China’s Third Plenary Session Of 18th CPC Central Committee: 8 Things To Know About China’s Party Congress And Its Reform Agenda

A year after a new generation of leaders took over at the helm of China’s Communist Party, the forthcoming party congress is seen as a springboard for significant changes and a key test of President Xi Jinping’s commitment to economic reform.

China’s ruling Communist Party will hold the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee Nov. 9-12 in Beijing.

“Third Plenums have been the launch-pad for many of China’s major reforms. Now, with the leadership suggesting that a ‘master plan’ will be unveiled in November, expectations are understandably high,” wrote Capital Economics' Mark Williams and Julian Evans-Pritchard in a note to clients.

Here is what you need to know about the 2013 Third Plenum:

1. What exactly is this meeting?

The upcoming meeting is a plenary session of the Party’s Central Committee, the body from which the Politburo is drawn. The Central Committee is elected for a five-year term, with the current group (the 18th) in place since the leadership handover late last year. During its five-year term, the Committee holds a number of meetings (plenums) where it discusses and approves big policy decisions. While other plenums deal with areas such as ideology and propaganda, the third one usually focuses on economics. President Xi will be hosting next week’s meeting, which will gather 376 of the top party leaders.

2. Why is the Third Plenum important?

While not all Third Plenums are created equal, they sometimes can be a big deal.

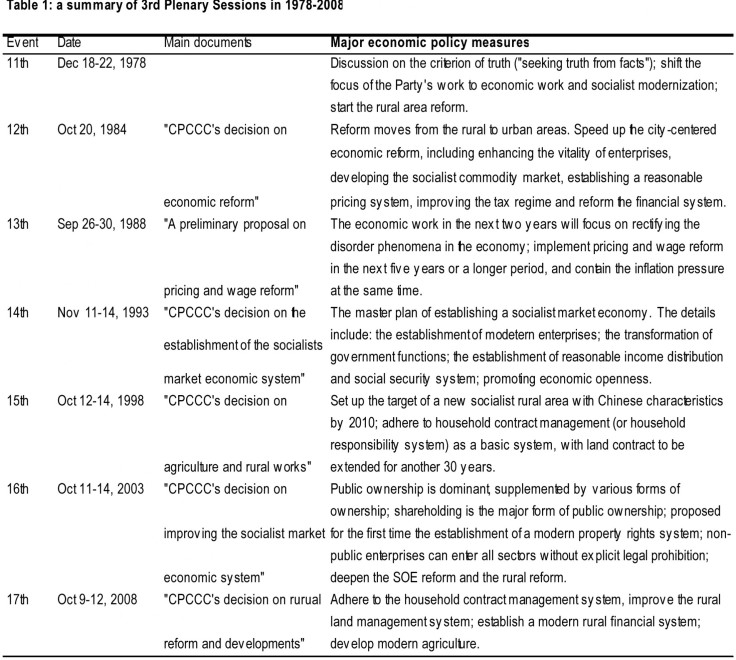

The most-talked-about Third Plenum in China’s history took place in December 1978 and marked the beginning of market reform. In 1993, the 13th Third Plenum endorsed the “socialist market economy,” which laid the foundation for the series of fiscal, state-owned enterprise (SOE) and banking sector reforms driven through by former Premier Zhu Rongji.

“People tend to attach special importance to Third Plenums mainly because they wish that the current leadership can courageously roll out structural reforms to address many of China’s problems,” said Ting Lu, an economist with Bank of America-Merrill Lynch, in a note.

3. Expectations are running high for this year.

Despite some suspicions and doubts, expectations for this year’s meeting are high.

“Domestically, there is a sentiment, especially among the reform-minded elites, academics, and professionals, that the past 10 years were considered a ‘lost decade’ due to the lack of significant economic and political reforms,” China economists Jian Chang said in a note.

“With the state sector growing at the expense of the private sector, and that ordinary people are not getting their fair share from China’s fast growth, some argue that not only was there little progress in some areas, but in others there was clear regression,” Chang added.

Against this backdrop, China’s once-in-a-decade leadership transition, completed in November 2012, has raised expectations for a new round of reforms.

Many experts expect major economic reforms plans to be announced at the meeting. On Oct. 27, the Development Research Center of the State Council (DRC), a key government think tank, released its proposal for the reform framework, which has been dubbed the “3-8-3” project.

The plan highlighted: 1) three key themes -- improve the market system, transform the role of government and build an innovative corporate structure; 2) eight key reform areas -- government, monopoly sectors, land system, financial sector, tax system, management of state assets, innovation and further opening-up of the economy; and 3) three areas of breakthroughs -- open up, social security reform and land reform.

4. But those looking for detailed reform plans will likely be disappointed.

“Beijing has certainly talked the talk of changes and the hope is for the new leaders to walk the walk,” Societe Generale's economist Wei Yao said in a note.

If the new leadership were to execute this bold plan, it would certainly be a major positive to China’s long term prosperity as well as short-term business confidence. However, economists caution that the roadmap to be delivered at the plenum may be notably less aggressive. The DRC has a reputation of representing the most reform-minded faction of the government.

China-watchers see two major barriers to crafting a sweeping reform package at the upcoming meeting: 1) The new leadership still needs more time to consolidate its power; 2) Vested interest groups formed in the past three decades could block meaningful reforms even if those reforms could benefit all parties in China in the long term.

According to Bank of America-Merrill Lynch’s Ting Lu, China’s unique political system implies that it takes several years for new leaders to replace key government officials with their own protégés. Current leaders’ predecessors (former President Hu Jintao and former Premier Wen Jiabao) took almost five years to accomplish this task, and in hindsight people still believe that Hu and Wen’s power were significantly constrained even in their second term spanning 2008-13.

“The serving President Xi and Premier Li Keqiang could do much faster and better in this regard, but at less than one year into their new roles, they have not yet had enough time to deliver a comprehensive reform package,” Lu said.

Also, reform strategies aiming at protecting or forgiving vested interests could be resisted by the people. In return, those vested interest groups might staunchly resist any reforms which could endanger their interests.

5. Given the barriers, why are analysts still hopeful of reforms?

China’s political leaders know the consequences of not reforming. They know very well that without tackling the tough issues, it is unlikely China can sustain economic growth and maintain social harmony.

“We have been positive on Xi-Li’s determination and ability to push through reforms. Compared with their predecessors, China’s new leaders, both of whom had formerly been provincial governors, are younger, better educated and have global visions,” said China economists Jian Chang.

6. How will the new blueprint affect China’s economic growth?

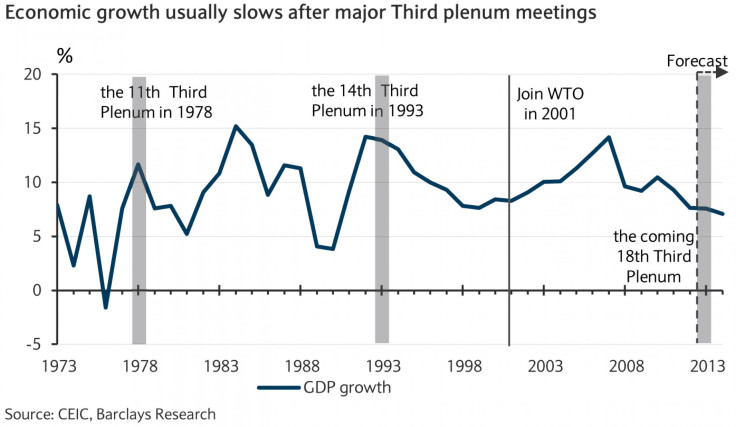

China economists Jian Chang observed that economic growth tends to slow in the years following the Third Plenum meetings, which reflects the fact that structural reforms, while good for the longer term tend to slow growth in the short term.

Whether or not the government will lower the 2014 gross domestic product growth target to 7.0 percent from 7.5 percent will be one of Barclays’ gauges for the leaders’ tolerance for short-term pain (lower growth) to achieve a rebalancing toward a consumption-led economy.

7. Areas that are unlikely to be featured in next week’s meeting.

Economists expect no reforms on state-owned enterprises, especially central government SOEs. “Many in the government accept that SOEs are at the root of many serious structural problems. But they also see the state sector as a key tool for preserving the Party’s control (and a means of self-enrichment) that they will be reluctant to give up,” said Capital Economics’ Williams.

Major breakthroughs in the Hukou system, especially for top-tier cities, as well as looser regulation on prices of some key utilities such as water, gas and electricity, are also not expected.

8. What might be addressed?

Economists at Barclays put together a nice handy summary.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.