In Bergamo, Memory Of Coffin-filled Trucks Still Haunts

Images of army trucks transporting piled-up coffins out of the Italian town of Bergamo provided a shocking testament to the horrors of coronavirus and one year on, the memories are still raw.

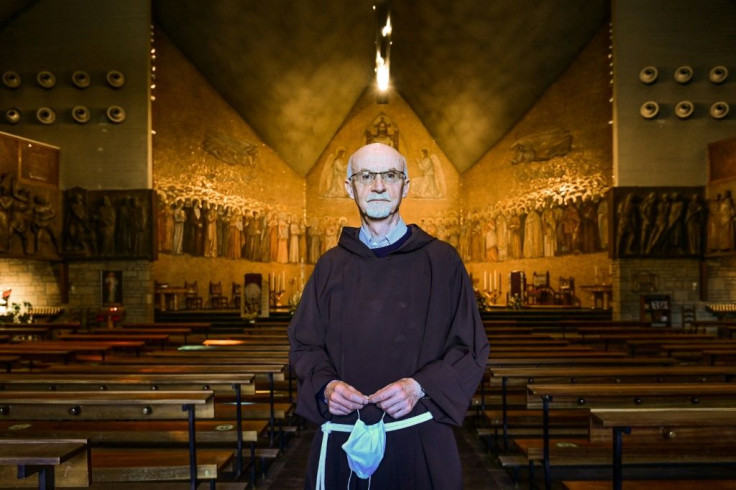

At the height of the pandemic last year, Father Marco Bergamelli was blessing coffins every 10 minutes in the northern Italian city.

"This place was full of coffins, there were 132 lined up at the foot of the altar," he said, opening the doors of the church at the Monumentale cemetery to AFP.

"At the beginning, the trucks came at night, nobody was supposed to know the coffins were being taken elsewhere."

The camouflaged vehicles took away up to 70 coffins a day from the church, where they were collected after the local mortuaries filled up.

The coffins were transported to cemeteries in other northern cities such as Bologna and Ferrara.

Many of the bodies that remained in Bergamo were buried in haste, often without headstones but with signs bearing photos and names of the deceased.

Almost everyone in the town lost a member of their family, a friend, colleague, or neighbour.

In March 2020 alone, 670 people died in the city of 120,000 inhabitants and almost 6,000 in the province of the same name -- five or six times the normal toll for that time of year.

"People saw their loved ones leave in an ambulance with a fever, and they were returned as ashes in an urn, without ever being able to say goodbye," said the 66-year-old Bergamelli.

"It was like wartime."

Prime Minister Mario Draghi visited Bergamo Thursday to mark a national day of remembrance for the victims of the coronavirus pandemic, which has killed 103,000 people in Italy, according to official statistics.

"This place is a symbol of the pain of an entire nation," Draghi said after laying a wreath of flowers at the cemetery and joining a minute of silence for the dead.

But a grim sense of deja vu pervades the area, as the city is once again locked down along with most of the country amid a fresh wave of infections.

At the Seriate hospital east of the city, the intensive care unit is once again at capacity, its eight beds occupied by coronavirus patients, even if numbers are lower than last year.

"Covid is more aggressive now, with many cases of the new English variant," said Roberto Keim, the unit's director.

There are many here who criticise authorities for acting too slowly to recognise the scale of the crisis last year and not imposing swift restrictions to stem the virus' spread, including banning gatherings.

"At the beginning of March, we saw people going to funerals for victims of Covid, and themselves dying a few weeks later," said Roberta Caprini of the Generli Funeral Home.

The 38-year-old was left to manage unprecedented demand for the family business after her father and uncle both contracted coronavirus. They later recovered.

"Normally, we organise about 1,400 burials a year. But in March 2020, we did 1,000," she said.

To allow relatives in quarantine to say their final goodbyes, Caprini had the hearse pass underneath their balconies, and took photos of the dead herself.

But proper mourning was impossible for many.

"We spent a month not knowing where my father's body was," said Luca Fusco, recalling the 85-year-old's death in a care home on March 11, 2020.

Fusco's son Stefano created a Facebook group demanding justice for the dead, which now has 70,000 members.

The group "Noi Denunceremo" (We Will Denounce), led by Luca Fusco, has already filed more than 250 complaints with prosecutors over the way authorities handled the Covid crisis. A judicial inquiry is under way.

It took two weeks after the first cases appeared in the province on February 23 last year for the authorities to lock down the entire Lombardy region, a measure extended one day later to the whole of Italy.

Fusco claims nobody wanted to shut down a region that is the engine of Italy's economy.

"The people of Bergamo felt abandoned. In acting sooner, the authorities could have saved thousands of lives," he said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.