Animal Matchmaking: Scientists Try To Revive Extinct Galápagos Tortoises

Scientists are trying to bring an extinct species back to life, and they’re going to do it by setting up love connections between tortoises.

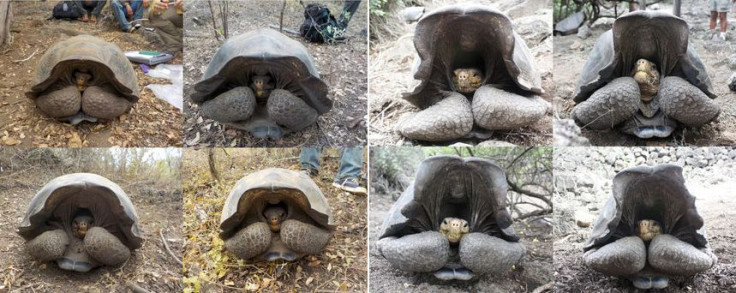

Humans drove it to extinction about 150 years ago but the Floreana Island tortoise is getting a second chance after scientists found reptiles with genes from the lost species living around a volcano on a neighboring island. The team hopes to use these mixed-ancestry giant tortoises, which they brought into captivity from Wolf Volcano on northern Isabela Island — the highest peak on the largest of Ecuador’s Galápagos Islands — to recreate and revive the Floreana tortoise.

One of the researchers on the project, Yale University’s Joshua Miller, told International Business Times the plan is to put the tortoises, which are hybrids of the Floreana tortoise and other existing species, into corrals with one another and encourage them to mate. He referred to it as “matchmaking” because the tortoises are paired up such that their offspring would move the group toward a more purer version of the Floreana, whose scientific name is Chelonoidis elephantopus.

“We can’t force individuals to mate with each other,” he said. “They are autonomous animals.”

Through the breeding, the scientists will “try and encourage an increase of the Floreana ancestry over time,” according to Miller.

Over time is right: Miller said it takes about 20 years for a tortoise to reach reproductive age, which means new generations might come slowly. And it would take several generations to produce a pure Floreana tortoise, marked by its shell’s saddleback shape, compared to the dome-shaped shells of the other species on Isabela.

But he emphasized this purebred tortoise is not the immediate goal; rather his team is aiming to whip up baby tortoises quickly and release them into the wild when they are big enough, repopulating Floreana Island.

It’s possible that once they are in the wild and on their own, the more genetically pure Floreana tortoises will further the scientific agenda.

“Evolution by natural selection is what made these tortoises different in the first place,” Miller said about the extinct Floreana species.

While mating in the specific conditions of Floreana Island, “natural selection may proceed as it did in the past” and move the hybrid tortoises closer to the features of their lost brethren.

While human interference is what wiped out the Floreana tortoise to begin with, it is also what has made this de-extinction project possible.

“Ironically, it was the haphazard translocations by mariners killing tortoises for food centuries ago that created the unique opportunity to revive this ‘lost’ species today,” according to a study in the journal Scientific Reports written by Miller and the rest of the team.

According to their report, native species have gone extinct in the Galápagos mostly because humans have introduced non-native species since discovering the islands in the 16th century and tortoises were “killed mostly for food and oil by whalers, sealers, buccaneers, and early colonists.”

The Floreana tortoise was one victim of the invasion, but it appears mariners translocated them before their extinction to Isabela Island, where they lived among and bred with other tortoises — paving the way for scientists to find the Floreana hybrids today.

“Ancestors of these tortoises were probably thrown overboard by mariners who did not have space for them on ship, and then over generations they mated with native species,” Yale University explained in a statement.

“Tortoises with Floreana ancestry are living ‘genomic archives’ that retain the evolutionary legacy of the extinct species, removing the need for the cloning methods that have been proposed to bring back extinct species,” the study says. “The Floreana tortoise breeding program is anticipated to generate thousands of offspring over the next few decades. When repatriated to Floreana Island, these tortoises can once again play their critical role as ecosystem engineers.”

According to a statement from Flinders University on the captive breeding project, which is an international effort, the scientists may be able to release a batch of young tortoises on Floreana Island within five years.

If everything works out, the team may be able to replicate their project with the extinct C. abingdoni from Pinta Island, which went extinct in 2012 after their last member, dubbed Lonesome George, died.

While the scientists were searching for tortoises on Isabela Island with Floreana ancestry, a similar search for Pinta tortoises did not turn up anything. But Miller told IBT that he thinks there are hybrid Pinta tortoises there, waiting to be found.

“If we get funding, we will go back and look for tortoises from Pinta lineage as well,” senior study author Adalgisa “Gisella” Caccone said in the Yale statement.

For now, the researchers are focusing on the slow restoration of the Floreana tortoise.

“Of course, it is easier and faster to destroy than to restore,” she said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.