The Berlin Wall, 1961-1989: A Timeline Of A Divided Germany

The Berlin Wall went from the impenetrable symbol of a monolithic East to nothing more than a concrete wall in less than a few hours on Nov. 9, 1989, but what put into motion the fall of the Wall and the German Democratic Republic, better known as East Germany, started long before. Before the construction of the Wall in 1961, East Germany had a serious “brain drain” problem. East Germans, particularly the young and educated, were fleeing the totalitarian communist regime and weak East German economy for opportunities in the West. The rest of the East-West German border was closed in 1952, but the division of East and West Berlin was largely an imaginary line guarded on each side. People simply ran across.

Aug. 12, 1961: To stop brain drain, East German State Council Chairman Walter Ulbricht signed orders to close the border with West Germany and build up fortifications in Berlin. Within a few days, guards had laid down barbed wire and destroyed roads to stop vehicles from crossing. In the next few years, the border would become increasingly militarized and fortified.

Aug. 22 and Aug. 24, 1961: Ida Siekmann, 58, lived on the Bernauer Strasse, a road that ran along the border of East and West Berlin. Many of the people living in her apartment building had jumped out of their windows into West Berlin to escape the East. Ten days after Ulbricht signed the order to build the Wall, Siekmann jumped out of her fourth story window into West Berlin territory, but firefighters were unable to deploy a life net in time to catch her. She died later that day, becoming the first fatality among those trying to cross into West Berlin.

Two days later, Günter Litfin, 24, became the first person shot trying to do so. His plans to move to West Berlin were nixed when the border was closed, so on Aug. 24 he attempted to swim across a narrow canal that linked two rivers in the city. It was the same day that East German border guards were given the order to shoot any would-be escapees. Guards discovered him swimming across the canal and killed him.

May 5, 1963: Machinist Heinz Meixner, a young Austrian who had fallen in love with an East German girl while deployed to the East for work, succeeded with one of the most creative escapes from East to West Berlin. He was sneaking out his girlfriend and her mother. Instead of digging a tunnel or running across with them, he rented a small convertible, cut out the windshield and took out just enough air from the tires so the car would slip under the gate at Checkpoint Charlie. When he pulled up to the gate and gave the East German guards his papers, he simply ducked and drove the convertible right underneath and to the West. Most people weren’t as creative; the majority of escapees got across the border by bribing officials or escaping through third countries.

June 26, 1963: U.S. President John F. Kennedy delivered his famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech at the steps of the Rathaus Schoeneberg where the West Berlin Senate met. The speech was a show of solidarity with West Germany and the Berliners who had only lived in a divided Berlin for two years.

1965: East Germany began building the “third generation” fortifications, which included a larger concrete barrier that would become what would be referred to most commonly when people mentioned the Berlin Wall -- even though the fortifications included far more than just a wall.

1975: East Germany began building the “fourth generation” fortifications, called the Grenzmauer 75, or Border Wall 75. It included an improved, 11-foot, 10-inch concrete wall with steel tubing across the top to make it harder to climb. This is the final and most sophisticated iteration of the wall. It had an enhanced “death strip" of fortifications along the East German side of the new and improved interlocking concrete slab barrier closest to West Berlin. Starting on the East German side, there was a fence specifically made to be difficult to scale, a signal fence that would trip an alarm, anti-vehicle fortifications like “Czech hedgehogs,” watchtowers, spotlights, strips of 5-inch spikes, minefields (until 1983) and trenches before the actual wall. Trying to cross was a death wish.

Here’s what it looked like along the Bernauer Strasse, where Ida Siekman lived 14 years earlier:

Jan. 22, 1985: The East German government demolished the Church of Reconciliation, a Berlin landmark along the Bernauer Strasse completed in 1894. The church stood along the East-West border, and East Germany actually encapsulated the church in the death strip, blocking it off from both East and West Berliners. Would-be escapees often would use the church for cover while trying to get closer to the fence because it blocked the view of border guards. A new Church of Reconciliation was built at the site in 2000 and is open to the public.

June 12, 1987: U.S. President Ronald Reagan delivered his famous “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” speech at the Brandenburg Gate. It’s become Reagan’s most famous speech, but it wasn’t at the time. The general consensus amongst historians is that it didn’t influence Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s opinion of the wall. Gorbachev had already taken steps to open up the Eastern Bloc as leader of the USSR beginning in 1985. In 1990, Reagan would take a ceremonial swing at the Wall with a sledgehammer.

May 1989: Communist Hungary began tearing down its own border fence with Austria. A couple of months later, the respective Austrian and Hungarian foreign ministers held a very public “fence-cutting” photo op, in which they sliced through the border fence with bolt cutters. More than 10,000 East Germans eventually fled to Austria from Hungary, and East Germany knew it had to do something about it. A botched announcement of a suspension of visa requirements by an East German official would ultimately be what spurred the fall of the wall six months later.

September-October 1989: The “Monday demonstrations” began Sept. 4 in Leipzig, East Germany. They were a series of peaceful protests against the East German communist government that grew out of a series of prayer and discussion sessions with the Revs. Chistian Fuehrer and Cristoph Wonneberger. Each Monday night a crowd would gather at Nikolaikirche, or St. Nicholas Church, and by early October the number grew to more than 70,000 people. Protesters prepared for a violent crackdown by the East German police and the army, but it never came.

Oct. 18, 1989: Longtime East German leader Erich Honecker was forced out of office by reformists within the East German government. Honecker had led East Germany since 1971 and believed in the wall. His protege, Egon Krenz, took over and promised there would be some reforms, but his promises failed to satisfy the hundreds of thousands of East Germans set on true change.

Oct. 23, 1989: The Monday demonstration crowd in Leipzig grew to an unprecedented 320,000 people, out of a city population of a half million. East German authorities couldn’t ignore it anymore.

Nov. 4, 1989: The following Saturday after the massive demonstrations in Leipzig, East Berliners held their own protest, which would come to be known as the Alexanderplatz demonstration. Some 500,000 to 1 million Berliners came out to demand reform. East German authorities tried to subvert the protests, but there was little to no violence. Artists, opposition party members and even some representatives of the Communist regime came out to speak at the demonstration.

Nov. 9, 1989: Around 7 p.m., at the end of an otherwise bland press conference, East German spokesman Günter Schabowski read off a note on a change in policy to a group of sleepy reporters on live television. The note read East Germany would allow citizens to travel to West Germany through any border crossing with little more than a passport in the coming week, but Shabowski’s interpretation was that it would go into effect immediately.

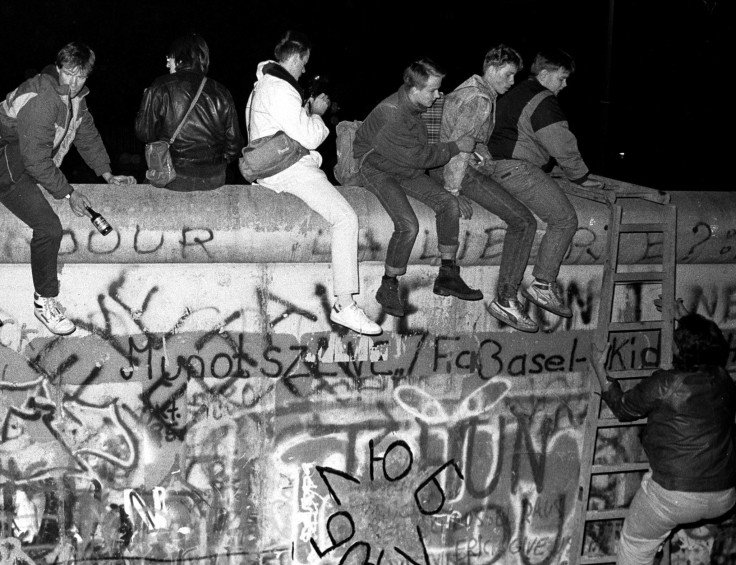

East Germans watching the press conference were at first confused, but excitement about the possibility of breaking the 28-year divide in Berlin drove them into the streets and their nearest border points. Within a few hours, thousands had gathered at Berlin Wall checkpoints and were demanding to be let through per the order Schabowski had read.

Later that night, a commander in charge of the Bornholmer Strasse crossing knew he didn’t stand a chance of keeping the crowd away without injuries. At first Lt. Col. Harald Jager started letting the more vocal people through with warnings they wouldn’t be allowed back, but that didn’t quell the crowd.

At 11:30 p.m. he ordered his guards to let the East Berliners through. The other checkpoint commanders shortly followed suit. The Berlin Wall no longer divided East and West Berlin. Between 1961 and 1989, 161 people had died trying to cross it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.