Brexit: If Britain Quits The EU, What Then?

Britain has never been too keen on getting closely involved with Europe. When Germany, France, Italy and the Benelux countries established the European Coal and Steel Community in the 1950s, the start of what became the European Union, the British turned down the offer.

As this single market evolved into a much wider common market covering a whole range of goods and services, customs duties among the six founding countries were completely abolished and common policies, notably on trade and agriculture, were also put in place. In 1973, Britain finally felt it made economic sense to join.

Video: The Schuman Declaration of May 9, 1950.

Forty years later, the UK is having second thoughts about the costs and benefits of its European Union membership. Back then, Europe was an economic powerhouse; today, it’s mired in recession.

Prime Minister David Cameron, who had resisted calls to hold a referendum on membership, finally bowed to pressure last month by promising to give Britons an in-or-out choice on whether to remain in the 27-nation bloc by the end of 2017 -- provided he wins a second term.

An anti-Brussels sentiment appears to be sweeping through the British public. Only one in three Britons would vote to stay in the bloc, a Financial Times survey by pollsters Harris Interactive found. The results are based on a survey (conducted between Jan. 29 and Feb.6) of more than 2,000 people.

The popularity of the EU across Europe is also at an all-time low. A separate poll conducted by its own European Commission found that only 33 percent of Europeans trust the EU.

“The UK leaving the EU is arguably not in anyone’s interest, but without that threat, negotiations become toothless,” said Nawaz Ali, UK market analyst at Western Union Business Solutions.

What Is The UK Looking For?

“The UK is looking for a ‘political champion’ in Europe, someone credible, a Churchillian figure, to jump on their horse and say ‘follow me,’” said James Berkeley, director of the consultancy Berkeley Burke International based in London.

“It wants European leaders to use a telescope, not a microscope,” Berkeley added. “Don’t try to gradually inch your way forward from today. Think of the future and work backwards.”

It may be premature to say that Britain wants to quit the EU per se, as there are vocal groups on either side of the debate, but much of this debate is being colored by the view that the union's powers are expanding through crisis management as opposed to more natural evolution.

In fact, what the UK would really like to do is pull back until its relationship with Europe becomes one based on free trade, with the minimum necessary regulation.

In a U.S. TV interview in December, Chancellor George Osborne said: “Britons want to be in Europe, not run by Europe.”

“We are happy to be part of a single market, we are happy to be part of a free trading zone, we are happy to have the policies that come around that – and indeed other polices that are part of the EU -- but we are not part of your single currency, we do not need to be part of your ever-closer union, and there are things that we want back,” Osborne said, according to The Telegraph.

Impact Of An Exit

If Britain decides to leave, it could grab a few benefits quickly. The nation would save about £8 billion ($13 billion) a year in net budget contributions to the EU, as well as roughly £30 billion a year in EU-related red tape costs.

The British Chambers of Commerce said in its latest Burdens Barometer report available that almost a third of the country's regulatory burden came from European Union directives in 2010.

The study suggests that the cumulative costs (1998 - 2010) to UK businesses from EU-origin regulations implemented since 1998 is £60.8 billion, which accounted for 69 percent of the total net cost of dealing and complying with new laws and regulations during the 12-year period.

“Leaving the EU would be a mistake; it would hurt the UK,” warned Laurent Jacque, a professor of international finance and banking at Tufts University’s Fletcher School. A British exit would dent trade with a market that accounts for half of Britain’s exports.

While there is active debate about whether the net impact of EU membership is positive or negative, any of the benefits the UK might gain from leaving (less regulation, more competition, no contributions to the EU budget) would not start to accrue until it had actually left, which even if it happens, is still many years away.

Perhaps the main immediate economic consequence of that stance is that uncertainty around Britain’s membership could persist for nearly five years. That could potentially hinder investment into the UK if access to the European single market and the UK’s contribution to shaping the EU are seen as important attributes. It seems unlikely that there will be any extra investment flowing into the UK on prospects it may leave the EU, given that the situation is so uncertain.

Estimates from the EU suggest that Britain’s access to free trade within the community could be worth around 0.1 percentage points to 0.2 percentage points per annum to UK trend growth.

Once the UK leaves the EU, British dairy exports would incur an import tax of 55 percent to reach the European market, with tariffs on some items of more than 200 percent -- making these products much less competitive. Average tariffs on clothing would push up their price in European markets by 12 percent.

The auto industry has been one of Britain's few economic success stories since the financial crisis. But in the event of a British exit, automakers would be drifting away, as they will be looking at a 4 percent tariff on car-equipment sales to the EU and there would be pressure to impose tariffs on components imported from it.

“The UK not only has to be part of Europe. It has to be a fundamentally active part of Europe," said Ian Robertson, global head of sales at BMW and a member of the board of the German company, according to The Telegraph. "To think about the UK being outside of Europe doesn't make sense."

A British exit would also put London’s role as an international financial center at risk. It would begin with a decline in investment and hiring as London suffers relative to cities such as Frankfurt and Paris.

Britain is attempting to become a leading global trading canter for the Chinese renminbi, and putting up a political fence between the UK and the rest of Europe could create a dividing line in financial markets. “Countries like China could dismiss the option of London if it was no longer at the fingertips of every European trader,” Ali said.

“Banks won’t disappear from London overnight, but they will over time if Britain votes ‘no,’” Michael Sherwood and Richard Gnodde, co-CEOs of Goldman Sachs International, wrote in an opinion piece that appeared in The Times of London on Feb. 14.

“While the UK could potentially negotiate various free trade agreements even if it left the EU, that process could nevertheless be very cumbersome and drawn-out,” said Nick Bate, UK economist for Bank of America Merrill Lynch, in a note to clients.

A new political landscape would inevitably change the way trade and finance are conducted.

“Investors would probably explore a different looking springboard to the EU, especially if that connecting path between the UK and Europe went from being less of a high-speed link and more of a toll bridge,” Ali said. “The impact of such a change could be dramatic on a global scale.”

Fragile Economy

Last week, credit rating agency Moody's downgraded its rating of the British economy over fears that growth would "remain sluggish over the next few years."

Data released Wednesday provided a further confirmation of a 0.3 percent quarter-on-quarter drop in gross domestic product in the fourth quarter of last year. In other words, the British economy remains halfway to the unwelcome achievement of a “triple dip” recession.

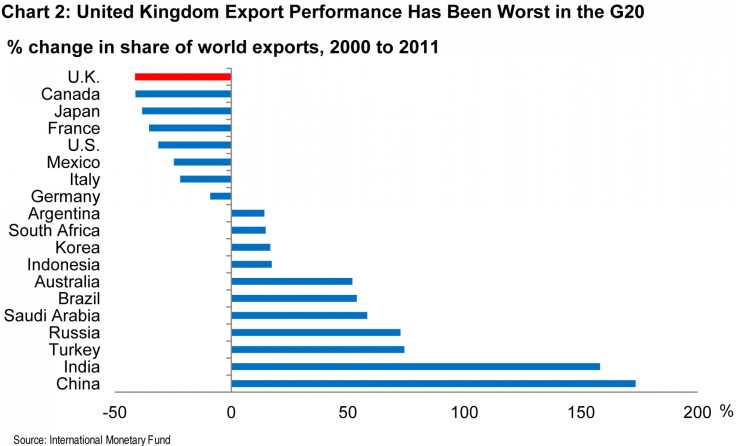

The incoming Bank of England governor, Mark J. Carney, presented an informative chart in this 45-page Q&A that highlighted the sorry state of the British economy. In his first public remarks before Parliament, Carney pointed out that since 2000, Britain’s share of global exports have decreased about 50 percent — the steepest decline among the world’s 20 biggest economies.

That decline is all the more alarming if one considers that it has happened during a time that the pound has lost up to a third of its value against other major currencies, one of the largest currency devaluations in the country’s history. In theory, a cheaper currency makes a country’s exports more attractive for foreign buyers.

Chances Of A Brexit?

Any UK exit will be a “process,” not an “event.”

“It will be a gradual process of redefining the UK and Europe relationship before, during and after the political decisions,” Berkeley said. “An overnight ‘UK exit,’ in the form of a total withdrawal at a fixed time and date from all functions, has zero percent chance of happening.”

Berkeley assigns a 25 percent probability to the UK becoming one of the middle rather than core rings within a redefined “EU solar system.” The most likely outcome, according to Berkeley, is for the UK to become a core member of a redefined Europe – a 70 percent chance.

While nothing is set in stone, one thing is quite certain: Once Britain leaves the room, the door shuts behind it for good.

The Burdens Barometer 2010, from Scribd:

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.