Animals’ Ability To Remember Past Events Could Prove Critical For Alzheimer's Treatment

The ability to remember a sequence of events as they happened seems like a quality restricted to humans. Previously, we had no clue if animals could do something similar, which is not the case anymore. A group of scientists discovered rats can also remember episodes of past memory.

The find, a first in the field of neuroscience, is not exactly similar to human’s ability to remember things but could be the key to develop better treatments for Alzheimer's disease.

"The reason we're interested in animal memory isn't only to understand animals, but rather to develop new models of memory that match up with the types of memory impaired in human diseases such as Alzheimer's disease,” lead author Jonathon Crystal said in a statement.

Alzheimer's disease destroys memory and other mental functions with time. There are some treatments to alleviate the effects of the condition, but no drug has been able to cure it. Scientists have been conducting preclinical studies to advance existing treatments, but so far, nothing has worked as one would expect.

The reason for this could be targeting the wrong type of memory. According to Crystal, most researchers involved preclinical studies examine newly-developed drug samples on spatial memory — a type of memory which can be accessed easily in animals.

They used results of those tests to determine whether or not to go ahead with that particular compound. But here is the catch, spatial memory is not the memory that relates to some of the most harmful effects of Alzheimer's disease. It is "episodic memory" or the ability of a person to remember past events and that too in the same order of their occurrence. If the sequences of these events is changed, the whole episode would not make any sense.

“If your grandmother is suffering from Alzheimer's, one of the most heartbreaking aspects of the disease is that she can't remember what you told her about what's happening in your life the last time you saw her," Danielle Panoz-Brown, first author of the study, said in the statement. "We're interested in episodic memory — and episodic memory replay — because it declines in Alzheimer's disease, and in aging in general."

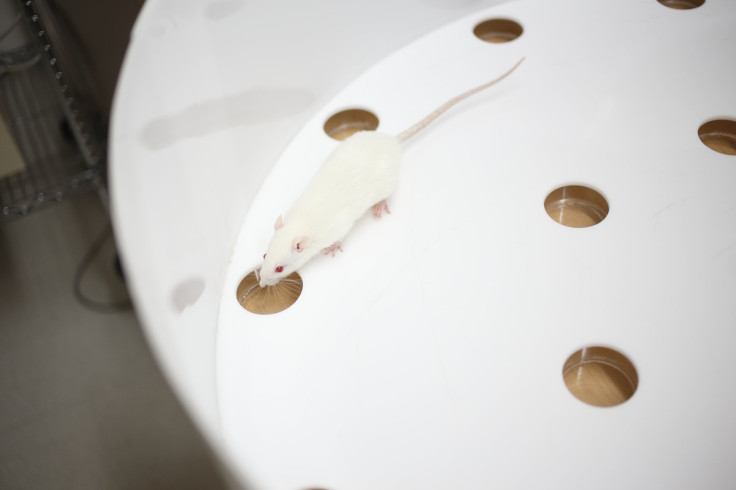

That said, in order to gain access to episodic memory in rats, Crystal and colleagues trained 13 rats to memorize a list of 12 different odors. Then, they placed the animals in an "arena" of odors to see if they could identify second-to-last and fourth-to-last odor on the list. The group rewarded the rats whenever they correctly identified the odor and even changed the number of scents in the test list to make sure the animals are actually remembering the position of the odor on the original list and not just the scent.

The observations of the study confirmed the animals recalled the whole list, as they learned, and correctly identified the odors in 87 percent of the cases. Among other signs of episodic memory, the group noted the rats had long-lasting memory, with more resistance to interference from other memories. They also suppressed the activity of hippocampus, the site in brain relating to episodic memory, to confirm the animals were actually using it to complete the tasks assigned to them.

Noting the results of the latest work, Crystal stressed on the need of new ways to test episodic memory replay in rats. He added rats with conditions similar to Alzheimer’s are being created with genetic modifications.

"We're really trying to push the boundaries of animal models of memory to something that's increasingly similar to how these memories work in people," the researcher concluded. "If we want to eliminate Alzheimer's disease, we really need to make sure we're trying to protect the right type of memory."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.