Breathing Space: Why China's Population Worries About Air Pollution But Ignores Climate Change Talks In Paris

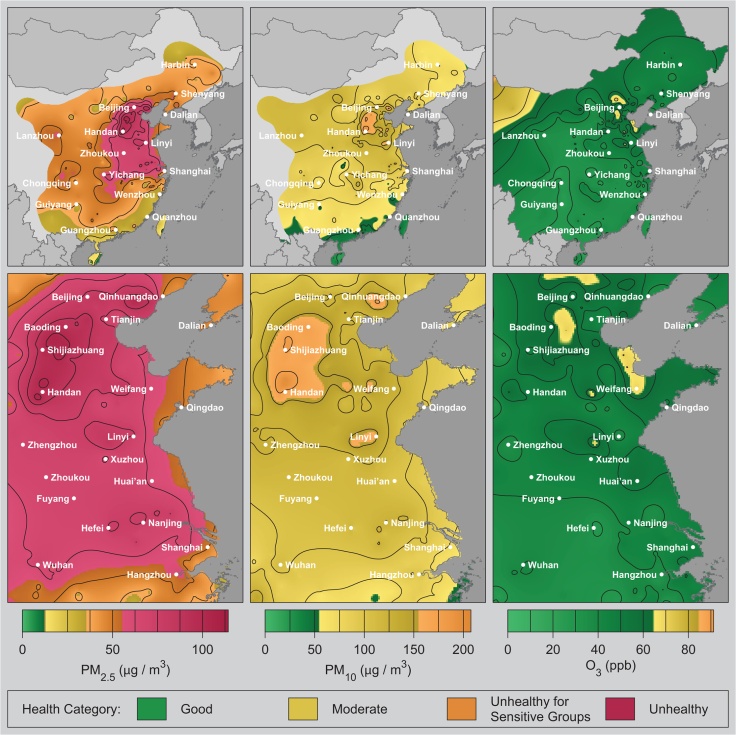

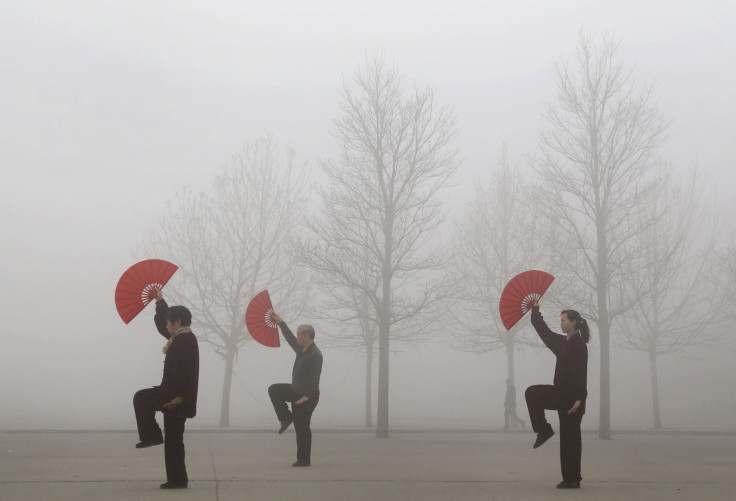

SHANGHAI -- As Chinese officials take part in the climate change negotiations in Paris, the issue could hardly seem more urgent back home. After several days of choking smog-blanketed Northern China last week -- particularly the capital Beijing, where the concentration of dangerous fine-particle pollutants in the air was off the end of the scale -- the Beijing authorities have now declared their first ever red alert for pollution, shutting down construction sites and restricting private car use to odd and even license plate numbers on alternate days.

It's a far from isolated event. Such pollution, caused by rising car use, coal-fired power plants and construction on a vast scale, has been a continuing problem in recent years, leading to heightened public concern. Air quality is top of people’s worries in many surveys, millions carry face masks as a matter of course, and sales of air purifiers have gone through the roof. Environmental protests, mostly about chemical or refuse-processing plants that people fear will damage the air or local environment, have become increasingly common.

Yet when it comes to climate change and its potential impact, Chinese people can seem relatively unconcerned. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center suggested only 18 percent of Chinese respondents saw this as a major issue of concern -- down some 23 points compared with 2010, shortly after the last Climate Change Summit in Copenhagen. Pew said Chinese people were the least concerned about the topic of the 40 countries surveyed.

The survey did find that over 70 percent of Chinese respondents supported a global climate change deal, but the relative lack of concern suggests public pressure on the government to reach a deal in Paris will be lacking. China has said carbon emissions will peak in 2030, but verification remains a sticking point, and Beijing has also called on developed countries to do more to help others, particularly in terms of technology transfer.

In Shanghai, China’s financial capital, pollution is generally less severe than in Beijing, but it still reached levels 10 times those considered safe by the World Health Organization last week. And the low-lying coastal city will be partially submerged if climate change is not slowed and temperatures rise further over the next century, environmentalists say. But local residents remain sanguine.

Deng Yimei, a saleswoman in her 50s, lives in the city’s Pudong region, close to the sea. She’s worried about pollution, she says -- she takes the subway, uses an electric bicycle and energy-saving lightbulbs -- and turns on her air conditioning only when the temperature gets above the mid-30s Celsius. Yet she shrugs at the mention of rising oceans: “Well we haven’t been submerged yet,” she jokes. “I live on the 25th floor; I doubt we’ll be submerged! Anyway I won’t be here in another century.”

Richard Brubaker, visiting professor of sustainability at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai, says many people in China, as in other countries, tend to pay less attention to the wider issues such as temperature rises or toxic carbon emissions:

“The debate about carbon emissions has always been positioned internationally as being about saving polar bears, saving the world,” he says. “These emotional icons that we’ve thrown up are not what people in China care about; they're about saving somebody else. And for people in China, that puts it into the category of 'Somebody else will fix it; it’s the government's job to take care of things like this.' People feel unempowered about such issues,” Brubaker adds. “But they care about the everyday, tangible problems that affect their family, themselves, at home in their office and on the street.”

That’s how it feels to Zhou Jiliang, a Shanghai resident in his early 40s.

“I’ve heard about the warnings of rising sea levels," he says, "but for the moment the main thing I wish for is to see more blue skies in Shanghai. People like us don’t have so much time to pay attention to the conference in Paris.”

Still, Zhou says he hopes the government can contribute to solving environmental problems -- he runs air purifiers all the time in his home because of worries about air quality. And he’s pleased that the local authorities have introduced free public bicycles in the suburb where he lives. He also feels that his neighbors are using their cars less these days. “There’s so much in the media about air quality and using public transport, it would be silly not to follow this advice,” he says.

Deng, the saleswoman, is less sure about any change in lifestyles: “So many people in Shanghai are buying cars -- can you stop them?" she asks. "It’s like buying a house. People in Shanghai like to show off their wealth, to compete with others."

However, she says, the young generation is thinking more about the issues. And her colleague Li Weifang says attitudes will change:

“People like modern things, but now in Shanghai they’re concerned about water, air, food safety," Li says. "This is what people will take most seriously in the future. The most valuable thing is your health; it doesn’t matter how much money you have.”

Brubaker says one major difference in China these days, compared with five or six years ago, is the availability of data. Social media and the spread of smartphones, with apps measuring air quality, mean people are far better informed about the scale of pollution. However, he says, that may be one reason why they’re less concerned about bigger-picture issues now:

“At the time of Copenhagen this was such a big issue in China, everyone was saying we must do something," he recalls. "But why were young Chinese people so concerned then? At that time they didn't feel they were facing a big crisis of their own -- they were coming out of the 2008 Olympics [when Beijing's air improved after a series of government measures]. So there was more public pressure on the issue of carbon emissions in 2009 than now, partly because people were less worried about air pollution. They had the luxury of worrying about somebody else’s problem then. Now they've got their own problems!”

But some are watching events in Paris closely, and say the Chinese government can and should do more than at Copenhagen, when it was criticized by the West for rejecting specific emissions targets.

“At the time of Copenhagen we felt that China and India were being bullied by the West,” says Cecilia Zheng, a Shanghai-based university student in her early 20s. ” It was very dramatic, a big division. We felt the West was evil, putting unfair pressure on developing countries. So it caught people’s attention."

This time, she says, the problems are so serious that “we can see that the Chinese government should do something.”

Zheng still thinks the West should do more to transfer environmental technology to countries like China: “It’s unfair if they don’t; this can benefit all human beings,” she says. But she also says the Chinese government is now capable of contributing too: “I was just watching the news about China's leaders visiting Africa. We’re investing a lot of money in Africa,” she says. “I think we can also afford to spend money on the environment. We’re not so poor now.”

Zheng, however, is disillusioned about the attitudes of some young people concerning environmental problems. It’s understandable that older people are “more numb, more passive” about these issues, she says. “But lots of young educated people just make jokes about the bad air. And they’re all just focused on finding jobs, and everyone wants a car.” She says young people have been put off taking action on the environment because they’ve read a lot in the media about local governments protecting polluting enterprises and therefore feel “they can’t intervene -- but I believe you can.”

But Zheng herself may soon take a different kind of action. She previously joined what has become a growing flow of people moving from the North of China to the South, attracted in part by the promise of better air quality. Yet though she was initially impressed by Shanghai, where she studies, her attitude has since changed:

"I used to think that Shanghai was heaven compared to Northern China," she says. "But recently I got a bad allergy, and the doctor told me it was connected to air quality. He said a lot of people get it. It’s affected my immune system. So I feel that emissions have seriously influenced my life. And this has changed my mind about where I want to be. I’m thinking of moving to Australia in the future."

She’s not alone. Chinese media have recently discussed the phenomenon of students moving abroad to escape the smog. One recent survey of Shanghai university students, by local sustainability consultancy Collective Responsibility, found that more than a quarter were thinking of going abroad due to air pollution, while around 60 percent said “they would be uncomfortable bringing up a child in Shanghai due to the pollution,” according to its research manager, William Morris.

Zheng wouldn’t be the only educated individual, with a desire to improve society, to leave China due to this growing problem. Louis Wu, a designer and architect in his 30s, has already blazed the trail to Australia. After spending many years working on design projects in China’s big cities, last year he decided that his future lay outside China. He says social welfare and education for his child were among the reasons that led him Down Under, but the biggest factors were environmental.

“[Australia] is a country that protects the ecology better,” he says. “It’s a place that cares for the environment, cherishes nature, where the relationship between people and nature is more harmonious. Of course some things are less convenient here for us, but we’ve fallen in love with this place.”

The associated costs of losing young, talented individuals is something else the Chinese authorities will need to factor in when calculating their financial commitments to tackling climate change and the blight of smog.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.