Astronomers Discover ‘Infant’ Exoplanets That May Help Unlock Mysteries Of Planetary Birth And Evolution

Over the years, astronomers have discovered and confirmed the existence of nearly 3,000 exoplanets, but there is one question that they still haven’t been able to answer satisfactorily — how exactly do planets form?

That is why, the discovery of two “infant” planets that are still in their early formative years — one of the handful of newborn planets found to date — is bound to cause excitement. The two giant planets, both just a few million years old — compared to our 4.5 billion-year-old solar system — are among the youngest ever discovered.

“These two papers are probably the first solid evidence that you can find planets close to their stars at such a young age,” Trevor David from the California Institute of Technology, who is the lead author of one of the studies published in the journal Nature, told the Guardian.

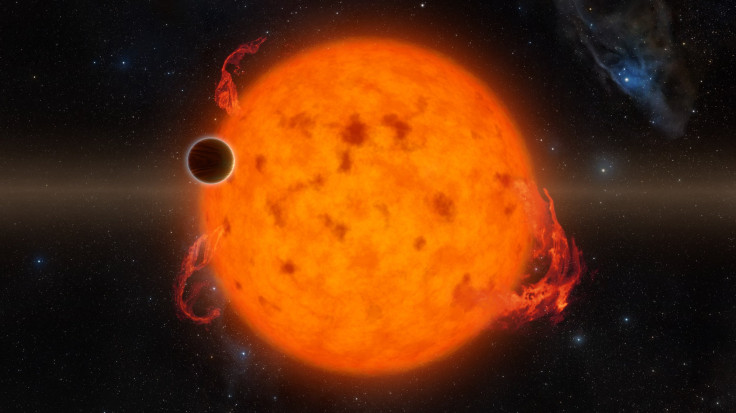

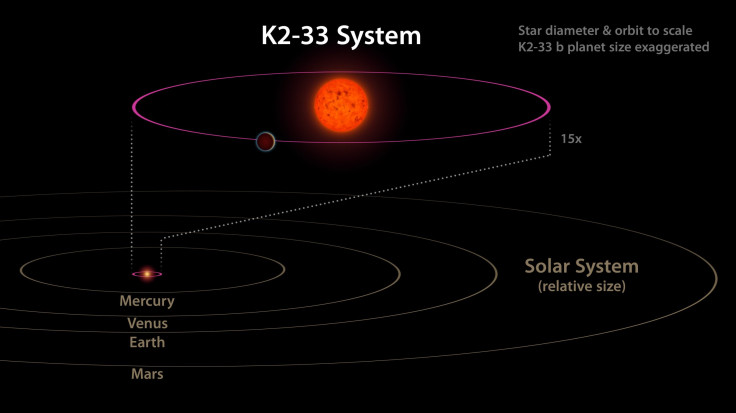

One of the planets, K2-33b, is slightly larger than Neptune, lies 470 light-years from Earth and is estimated to be between 5 million and 10 million years old. The other planet — a “hot Jupiter” orbiting the star V830 Tau located roughly 430 light-years away, is the younger of the two at just 2 million years old.

Both the planets are located extremely close to their parent stars, completing an orbit in just five days.

“Planet formation is a complex and tumultuous process that remains shrouded in mystery,” NASA said in a statement released Monday. “For astronomers, attempting to understand the life cycles of planetary systems using existing examples is like trying to learn how people grow from babies to children to teenagers, by only studying adults.”

In addition to providing invaluable empirical data about how planets form and evolve, the discoveries would also help scientists answer another key question — how do such massive objects wind up so close to their parent stars?

“After the first discoveries of massive exoplanets on close orbits about 20 years ago, it was immediately suggested that they could absolutely not have formed there, but in the past several years, some momentum has grown for in situ formation theories, so the idea is not as wild as it once seemed,” David said in the statement. “The question we are answering is: Did those planets take a long time to get into those hot orbits, or could they have been there from a very early stage? We are saying, at least in this one case [K2-33b], that they can indeed be there at a very early stage.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.