China Banks’ Bad Debt A Cause For Concern? Not If History Is Any Guide

Bad debts are piling up in China's commercial banks, but the country will not slip into a full-blown financial crisis as long as Beijing is willing to foot the expensive bill. And according to evidence found by Chen Long at the INET China Economics Blog, the central government has already demonstrated its willingness to funnel massive fiscal reserves through four state-owned banks to avert just such a crisis.

Chinese banks’ bad loans rose for a seventh straight quarter during the April-June period, the China Banking Regulatory Commission said in a statement on its website Wednesday. That’s the longest streak in at least nine years, reflecting the difficulties facing firms amid an economic slowdown.

Non-performing loans (NPLs) climbed by 13 billion yuan ($2.1 billion) in the second quarter from the end of March, reaching 539.5 billion yuan. Soured debt increased across all lender categories, including state-owned and regional banks.

The China Banking Association, a trade group, projected in its annual report on the industry that bad loans at Chinese banks could rise by between 70 billion yuan and 100 billion yuan this year due in part to delinquency risks from industries plagued by overcapacity.

The absolute level of NPLs has been rising since early 2012, although the NPL ratio has been stable because of an offsetting increase in outstanding credit. Bad loans at Chinese banks have remained less than 1 percent of assets, according to the China Banking Regulatory Commission. To put that into context, the ratio of nonperforming loans to total assets stood at 3.9 percent in the U.S. last year. In Cyprus, the fifth euro zone country to receive bailout loans, that figure was 10.7 percent, data from the World Bank showed.

However, economists at BBVA Compass noted that it will become more and more difficult for banks to keep NPL ratios from rising by simply expanding credit, as was done last year. In addition, a number of early indicators point to a rise in NPLs, such as the increasing level of overdue loans. These overdue loans are not counted in NPLs, according the bank accounting rules.

The China Banking Association also expects smaller profits from loans and an increase in NPLs to cap profit growth at about 8 percent this year. In 2012, China's banking industry generated 1.51 trillion yuan in net profit, up 21 percent from a year earlier.

The latest data published by the China Banking Regulatory Commission on Thursday show that profit growth at Chinese banks have already slowed to 14 percent in the first half of this year, from 23.3 percent in the year-ago period.

Yet, things won’t spin out of control because China’s “bad banks” – the four state-backed asset management companies (AMCs) created in the late 1990s to buy $1.4 trillion worth of bad assets (accumulated from an earlier lending spree) from the nation's Big Four banks – are ready to step in when necessary.

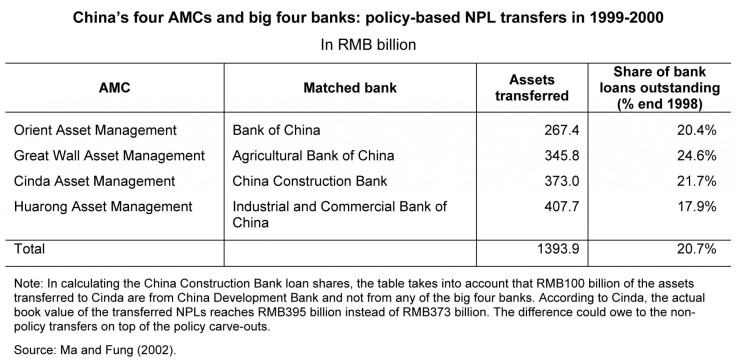

Back then, China was seeking to reform its banks and take them public as part of an effort to modernize its financial system. The amount of distressed assets was equivalent to about 20 percent of the Big Four’s combined loan books, or 18 percent of China’s gross domestic product in 1998, according to a 2003 Bank for International Settlements paper.

China Cinda Asset Management Co., Huarong Asset Management Corp., China Orient Asset Management Corp. and China Great Wall Asset Management Corp. were set up to hold the bad loans at or near face value in an explicit bailout of the Big Four -- Agricultural Bank Of China Limited (HKG: 1288), Bank of China (HKG: 3988), China Construction Bank Corporation (HKG: 0939) and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (HKG: 1398).

In exchange of the bad loans, the banks received 10-year bonds from the AMCs.

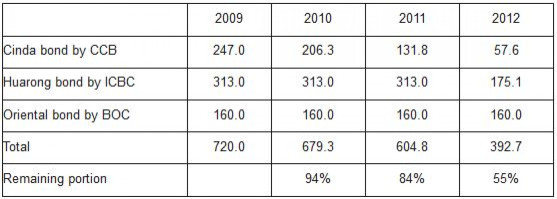

The total amount of bonds was as large as 810 billion yuan and by 2009 only about 100 billion were paid back, according to a People’s Bank of China official. So when those bonds were matured in 2009 and 2010, they were rolled over for another 10 years. The reason was quite simple: the AMCs were not making enough money to pay the principals.

Chen looked at the annual reports of the banks and noticed that the payments have suddenly accelerated since 2009.

“This is very interesting,” Chen wrote. “The AMCs were not profitable enough to pay any of the bond principals in the first 10 years so that the bonds were rolled over for another 10 years, but they suddenly started to pay large amounts right after the roll-over started.”

So why did the AMCs suddenly start to pay their bond principals after 2009? Logically, Chen said, there are only three possibilities:

- They successfully recycled cash from the bad assets so that they had enough money to pay the bonds.

- They used their retained earnings to pay the bonds.

- Someone else helped them pay the bonds.

In Chen's own words:

The financial situation of the AMCs is not very transparent but it was said that Cinda was the only AMC that was able to pay the bond interests (5.56 billion yuan per year) on time and its net profits were only 4.4 billion yuan in 2009. Therefore there is no way that Cinda can pay bond principal as much as 190 billion yuan unless it suddenly made tremendous progress in selling those bad assets. What’s more, since Huarong and Oriental could not even pay interest on time, tremendous progress would be required for Huarong to pay 140 billion in a single year. They did make some progress -- Cinda’s net profits in 2012 rose to 7.27 billion yuan while Huarong’s net profits increased to 6.96 billion yuan -- but this number is still too small.

Can they use retained earnings to pay the bond principal? Given that Cinda's net profits were 7.27 billion yuan in 2012, even under the most optimistic estimation its retained earnings can hardly reach 100 billion yuan. So it is impossible for them to pay 190 billion principal with retained earnings. Since Huarong is even less profitable than Cinda, it is even more unlikely that it will pay 140 billion yuan in a single year.

There leaves the third option: someone else is paying for Cinda and Huarong. But who?

Chen thinks the deep-pocket is the Ministry of Finance. One piece of evidence Chen found was this announcement published in August 2010.

But why did the central government wait till 2010 to help pay AMC bonds? Why didn’t the Ministry of Finance offer any help before 2009, when the AMCs weren’t able to pay the bonds? If the AMCs still can’t pay, the bonds can either be rolled over again or the banks can write them off from their balance sheets.

“Why is the government (the taxpayers in fact) bailing them out now?” Chen said. Given the amount of inside information and secret talks involved, it’s hard to know the exact reason. But Chen suspects this move has something to do with the government’s plan to list Cinda on the Hong Kong exchange.

Cinda is expected to launch an initial public listing in Hong Kong in late 2013 or early 2014, the South China Morning Post reported on Tuesday, citing anonymous sources. Cinda is hoping to raise about $2 billion in the IPO. Merrill Lynch, Credit Suisse Group AG (NYSE:CS), Goldman Sachs Group Inc (NYSE:GS) and UBS AG (NYSE:UBS) are likely to be hired as Cinda's initial public offering (IPO) underwriters.

Cinda has planned for an IPO in Hong Kong for a long time, but it will be a tough-sell with 247 billion payable bonds that have been rolled over for 10 years. Commercial banks will also want to get paid as soon as possible because they don’t want to hold hundreds of billions in bonds with an annual return of only 2.25 percent while the benchmark lending rate is 6 percent and even the yield 10-year government bond is above 3.5 percent, Chen noted.

“Everyone seems happy with the solution, and it tells us again that central government will bail out large financial institutions when they are in trouble,” Chen added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.