China Races To Find Virus Vaccine, Put Scandals In The Past

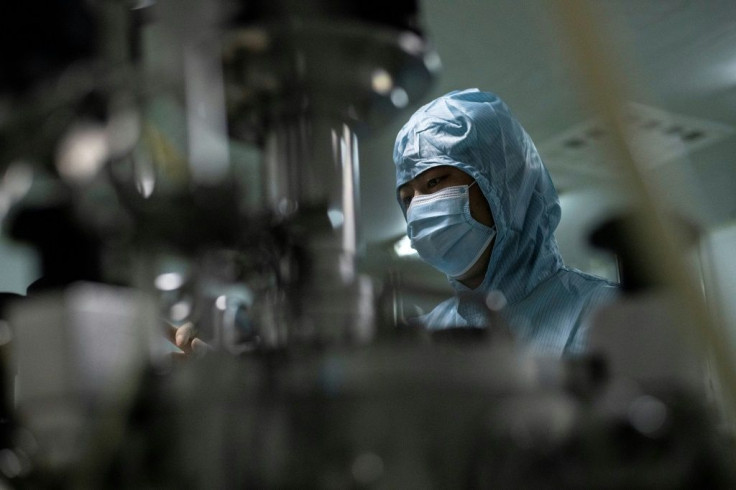

China has mobilised its army and fast-tracked tests in the global race to find a coronavirus vaccine, but its labs also have an image tarnished by past health scandals to overcome.

Six months after the first cases emerged in the city of Wuhan, China has moved quickly to develop a vaccine and is involved in several of the dozen or so international clinical trials currently under way.

Researchers have reported promising early results from tests on humans and monkeys, and authorities hope to have the first shots ready for the public this year.

The Military Academy of Medical Sciences is among those working on a vaccine, in partnership with a pharmaceutical firm.

China has authorised fast-track procedures, allowing preclinical phases -- such as animal tests and other studies -- to be conducted at the same time instead of one after the other.

But Ding Sheng, dean of the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Beijing's Tsinghua University, sounded a note of caution around using "non-conventional methods".

"I understand that people are eagerly waiting for a vaccine," Ding said in the People's Daily, a Communist Party organ.

"But on a scientific point of view, we can't lower our criteria, even in an emergency," he said.

Ding also questioned the decision to authorise phase one and two clinical trials at the same time, allowing labs to avoid having to seek authorisation before proceeding from one to the other.

Nick Jackson, of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), however, pointed out that China was not the only country to do this.

"Many organisations globally are conducting adaptive trials that allow for rapid transition from phase one to two studies," said Jackson, whose organisation funds research into vaccines.

"This approach is necessary given the urgent need for vaccines."

One pharmaceutical company, Sinopharm, said its vaccine could be ready for the public at the end of the year or early 2021.

The head of China's Centre for Disease Control and Prevention hopes a vaccine could be ready as early as September for priority cases, such as health workers.

But China will also have to convince the public that any vaccine it produces are safe as the country's pharmaceutical industry has been hit by scandals involving tainted medicine and corruption in recent years.

Parents have held protests and some are scared enough to seek foreign-made vaccines for their children over those made in China.

One of the biggest scandals involved Changchun Changsheng Biotechnology, which was fined a record $1.3 billion in 2018 after it fabricated records for a rabies vaccine for humans.

The same company had also produced a vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough (DPT) that was administered to more than 200,000 children and caused paralysis in a few cases.

One of the companies involved in the search for a vaccine against the novel coronavirus was implicated in the scandal.

The Wuhan Institute of Biological Products, from the city where the virus first emerged late last year, produced 400,000 doses of DPT that "did not meet the norms", according to drug regulators.

The government responded by enacting legislation to tighten oversight and prevent defective shots from entering the market.

"The government is very careful in reviewing the vaccine applications," said Lung-Ji Chang, the American president of the Geno-Immune Medical Institute in Shenzhen, southern China, which is also working on a coronavirus vaccine.

But several other cases have been reported by Chinese media in the past year, including fake vaccines in a southern hospital and children getting shots for the wrong illness in northern Hebei province.

"This does not mean (China) does not have the capability to produce a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine," said Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations think tank in the United States.

He noted that China now has tougher laws, vaccines recognised by the World Health Organization and more money invested in research and development.

In a show of confidence, a general and senior staff at Sinopharm were injected with a candidate coronavirus vaccine currently under development.

"I think the last thing the Chinese government wants is to distribute a flawed vaccine," Huang said.

"You could imagine how news of severe adverse reaction associated with a Chinese-made vaccine will damage the regime legitimacy and international reputation."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.