Animal-Like Robot Instinctively Adapts And Recovers When Injured

Imagine a robot that, when damaged, gets up, shrugs off and keeps plodding on like nothing happened. Reacting like this to a situation that is unpredictable and hostile is something robots are not quite good at, as it requires a level of adaptation that, as of now, only biological organisms possess.

In a new study, detailed in the journal Nature, scientists described the use of an “intelligent trial and error” algorithm that allows robots -- in this case, a six-legged machine and a robotic arm -- to adapt and move beyond their pre-programmed contingency plans.

“Current damage recovery in deployed robots typically involves two phases: self-diagnosis, followed by selection of the best pre-designed contingency plan,” the team of French researchers wrote, in the paper. “Such self-diagnosing robots are expensive, because self-monitoring sensors are expensive, and are difficult to design, because robot engineers cannot foresee every possible situation.”

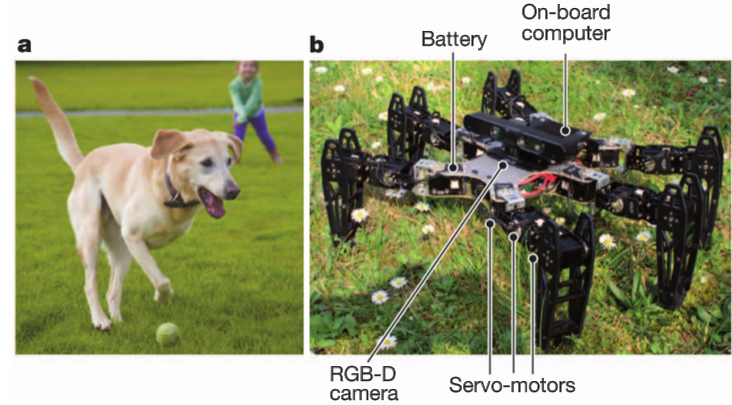

Contrast this to how an animal, a dog, for instance, responds to an injury to one of its legs. The dog would learn -- through a process of trial and error -- a way to move that makes the best use of its uninjured legs and also minimizes pain to the injured one. With this kind of adaptation in mind, the researchers built upon an earlier work on a self-diagnosing six-legged robot, incorporating an algorithm that allowed it to recover from damage, and to do so in a span of seconds.

“Time is of the essence,” evolutionary roboticist Josh Bongard at the University of Vermont in Burlington, who built a self-diagnosing robot in 2006, but is not part of the current research, reportedly said. “If a car starts to skid off the road, it needs to find a way to recover very quickly.”

To help their hexapod recover faster than previous machines, the researchers equipped it with a library of nearly 13,000 walking patterns calculated in advance using a computer model of the robot. This repository was likened to an animal’s instinct by the researchers. Armed with this knowledge, the robot found the most efficient way to move around -- in under a minute. The algorithm was also successfully tested on a damaged robotic arm.

And, if news of a six-legged, self-repairing robot brings images of menacing Terminator-like machines to mind, such fears might be slightly overblown, according to Jean-Baptiste Mouret, an artificial-intelligence researcher at France's national computer science agency Inria.

“Almost all animals are built to adapt to a small injury,” he reportedly said. “That doesn’t mean they want to take over the world.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.