Christianity Spread In Iceland, Helped By Largest Volcanic Eruption In Country

It is easy to draw a connection between the imagery of hell, as written in the Bible (think “fire and brimstone”) and the real-life phenomenon of volcanic eruptions that take place on Earth (the fact that some may consider the planet itself hell doesn’t make it the biblical hell). Fire, the smell of sulfur, and lightning all occur when volcanoes erupt, and Christian preachers have invoked the imagery when exhorting masses to repent for their sins or face eternal damnation.

As it turns out, this was used very effectively in the 10th and 11th centuries in the conversion of Iceland to Christianity from the paganism that was followed there earlier, or so a new study suggests. This was based on the study of ice cores and tree rings to establish the time when the largest lava flow in Iceland’s history occurred, and a look at the most celebrated medieval poem from the country, Vǫluspá.

The Eldgjá volcano is in southern Iceland whose volcanic canyon, or fissure, is the longest in the world, at 40 kilometers (about 25 miles). An eruption in the 10th century caused the largest lava flood — an otherwise rare type of volcanic eruption that is common in Iceland — in the country’s recorded history. A lava flood is a “prolonged volcanic eruption in which huge flows of lava engulf the landscape, accompanied by a haze of sulfurous gases,” and the massive eruption over 1,000 years ago would have spewed enough lava to cover the entire island nation in a layer 20 centimeters deep.

The island was settled by Vikings and Celts in about 874 CE, and using evidence of volcanic fallout, as recorded in ice cores from not-too-distant Greenland, researchers — led by Clive Oppenheimer from the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom — concluded that the Eldgjá eruption “began around the spring of 939 [CE] and continued at least through the autumn of 940 [CE].”

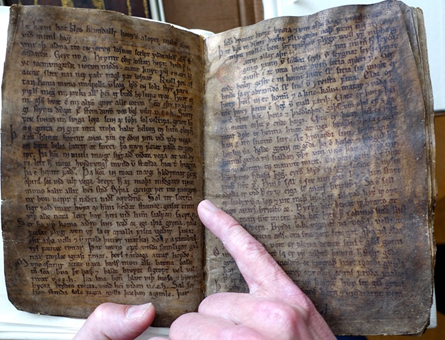

Called “The prophecy of the seeress” in English, Vǫluspá was written at least as far back as 961 CE, and describes what are likely the eruption and its aftermath, and is the only known text from Iceland to do so.

“The sun starts to turn black, land sinks into sea; the bright stars scatter from the sky.

Steam spurts up with what nourishes life, flame flies high against heaven itself.”

Vǫluspá also speaks of cold summers that followed the massive eruption (volcanic ash covered the sky, reducing the amount of sunlight that reached Earth, causing widespread loss of livestock and farmland, particularly in Iceland itself, but felt in most places across the planet) and all the end-of-the-world imagery was used in prophesizing the exit of the many pagan gods, and the coming of a singular god.

Since the conversion of Iceland to Christianity was formalized some 30 to 50 years later, researchers suggested the poem used apocalyptic imagery “to rekindle harrowing memories of the eruption to stimulate the massive religious and cultural shift taking place in Iceland in the last decades of the tenth century.”

“The poem’s interpretation as a prophecy of the end of the pagan gods and their replacement by the one, singular god, suggests that memories of this terrible volcanic eruption were purposefully provoked to stimulate the Christianisation of Iceland,” Oppenheimer said in a statement Monday.

The open-access paper, coauthored by researchers from other European countries, as well as some from the United States, appeared online Monday in the journal Climatic Change, titled “The Eldgjá eruption: timing, long-range impacts and influence on the Christianisation of Iceland.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.