Bernanke: We Love The Banks, We Are Not Europe

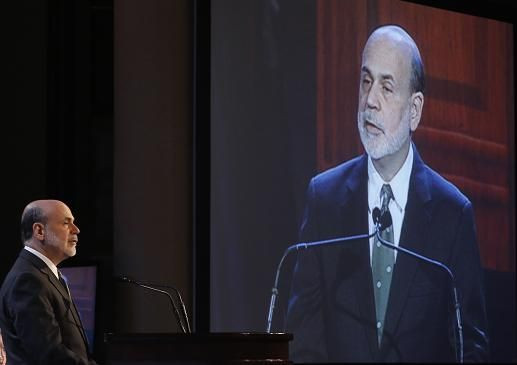

A question-and-answer session between Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and Harvard University Professor Martin Feldstein on Tuesday cast light on Bernanke's approach to decision-making. In the give and take after a speech Bernanke gave at a meeting of the Economic Club of New York, he revealed himself as a cautious strategist, one who exercises a high degree of analysis before implementing market-shaking policies, but also as a person of little self-doubt who doesn’t change his mind after charting a course.

Feldstein's questions for Bernanke addressed most of the issues the Federal Reserve has dealt with recently and, while he was polite, he drilled down to the core of some of the trickiest problems that institutions have faced in the past few months.

The Harvard economist began by asking Bernanke why it seemed that the Fed was having trouble deciding on an effective communication strategy, something that the institution admitted it has continually striven to improve over the past few years, and which -- according to official minutes -- took up much of the discussion time during the bank’s monthly rate-setting committee meeting in October.

“As a general matter, when our main policy tool [of moving interest rates] goes to zero, one of the main tools we have is providing guidance as to where it will go,” Bernanke noted. He explained further that “qualitative language” has proved insufficient, and “more recently we’ve begun to talk about dates. The difficulty with dates is that it mixes two issues: How long does the Fed believe the economy is going to need aid, and secondly, what is the Fed going to do about it.”

Bernanke was even more skeptical about the value of targeting “specific numbers” in terms of inflation and unemployment as a way to provide more robust signals to the markets.

“This is something we’re looking at very carefully. We have to ask, ‘Can we summarize those conditions with two or three numbers?’ And even if we could, would we be able to agree on what those numbers would be?” Bernanke explained.

“Intellectual Point Of View”

Feldstein then asked Bernanke what the central bank could do about overly tight lending standards, which the Chairman had claimed in his speech were affecting the economy adversely as “the pendulum appears to have swung too far.”

Bernanke gave a meandering answer that suggested the best the Fed could do was provide banks with an extremely attractive arbitrage opportunity through low rates and then make sure other government agencies did not get in the way.

“As the profitability of mortgage lending goes up [due to the low levels banks can borrow at], we will see banks” begin to ease lending standards, Bernanke explained.

He also suggested that the Fed’s supervisory and regulatory status atop the banking industry had “at the margins” been to help the housing market, as in cases where the Fed ostensibly pushed banks to execute short sales rather than foreclosure on distressed mortgage debt.

However, seemingly unconvinced with his own answer, Bernanke fell back to saying that the Fed, while not necessarily directly addressing the issue, “had a lot of influence from the analytical, intellectual point of view.”

“We’ve been influential in talking to other agencies, talking to the Congress in providing ideas and approaches,” he said.

“An Interesting Experiment”

A third question by Feldstein addressed one of the topics that has been brought up constantly by wonkier Fed watchers: Why doesn’t the institution, in an effort to further ease the rates environment, bring the reserve rate it pays out to depositor institutions to zero.

Bernanke explained the central bank had done a “cost-benefit analysis” of such a move, and he just didn’t believe moving rates “a few basis points lower” to be worth the risks of completely upending the overnight deposits market.

“If there is no return on overnight money, a variety of institutions may become more illiquid,” Bernanke said. He politely dismissed such actions, which have been taken by European central bankers, as “an interesting experiment.”

“It’s hard to judge what effect that has had," he said. "I think it’s wrong to think of this as a major tool that’s been unused.”

“Do No Harm”

Finally, Feldstein asked Bernanke about one of the main issues he tackled in his speech just a few minutes before, what the Chairman named the so-called fiscal cliff of spending cuts and tax increases that Congress is looking to avoid before the beginning of next year. Bernanke surprised some in the audience by suggesting that policy makers should make a deal -- any credible deal -- rather allowing the economy to go over the cliff.

“We’ll see what kind of deal comes out, but you’re correct that even if some extreme scenarios are avoided, some plausible scenarios involve relatively contractionary policy. It’s up to Congress and the President to figure out how they want to make the trade-off.”

“My advice on this is: Do no harm … we need to avoid the full force of the cliff.”

Then, answering the unasked question of what the Fed would do if politicians passed the buck on the issue, Bernanke said something that made every reporter in the press box go into a typing frenzy: “We will do our best to provide support to the economy, but the ability of the Fed to offset headwinds is not infinite.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.