BP Oil Spill: Louisiana Wetland Loss Is Speeding Up Due To Crude From Deepwater Horizon Disaster

NEW ORLEANS -- Once Wendy Billiot’s kids got big enough, the family often took fishing trips in Louisiana’s southern marshes. Time and again, she noticed a strange quirk in her boat’s GPS system: Land that appeared on the digital maps didn’t actually exist in the real world. That’s when she came to the realization that Louisiana is sinking.

“It says there’s a swath of land, and I’m looking, and I see water. And so you go, ‘Where did that land go?’” recalls Billiot, who runs a tourism business in Theriot, a town along the Bayou Dularge 70 miles from New Orleans. “That was in the early 2000s. That’s when I really started paying attention.”

Billiot soon learned that southeastern Louisiana has steadily lost its wetlands since the 1930s. Levees on the Mississippi River and dredging by oil-and-gas companies permanently altered the area’s environmental makeup, causing destruction of the wetlands.

It’s gotten worse in the past five years. The BP oil spill, which began pouring hundreds of millions of gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico April 20, 2010, has accelerated land loss along the Louisiana coast. Even before the deadly explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, geologists warned the state was losing a football field of land every hour, or 16 square miles a year. Now, oil-soaked marshes and barrier islands that would’ve taken decades to erode have nearly vanished in just a few years, ecologists say. The Gulf’s dramatic advance is increasingly exposing millions of residents to hurricane-fueled storm surges and damaging floods.

During the spill, “you’d see vegetation be coated with oil, and it would pretty quickly die, and the wetland itself would erode back,” says Alisha Renfro, a coastal scientist with the National Wildlife Federation in New Orleans. “You saw again and again that wetlands seemed to be disappearing really quick” -- and they haven’t stopped their vanishing act. “How long this accelerated erosion rate will last is still unknown,” she says.

In Barataria Bay, a 12-mile-wide bowl of brackish waters, Cat Island serves as a stark example of the oil-related decay. Before the spill, the mangrove patch was a 40-acre nesting ground for brown pelicans and shorebirds. But when thick crude crawled across the bay and swarmed the island’s shores, the mangrove roots rotted and the birds’ habitat disappeared. Now, all that’s left is a streak of sand, and a few dead branches.

Simone Theriot Maloz, a local conservationist, says she’s not sure Cat Island is worth rebuilding, given its rapid descent. “Five years later, we’re having to think about what is just lost,” she says, looking out at the sandbar from the bow of a fishing boat. Bottlenose dolphins dive nearby as the engine gains speed, although their presence is deceiving: In areas affected by the spill, dolphins now die at four times their historic rate.

Maloz is the executive director of a group called Restore or Retreat. When the organization was formed 15 years ago, the name was initially meant as a threat to coastal residents: “Restore, or you’ll be forced to retreat” to northern Louisiana or beyond, she explains. But with wetland loss speeding up, far outpacing restoration efforts, “restore or retreat” is no longer an ultimatum. “Now, it’s a legitimate question,” she says.

BP PLC executives officials dispute the contention that the Gulf is getting worse. “Extensive investigations of marshes show they are experiencing significant recovery,” the company said in a March report. Oil-stained beaches have also largely recovered, “and the amount of shoreline that was heavily oiled decreased rapidly and dramatically due to cleanup operations and natural processes,” the firm said.

Federal scientists and environmental groups have criticized BP’s statements, saying the energy company “misinterprets and misapplies” data about the Gulf’s post-spill recovery. “From decades of experience with oil spills, we know that the environmental effects of this spill are likely to last for generations,” the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said in response to BP’s report.

Louisiana’s changing landscape has critical implications for Gulf Coast residents, who are losing their first line of defense just as sea levels rise due to global warming. The crabs, fish and oysters that people here depend on to earn a living and feed their families are becoming less available as habitats disappear. And, as homes become more exposed, flood-insurance costs are soaring and new building standards are growing cumbersome.

Yet the predicament isn’t Louisiana’s alone. The entire U.S. depends on the region for much of its energy and commercial shipping. Louisiana is home to about one-half the country’s oil-refining capacity, and more than one-quarter of U.S. waterborne exports move through one of the state’s five major ports. A sprawling network of pipelines here serve 90 percent of U.S. offshore energy production and about one-third of the nation’s total oil-and-gas supply.

“It’s a national problem,” Billiot says, “but the majority of the nation isn’t even aware.”

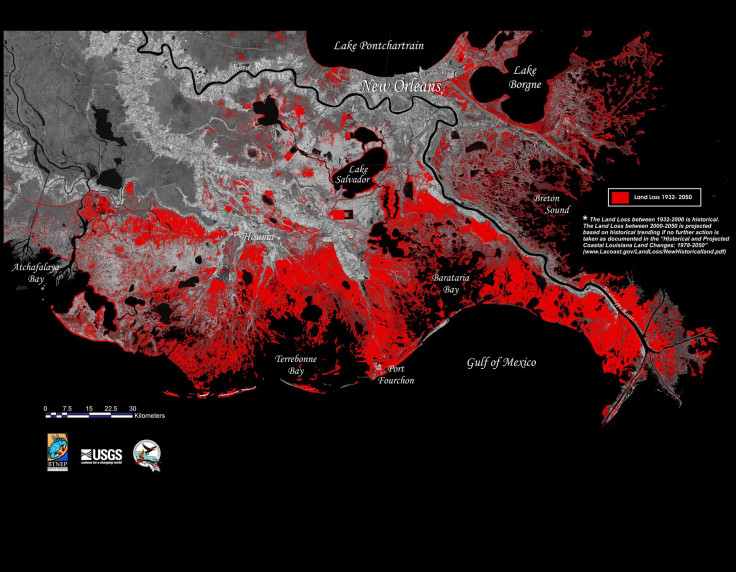

Since her realization, Billiot has devoted herself to educating locals and visitors about wetland loss. She published a children’s book in 2005 called “Before the Saltwater Came,” which explains how canals -- dug for oil rigs and to control river flows -- have allowed saltwater from the Gulf to overpower freshwater marshes and swamps. The influx of salinity is killing plants and trees, whose roots are needed to hold the soil intact. Billiot later earned her captain’s license so she could guide boat tours throughout coastal Louisiana, which since 1932 has lost more than 1,900 square miles of land, a mass roughly the size of Delaware, the U.S. Geological Survey estimates.

The consequences of land change are already evident in low-lying communities such as Theriot, which sits just 21 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. Billiot remembers how the town was slammed by Hurricane Rita in September 2005. Rita produced a nine-foot storm surge that, by the time it reached Theriot, caused five feet of flooding. Billiot’s home is only four feet off the ground and was soaked. Yet if the area’s original marshlands were still there when Rita hit, the surge would’ve fallen to just two feet of water, and her house would’ve been spared. “The healthy marsh was our natural protection, and it’s gone,” she says.

As the risks of flooding rise, so too are the costs of living near the water. In recent years, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Flood Insurance Program has raised premiums for millions of policyholders nationwide. In April, rates are poised to jump again as FEMA seeks to cover its $24 billion debt, more than one-half of which resulted from Hurricane Katrina. Under a plan approved by Congress, homeowners with federally backed mortgages and in high-risk flood zones could see rates climb by as much as 18 percent a year, potentially a difference of thousands of dollars.

In Grand Isle, a tranquil beach town on the Gulf, “For Sale” signs hang from empty homes and rentals propped up on 12-foot-high posts. The exodus was partially prompted by the BP oil spill, which hit the island especially hard and drove tourists out for several years. However, insurance rates are also making property unaffordable, and some residents are simply cutting their losses, says Jean Landry, a Grand Isle resident and a local program manager with the Nature Conservancy.

“If you drive through the island, you see a lot of places up for sale, and it’s because their insurance is too high,” she says while on a porch seat facing Louisiana Highway 1, which connects Grand Isle to the mainland. For some homeowners, the monthly insurance premium costs just as much as the mortgage, resulting in payments of as much as $4,000 a month, she says. Two of Landry’s sons recently sold their properties in Grand Isle because of the soaring expenses and liabilities. “Our young people who could trace their roots back here 200 years can’t afford it,” she says.

Repairing a building after a flood or storm is similarly growing more expensive. To get state or federal disaster relief, property owners must meet strict guidelines designed to make buildings more resilient, such as elevating homes, installing wind-resistant roofs or putting in first-floor flood vents. Some owners are finding it easier to move out of the high-risk zones and away from the Gulf.

In Theriot and surrounding municipalities, school boards are opting to move elementary schools farther north rather than repair damaged buildings. Supermarkets, post offices and other community staples are also relocating. While the northern migration is ultimately more sustainable in the long run, given the scale of wetland loss and rising sea levels, Billiot and other residents are beginning to feel stranded.

“We’re what you call a ‘food desert’ down here now,” she says. “The Dollar Store is up the road, and we have a couple little gas stations, but if you want produce and fresh meat, we’ve got to go all the way to Houma” -- a 30-minute drive north. “As you lose these services in your community, you’re almost forced out.”

The move out of the bayou poses tough economic and social challenges to the Gulf region.

Commercial fishermen and oil-and-gas workers need to live on the water to do their jobs, and they’re frequently neither educated nor skilled to work in other types of professions without retraining. Generations of Cajun and indigenous Houma cultures are firmly rooted in close-knit communities, and stand to lose their heritage as residents disperse. Plenty of families simply don’t have the means to pack up and move.

“We as a state and community are having to face the question of what to do for the people who can’t afford to retreat,” says Maloz, the conservationist. “Along with the hard loss of land comes life-changing decisions. Somebody who lived in the same house as their great-grandma can’t pass it on to their kids. How do you move a whole community?”

Down in Grand Isle, Bob Sevin, 77, says he’s focused on enjoying what’s still left.

Sevin is president of the island’s port commission and grew up there. He graduated from the high school with six other students, and his father ran a combination service station-hamburger joint, he recalls, seated by his wife, Joyce, on the patio beneath their elevated home. The couple has four children, seven grandchildren and five great-grandchildren -- most of whom now live in Texas and work in the oil-and-gas industry.

Sevin expects the BP oil spill will affect the island for decades to come, by eroding its shoreline and its impact on the fish. “I was hoping the great-grandkids could be out here when they get my age,” he says. “But I don’t know if the island will still be here then.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.