Brazil Economic Crisis: Rousseff Impeachment Talk Grows, But Potential Presidential Replacements Garner Little Enthusiasm

After enduring months of public pressure to step down from office, Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff is now facing lawmakers’ most serious moves yet toward her impeachment. Members of Brazil’s main opposition parties formally discussed impeachment procedures for the first time this week and backed a request to start proceedings against the embattled leader over allegations that she doctored government accounts to boost her electoral chances last year.

With talk of Rousseff’s potential impeachment again at a fever pitch, Brazil’s political trajectory, which will heavily determine how officials combat a painful economic recession this year, is anything but certain. Rousseff’s public support has badly deteriorated this year over criticisms of economic mismanagement and widening corruption probes, eroding her political ability to pass needed measures to combat the crisis. But even if she does leave office before her term expires in 2018, there are no current presidential contenders that are likely to shore up enough confidence to lift the country out of its economic doldrums soon, analysts say.

“There is no person at this moment that would present a strong sense of hope for the population,” said Bernardo Sorj, director of the Edelstein Center for Social Research, a think tank based in Rio de Janeiro.

Helio Bicudo, one of the founders of Rousseff’s Workers’ Party, filed a request in the lower house of Congress Thursday to initiate an impeachment trial against Rousseff. The motion, backed by Brazil’s opposition parties, is based on allegations that she padded public accounts with funds from state banks to boost the government budget in the run-up to her re-election in 2014. A federal audit court is reviewing whether she violated fiscal responsibility laws and is expected to issue a ruling next month.

Impeachment requests have been filed before and failed, but the request from Bicudo, a prominent activist who left the Workers’ Party in protest of alleged corruption within the party in 2005, indicates that the push to remove Rousseff from office is reaching new heights. The request needs support from two-thirds of the house, or 342 lawmakers, to open a trial against the president. Opposition groups say they have 280 votes so far, so it remains unclear if the motion will succeed.

If Rousseff does leave office, the next president would be in charge of pushing through tough economic measures to pare down Brazil’s public debt and undertaking longer-term reforms to get the economy back on solid footing. The country’s gross domestic product is on track to shrink by 2.2 percent this year amid falling demand for exports, precipitated by an economic slowdown in its largest trading partner, China, and a blistering corruption scandal in state-run energy company Petroleo Brasileiro (Petrobras) that has damaged investor confidence. Brazil is also scrambling to close a gap in the 2016 government budget through a series of tax hikes and spending cuts.

Building political consensus will be critical in getting the economy back on track. Rousseff’s approval ratings, now at just 8 percent, and severe lack of public trust have badly tarnished her ability to pass through proposed cost-cutting measures and longer-term reforms like shrinking Brazil’s pension system, as opposition lawmakers have resisted a host of proposals.

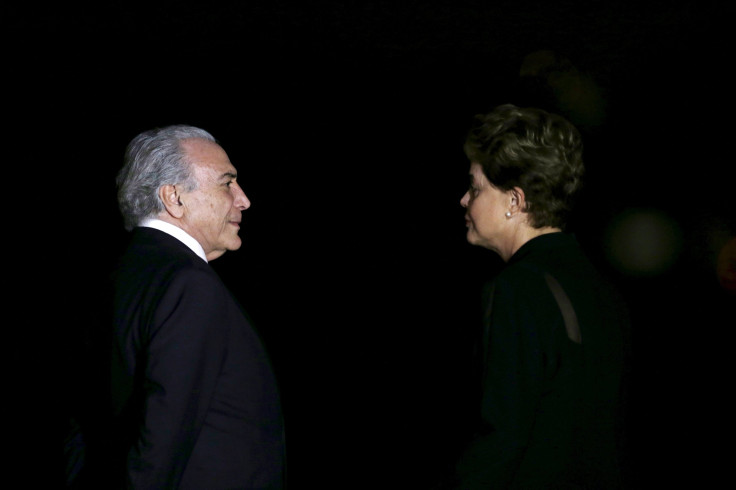

If an impeachment move is successful, the rest of her presidential term would be in the hands of Vice President Michel Temer, a seasoned politician and leader of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, one of the main allies of Rousseff’s Workers’ Party. But it’s unclear if opposition lawmakers, some of whom are considering presidential bids in 2018, will coalesce around Temer on unpopular economic decisions.

Even if he does manage to temper political fractures in Congress, Temer doesn’t have a strong economic team behind him at the moment, said Marcos Troyjo, director of the BRICLab forum on emerging economies at Columbia University in New York. “On the one hand, you might have a political crisis relaxed, but you don’t have economic expertise available,” he said in a recent interview.

Temer himself may face a corruption investigation over allegations that he and Rousseff both used funds connected to the Petrobras scandal in their 2014 re-election campaign. A judge from Brazil’s electoral court last month requested federal prosecutors open a probe of the campaign, although authorities have not yet greenlit the process. If a ruling finds they used illicit funds, both Temer and Rousseff could face impeachment proceedings.

#Temer quietly observes pro-impeachment movements in #brazil. If #dilma leaves he will be the main beneficiary. pic.twitter.com/UUxOdRJ7Xx

— Evodio Kaltenecker (@Evodio_Kalt) September 11, 2015

That would leave the presidency temporarily in the hands of Eduardo Cunha, the speaker of the lower house of Congress who is also facing charges of involvement in the Petrobras scheme, until new elections can be called.

The Brazilian Social Democrat Party, Brazil’s primary opposition party, would have an advantage in those elections. The party is split among three leaders: Aecio Neves, an economist who challenged Rousseff in the 2014 election; Geraldo Alckmin, the governor of São Paulo, and Jose Serra, a senator who previously ran for the presidency in 2002.

Neves, who lost his 2014 presidential bid by just three percentage points, previously rallied investor confidence with market-friendly proposals and pro-business sentiment. But he still may not garner much enthusiasm among Brazilians, said Sorj of the Edelstein Center for Social Research.

“Aecio doesn’t command such respect in public opinion,” Sorj said, adding that Alckmin lacked charisma, and Serra did not have strong support from within the party.

Sorj said the current impeachment requests in Congress weren’t likely to get enough votes to pass through. But the calculus could change in the coming months, particularly if public demonstrations against the president swell to large enough numbers to put additional pressure on lawmakers.

“What will make a big difference is what will happen in the streets,” he said. “That will define the possibility for impeachment, because I don’t see Dilma renouncing her position.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.