Chimpanzees Show Disgust Towards Pathogen-Containing Food Like Humans

Chimpanzees are our close relatives. It is widely known that humans share about 95 percent of their genetic material with chimps and bonobos. But, on the surface, the differences are stark. Chimpanzees are much bigger and stronger than humans, are better climbers and have longer hands. We can chalk up several such structural differences, but the similarities are undeniable.

One way humans differ a lot is behavior and language. When humans observe a chimp, they see it ‘monkeying’ around. In fact, the act of flinging poop is exclusively associated with gorillas and chimpanzees.

In their natural habitats, chimpanzees are known to pick up seeds from feces and re-ingest them. In captivity, some practice coprophagy, which is the deliberate ingestion of feces. These behaviors are considered extremely unhygienic and gross in the human world. But, a study has shown that when it comes to others members or even close family members’ feces or bodily fluids chimpanzees are grossed out too.

In 2015, researchers from Kyoto University's Primate Research Institute went tested chimpanzees to see if they are grossed out by any of the same things as humans, particularly those that are sources of infectious disease.

The disgust response in animals evolved as a part of the defense mechanism against harmful pathogens and contaminants. According to the results of this study that continued from 2015, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, animals evolved with this system to protect themselves from pathogens and parasites, which are often associated with media or substrates that invoke our sense of disgust.

For example, bodily products and fluids are universal disgust elicitors in humans. We tend to stay away from them as a biological response. Even though we are comfortable with secretions from our body, another person’s saliva or mucus can cause a very strong negative response in our brain. But, until now we did not know whether they also elicit similar reactions in our primate cousins.

The team of researchers found evidence that exposure to biological contaminants -- ie feces, blood, semen -- via vision, smell, and touch, influences feeding choices even in chimpanzees.

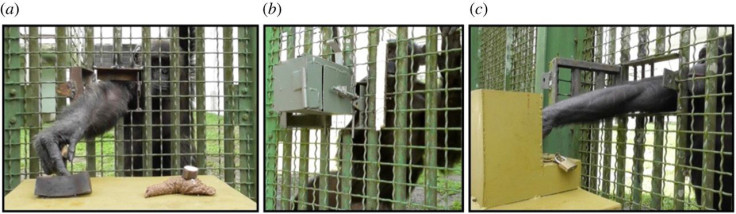

The researchers used a series of experiments to study the pattern of chimpanzees. The study found that these chimpanzees showed a considerable delay in eating food items placed atop replica feces compared to the more benign brown foam. The study also found a general; a distance that the chimpanzees maintained from the smell of potential biological contaminants; and recoil from food items associated with soft and moist substrates.

"If chimpanzees and other primates can discern contamination risk via different cues, individuals with higher sensitivities to feces and other bodily fluids may be less infected, which could have important health benefits," said Cecile Sarabian, the lead author of the study.

"Moreover, such results may have implications for animal welfare and management. We can better inform staff and keepers about the adaptive value of such sensitivity and its flexibility, as well as identify which individuals may be more at risk of infection and therefore require more attention," she added in the study.

When presented with an opaque box with food placed atop a soft and moist piece of dough, the chimps recoiled immediately after making contact with the moist material. They showed a similar response to humans reacting to moist substances that could contain pathogens.

"While anyone watching the reactions of these chimpanzees in the tactile experiments can empathize with them, it's premature to say that they feel the same as we might in that situation" cautions Andrew MacIntosh, senior author on the study was quoted in a Science Daily report. "What's great about these experiments, though, is that the observed responses are functionally similar to what ours would be, providing evidence that the mechanism underlying their behavior could be similar to ours."

"These experiments hint at the origins of disgust in humans, and help us better understand the protective function of this emotion" concludes Cecile Sarabian. "We are currently in the process of expanding our 'disgusting' work to include other primate and non-primate species," she added in the report.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.