Caribbean People Still Carry Indigenous DNA From Lost Taíno Society

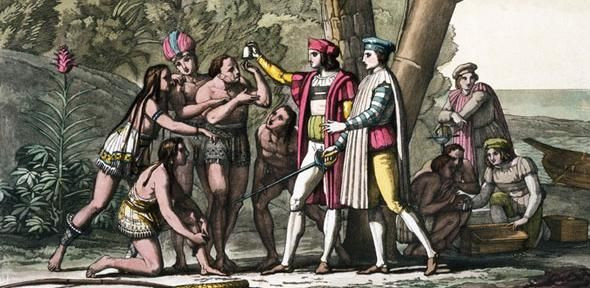

Genetic evidence shows Caribbean people are keeping alive the DNA of the indigenous Taíno, an ancient group that thrived on the islands until Christopher Columbus landed in the Americas and their home was colonized.

Researchers took genetic information from the 1,000-year-old tooth of a Taíno woman found in a cave in the Bahamas and compared it to modern Puerto Ricans, finding a stronger connection between the two than the Puerto Ricans have to any other Native American group, according to a study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The scientists say a similar connection is likely between the Taíno and the modern inhabitants of other Caribbean islands.

The Taíno may have first inhabited the Caribbean islands about 2,500 years ago, eventually spreading to the Bahamas — where they have been known as the Lucayans — a millennia later. The Lucayan tooth used for this analysis belonged to a woman who lived between the eighth and 10th centuries.

In addition to their findings about the genetic connection between the ancient and present-day people, the researchers explain in their study that they also learned more about the origin of the Taíno, pointing to the northern area of South America as their physical roots and saying they “had a comparatively large effective population size.”

Information about how populous their society was comes from analyzing their DNA for signs of inbreeding, which results from procreation being limited to smaller groups. When inbreeding is low, it indicates a larger population where breeding groups were not isolated from one another.

“This is consistent with archaeological evidence, which suggests that indigenous Caribbean communities were highly mobile and maintained complex regional networks of interaction and exchange that extended far beyond the local scale,” according to the study.

One of the key findings of the study is in the connection between Taíno and modern Puerto Rican DNA, which shows genetic continuity that has persevered from the Caribbean’s ancient indigenous people to the current residents. Although this link has been previously suggested, the DNA now backs it up.

“Many history books will tell you that the indigenous population of the Caribbean was all but wiped out, but people who self-identify as Taíno have always argued for continuity,” researcher Hannes Schroeder said in a statement from the University of Cambridge. “Now we know they were right all along: there has been some form of genetic continuity in the Caribbean.”

The roughly 100 Puerto Ricans whose genomes were compared to the ancient tooth’s DNA showed about 10 percent to 15 percent native ancestry that was close to the ancient genes.

One Taíno descendant who worked with the researchers, Jorge Estevez, recalled growing up in the U.S., hearing Taíno stories from his family but being taught in school that his people had already died out.

“I wish my grandmother were alive today so that I could confirm to her what she already knew,” he said in the Cambridge statement. “It shows that the true story is one of assimilation, certainly, but not total extinction. … To us, the descendants, it is truly liberating and uplifting.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.