Bernanke Explains New Fed Guidance, Confusing Reporters and Self

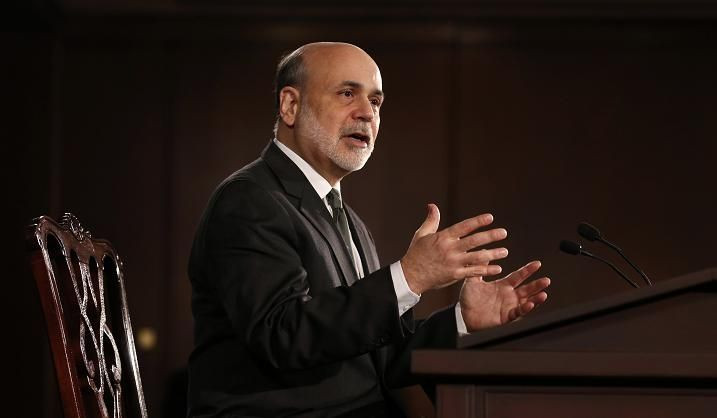

At one point during the nearly 90 minutes that Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke spoke to reporters Wednesday, following the culmination of a two-day meeting of the U.S. central bank’s powerful rate-setting committee, he found himself having to answer if the Fed had done “everything it can” to help stanch America’s unemployment crisis.

“If we could wave a magic wand and get unemployment to 5 percent tomorrow,” Bernanke said, “obviously we would do that.”

Reality, alas, is not so simple.

Indeed, just how complicated policy-making has become for the U.S. central bank was the underlying theme of Bernanke’s press conference Wednesday, where the chairman did his best to explain the unprecedented move the Fed had taken just hours before, announcing it would tie the future direction of its rate policy to a specific unemployment threshold.

In a statement out just after midday, the Fed said it would keep its remarkably low benchmark interest rates for the moment and believed "this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent."

With some reporters still seemingly struggling to digest the significance of the announcement, Bernanke made a couple of explanatory statements that paradoxically made the Fed’s new position both more explicit and more confusing.

First, expanding on an issue that was not directly addressed in the statement, Bernanke noted the new numerical threshold would apply only when deciding which way the Fed’s conventional rate-setting policy lever should be moved. When deciding what direction to take with its more unconventional policy tools, Bernanke said, the central bank would continue to use “qualitative indicators.”

In other words, the Fed is now saying it is treating two parts of its loose monetary policy strategy, near-zero interest rates and asset purchases, as separate tactics.

“The asset purchases and the rate increases have different objectives,” Bernanke explained, later noting “the goal of the asset purchase program is to increase the near-term momentum of the economy,” while benchmark interest rates were more a way to promote long-term stability.

Bernanke also clarified, again making things more complicated in an effort to make them more explicit, that the novel use of the unemployment measure in deciding when to use the benchmark interest rate lever was not absolute. The Federal Open Market Committee would look at other factors of the employment picture, including “payroll unemployment, hours worked and the labor force participation rate.”

Finally, the chairman explained, inflation considerations would play a role in the Fed’s decisions, as always, but it would be future inflation expectations, not current ones, the central bank would be looking at.

“Just to be clear,” Bernanke said in a statement that was anything but, “the projection that matters for our determination is the one that we come up with.”

Nothing To See Here

Interestingly, Bernanke attempted to downplay the significance of the announcements being made Wednesday, insisting to reporters that the change was just in the technical space of communications policy, meant to transmit the Fed’s intentions to the markets in a “more transparent and efficient” manner, but that the move itself should not be considered additional stimulus beyond anything announced in previous months.

“I think this is a continuation of what we said in September. That’s what we’ve done today: follow through with what we’ve said,” Bernanke noted.

More likely than not, however, the Fed’s new guidance will result in more stimulus being pumped into the economy than what was indicated previously. As of its last meeting, the central bank had noted it expected to keep a highly accommodative rate stance until at least mid-2015. The new regime, given that even Federal Reserve economists see the economic outlook worse than it was a month ago, likely means ultra-low interest rates will prevail past that date.

Bernanke's assertion that the moves being announced Wednesday were not more stimulus per se also clashed with an answer he gave to a reporter from MarketWatch who asked him, essentially, if the Fed was contemplating an end game to its policies three or four years down the road.

The fact the situation will continue to become more complicated the longer the U.S. economy continues recovering in an underwhelming fashion “actually is an argument for being more aggressive now,” Bernanke noted.

“Auto-pilot”

That wasn’t the only contradictory statement Bernanke made at the press conference. In the prepared remarks that kicked off the event, Bernanke said the central bank’s new guidance “by no means puts monetary policy on auto-pilot,” as he went on to detail all the variables that served as caveats to the policy.

But in later questions he suggested the policy had an element of being an “automatic stabilizer.” In fiscal and monetary policy, automatic stabilizers are rule-based injections or contractions of the money supply that are supposed to work in a mechanistic fashion once certain numbers are hit, regardless of policymakers’ desires.

He later answered a question from a Economist reporter noting the new policy was somewhat like the “Taylor rule,” which robustly ties benchmark interest rates to measured inflation, again ignoring any wishes central bankers might have in setting rates at specific points in the future.

Catching his own mistake, Bernanke drily noted: “I’m about to get a call from John Taylor,” the Stanford University economist after whom the rule is named.

Going Off The Cliff

Discussing topics of a more straightforward nature, Bernanke was asked at various points Wednesday about his opinions on the current debate over the "fiscal cliff," to which he referred obliquely during prepared remarks when he asked lawmakers to proceed “without adopting policies that could derail the current recovery.”

Bernanke took umbrage to the suggestion from a reporter that the term “fiscal cliff,” which the chairman coined in February, was overly dramatic, saying he didn’t “buy the idea that short-term descent off the fiscal cliff would be not costly.”

He also reiterated that while the Fed might be able to help the economy “on the margin,” overall “we want to be clear: we cannot offset the fiscal cliff.”

Being clear, to Bernanke’s credit, is something he might not have accomplished on specific points Wednesday, but seemed to achieve at a higher level.

During a convoluted discussion with a reporter, he noted the economic dogma that “the central bank cannot control unemployment in the long run,” but then went on to suggest there were caveats to that rule: Allowing unemployment to fester while standing idly by could cause the long-run rate of expected unemployment rate to change. Standing by is not an option.

The point was crystal. The Fed believes the current unemployment crisis is “an enormous waste of human and economic potential,” and while seemingly constrained to acting slowly, carefully, and in a saw-toothed pattern, it still has only one goal: “a return to broad-based prosperity.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.