'Becoming Cousteau' Plumbs Depths Of French Ocean Explorer

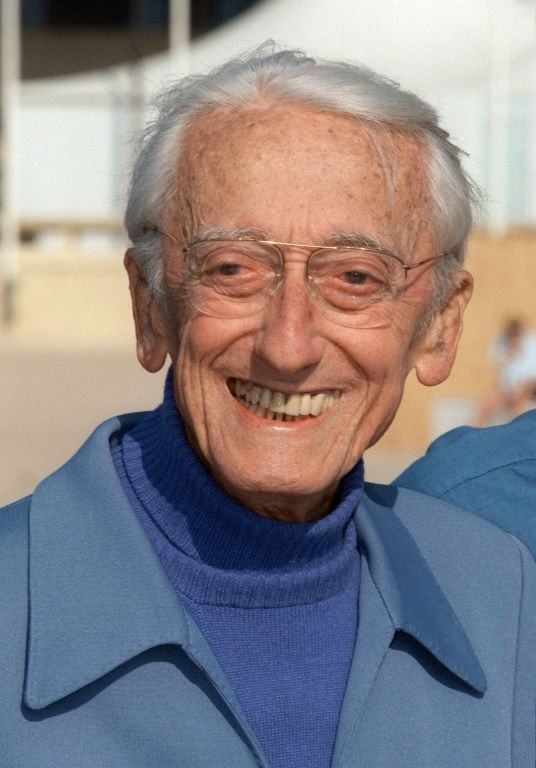

Explorer, inventor, filmmaker, environmentalist and once even an oil prospector: the complicated journey of Jacques Cousteau is laid bare in a new film about one of the world's most famous Frenchmen.

"Becoming Cousteau," which hits theaters in the United States this Friday, traces the extraordinary life of the man through archive footage and interviews, and was compiled by double-Oscar nominee Liz Garbus.

"I grew up on Cousteau, and I grew up watching his shows... And my feeling was as I revisited this childhood hero of mine, that there were aspects in his life that I certainly did not know," Garbus told AFP in Los Angeles.

Garbus trawled through hundreds of hours of footage -- much of it never released publicly -- to capture a flavor of a life lived underwater.

"Cousteau was a filmmaker and because his imagery was so groundbreaking, I wanted our viewer today to be immersed in that imagery," she said.

Born in 1910, Cousteau had never set out to be a diver. His initial focus was on the skies.

But at the age of 26, just after begining his training as a pilot at France's naval academy, a serious car accident left him unable to fly.

During his convalescence, he was advised to take up spearfishing. It was a piece of advice that would change his view on life forever.

"As soon as I put my head under water, I understood; I had a shock: an immense and completely virgin domain to explore," he said.

That exploration required ever more complicated kit -- kit that did not exist. So Cousteau invented it.

Inspired by Leonardo da Vinci's "slightly crazy" sketches, he borrowed a regulator designed for car engines and, with engineer Emile Gagnan, produced the self-contained diving suit that forms the basis of those still in use today.

"I didn't want pipes, I wanted to be completely independent", he says.

After World War II, he mounted the first expedition aboard the "Calypso", a converted minesweeper that set sail for the Red Sea in 1951.

And wherever he went, so did his cameras, thanks to his diving suit and the waterproof camera housings that he had developed.

The footage he brought back was the first glimpse that many people had of the vast underwater world.

While the modern day conception of Cousteau is of a crusading environmentalist, that was a period of his life that came later.

Like countless contemporaries in the post-war years, Cousteau did not show any real ecological awareness, using explosives to bring fish to the surface.

In order to finance the "Calypso", he even started prospecting for oil, discovering reserves in Abu Dhabi in the process.

"I think I was naive... but I didn't have a penny!", he would later plead after his conversion to environmental protection.

In the 1950s, Cousteau produced "The Silent World", which won the Palme d'Or at Cannes in 1956 and an Oscar for best documentary the following year.

He was furious to see his films classed as "documentaries", insisting that they were "real adventure films", says Garbus.

The following decade, he abandoned the cinema to go into television with a series of documentaries on underwater life, the first of their kind.

He was never entirely at peace with the medium, but recognised it had its benefits -- particularly as his consciousness grew about the need to preserve the natural environment.

"Though it is an aesthetic sacrifice, it is a way to reach millions of people rapidly," he said.

These "films are no more about beautiful little fish but are dealing with the future of mankind."

As a pioneer in the field of ecology, Cousteau was sounding the alarm about "the sea in distress" to the US Congress in 1971.

By the end of the 1980s, he was telling anyone who would listen of the dangers of global warming --long before the mainstream woke up to the damage humanity was doing to the planet.

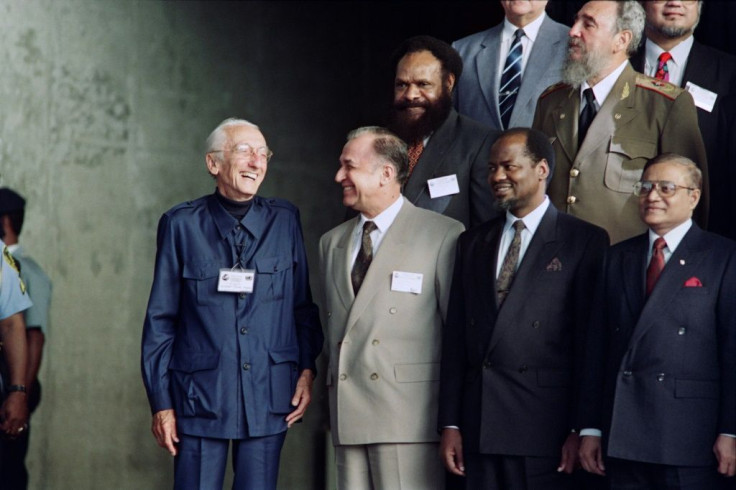

His influence was such that at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, Cousteau was the only non-world leader in the official photo.

"What Cousteau was able to do because of all the love he had built up over the decades, to translate that love and respect into something that was a crucial message... There's nobody who has that power today," says Garbus.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.