efforts to restructure the economy, officials estimate that manufacturing still only makes up 10 percent of economic activity.

As they work to ramp up the sector, officials say they have learned the lessons of places like Bangladesh -- where at least 1,134 people were killed in the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013 -- and are committed to avoiding unsafe and unsustainable working conditions.

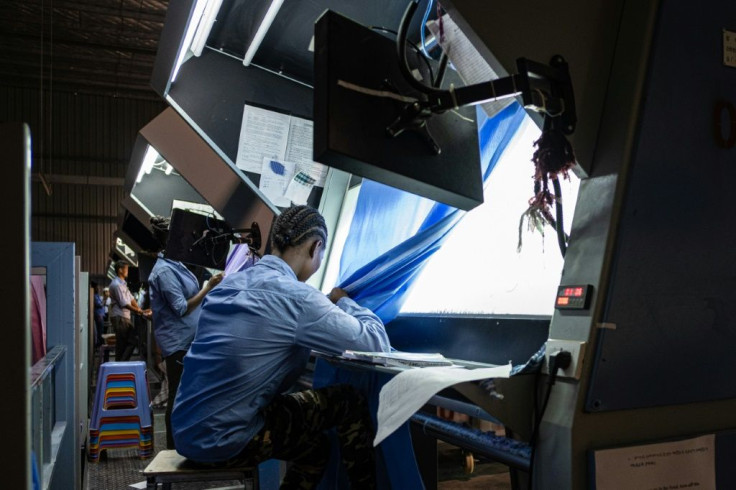

The flagship Hawassa park, a campus of 52 factory sheds occupied by American, European and Asian companies producing garments and textiles, opened in 2017.

Its roughly 30,000 workers sew fabric into T-shirts, sportswear or other sought-after items.

By year's end, some 30 industrial parks will be operating across Ethiopia, specialising in sectors like machinery production and information and communications technology, Arkebe said.

Currently 12 parks have been built.

The parks have already yielded dividends, Arkebe said, raising foreign direct investment to $4.3 billion in 2017 -- a fourfold increase over five years earlier.

But wage levels are under the spotlight.

The $26 monthly base pay at Hawassa makes Ethiopian garment workers the lowest paid in the world, the NYU Stern Center report said.

Though the amount is not uncommon for entry-level employees in a country with no minimum wage, workers say it barely covers food, transport and rent.

Even those leasing cramped apartments with three or four co-workers and sleeping in shifts on shared mattresses say they don't make a decent living.

Eight months after resigning, Zemen is living with his family and still looking for a new job, but he has no regrets.

He'd rather grow food for himself on the family farm than toil at the factory which he'd initially seen as his escape, he said.

He is far from the only worker to have quickly grown disillusioned when the reality of factory life failed to match his expectations.

Tony Kao, deputy general manager of JP Textile, said Hawassa workers faced challenges switching from agricultural to industrial work.

"It took some time for them just to learn industrial work. They now have to be on time to work and now they have to learn new skills, they have to learn how to operate the machines which is a whole new chapter for them," he said.

Medihant Fehene left her Hawassa factory job, too.

"I'd have to wake up to catch the bus at 5:30 to start work at 6:00, or if I took the afternoon shift I would not get home until 11:30, when it's dark and not safe for a woman to be outside," she said.

Among measures the government is exploring to address such frustrations is giving companies land for dormitories for workers to rent at subsidised rates, Arkebe said.

However, he also defended low wages, saying they help ensure firms invest in Ethiopia rather than countries where manufacturing is more established.

"If wages are high and investment doesn't come, new employment is not going to be created," Arkebe said.

"The livelihood of workers can improve when their productivity improves," Arkebe added, comparing the process to the "industrial revolution" in Britain and the United States.

Such statements play well with industry representatives.

"Ethiopia is the garment future. Everybody's looking at Ethiopia now," said Raghavendra Pattar, head of Nasa Garment Plc in Hawassa.

Ethiopian workers have had the right to organise since the 1960s, but Pattar said he saw no need for unions to be established at the industrial park.

But Ayalew Ahmed, vice president of the Confederation of Ethiopian Trade Unions, told AFP that the first "task forces" to begin organising workers would form early this year.

"If the employers volunteer to have trade unions in the company, that will be OK. Otherwise we will establish them outside the company," he said.

The government backs workers' right to organise, provided it is not too disruptive, Eyob Tekalign Tolina, a state minister of finance and one of Abiy's top economic advisers, said.

Factory owners at Hawassa meanwhile seem to face no shortage of potential replacements for those who quit.

Inside the park, 22-year-old Tekle Baraso Bonsa took a break from dyeing yarn to explain how he was using his $33 a month wage to put himself through university.

"If I weren't doing this," he said, "I'd be shining shoes."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.