As Baghdad Government Stumbles, Iraqi Kurdistan Officials Call For Partition

Kirkuk Gov. Najmaldin Karim swept to office on the promise of oil-fueled prosperity for residents of the Kurdish-majority province in northern Iraq. But, with oil exports at a record low, it's a pledge that the former Washington-based neurosurgeon has failed to keep.

In May, shipments of crude from fields in the Kurdistan region fell to 430,000 barrels per day from 512,000 barrels daily the previous month. Government workers, hired on dreams of a booming economy, have gone unpaid for four months and scores of unemployed men scour the city's streets for work, however temporary.

In a desperate bid to turn things around, Karim has proposed a radical fix: breaking away from the central government in Baghdad.

"Kirkuk needs to get away from Baghdad," he recently told reporters, adding that the chaos in central government — embroiled in a dispute over the appointment of a new cabinet — is responsible for impoverishing the oil-rich province.

Oil is the main source of Iraqi Kurdistan’s revenues and the suspension of exports over the last several months has further limited the already cash-strapped region. If Karim's call for separation is realized the region could take control of its oil exports and ensure that money flows back into the local economy.

But analysts are skeptical that disorder in the Iraqi capital is behind Karim's pronouncement. "I don’t agree that the reason to [break away] is the chaos in Baghdad," Mike Knights, an Iraqi expert from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told International Business Times. "The reason to do it is that they are [an independent] people and they have the right [to self-govern]."

However, complete autonomy remains a pipe dream, Daniel Serwer, an expert on Iraq from the Middle East Institute, told IBT. "The problem with this idea is that geopolitics are against it. Neither Turkey nor Iran, the Kurdistan Regional Government's nearest neighbors, will accept its sovereignty. Baghdad won't either, and in addition will dispute its borders, perhaps by force at some point," he said.

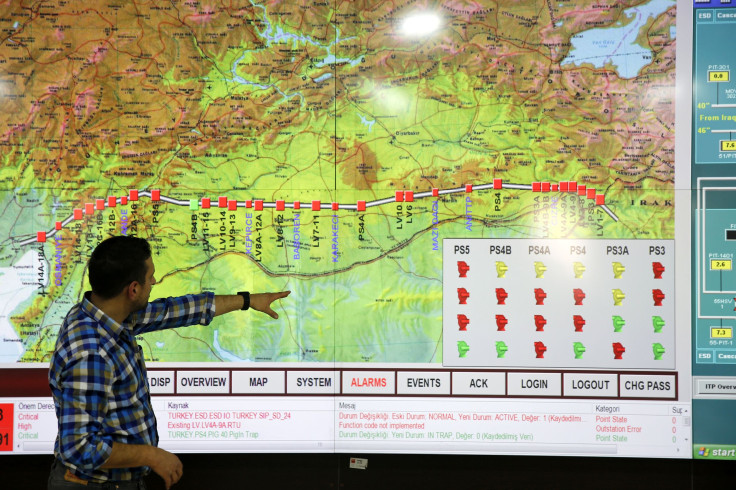

Kirkuk's faltering economy is likely to decline further, experts say. Attacks on the oil infrastructure from Islamic State militants combined with Baghdad's decision to suspend exports through the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline in March has wreaked untold damage on the province.

Consequently, Knights said Karim may feel compelled to force the workers at Kirkuk's oil wells to open the valves and start exporting to Turkey once more. Kurdish military and police forces are on standby on the understanding that they could soon receive orders from local officials to enter the region's oil fields.

But Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, has yet to back Karim's endeavor, preferring to concentrate on securing its share of an estimated $15 billion worth of financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund.

This does not leave Karim with many choices. "[Karim can either] wait it out and see if the KRG and Baghdad cooperate to let Kirkuk export through the pipeline, or call on the Peshmerga [Kurdish forces] that are sitting 50 meters away and have them go and tell the guys working there to make it happen," Knights said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.