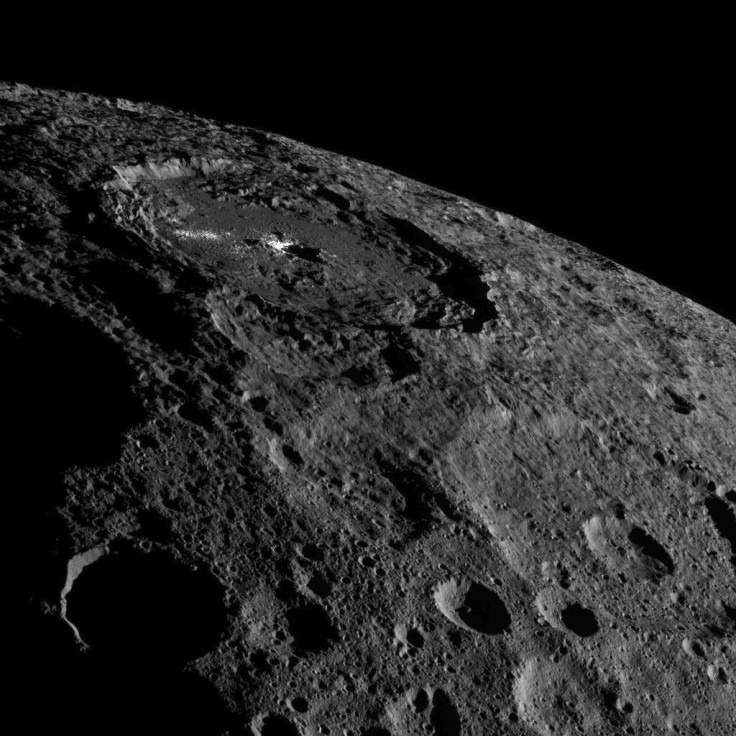

Ceres’ Bright Spots Seen In New Dawn Image

Since March 2015, when NASA’s Dawn spacecraft entered into orbit around Ceres — a dwarf planet in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter — a clump of bright spots on its surface has mystified scientists. Recent studies have suggested that these spots, located in 57-mile-wide and 2.5-mile-deep region known as the Occator Crater, are most likely inorganic salts that were exposed after water on Ceres’ surface vaporized.

Now, NASA has released a fresh image of the crater, captured on Oct. 16 by the Dawn spacecraft. The image, taken when the space probe was carrying out its fifth science orbit — at an altitude of about 920 miles — shows not only its central bright region, but also the secondary, less-reflective areas.

“This image captures the wonder of soaring above this fascinating, unique world that Dawn is the first to explore,” Marc Rayman, Dawn’s chief engineer and mission director at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, said in a statement accompanying the image.

According to a study published in the journal Nature last December, the appearance of the bright material in the crater is consistent with a type of magnesium sulfate — an inorganic salt — called hexahydrite. These minerals are also found on Earth, occasionally at the rim of salt lakes. A different type of magnesium sulfate present on Earth is Epsom salt.

According to this theory, impacts from asteroids might have unearthed the mixture of ice and salt, exposing them to the surface, where they appear as bright spots.

“The global nature of Ceres’ bright spots suggests that this world has a subsurface layer that contains briny water-ice,” study lead author Andreas Nathues, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Göttingen, Germany, said in a statement at the time. “We are currently probably seeing remnants of an evaporation process exhibiting different stages in different locations. Perhaps we are witnessing the last phase of a formerly more active period.”

Dawn, which spent over eight months studying Ceres from an altitude of roughly 240 miles, moved to its current, higher orbit in August. Since capturing the latest image of the Occator Crater last month, the spacecraft has begun maneuvers to move to an even higher orbit of about 4,500 miles from Ceres.

“One goal of Dawn's sixth science orbit is to refine previously collected measurements. The spacecraft's gamma ray and neutron spectrometer, which has been investigating the composition of Ceres' surface, will characterize the radiation from cosmic rays unrelated to Ceres. This will allow scientists to subtract ‘noise’ from measurements of Ceres, making the information more precise,” NASA said in the statement.

Dawn will continue to study the dwarf planet for at least another year. Scientists hope that by observing Ceres during its closest approach to the sun — perihelion — in April 2018, they’d be able to observe significant changes, and even volcanic activity, triggered by the rise in temperature.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.