Christians Around The World: A History And Timeline Of Coptics In The Middle East

On Palm Sunday, April 9, the Islamic State targeted two Coptic churches in coordinated bombings in the Egyptian cities of Tanta and Alexandria. The explosions killed dozens of Egyptians and injured many more in the worst of a number of such attacks that have taken place in the last decade.

The interrelated challenges of violence, economics and discrimination have led to the increasing departure of Christians from the Middle East. For centuries they have been part of the rich religious diversity of the region.

So who are these people that National Geographic has called “The Forgotten Faithful”?

Coptic history

Among the Christians of the Middle East, the largest number – some eight million or so – is made up of Egypt’s Copts. Since I first visited Egypt in the 1990s, I have been interested in this community and its contribution to pluralism.

Copts are the indigenous Christian population of Egypt, who date back to the first decades following the life of Jesus Christ. The biblical Book of Acts tells how Jews from Egypt came to Jerusalem for the feast of Pentecost, a Jewish harvest festival that marked the birth of the Christian church merely weeks after Christ’s crucifixion. Many of these Egyptians took the message of Christianity back to their own country. Christian tradition holds that St. Mark, one of the early disciples of Jesus, became the first bishop of Egypt.

By the fourth century, the majority of Egyptians had embraced the Christian faith. Even after the Muslim conquest in the seventh century, the majority of Egyptians were still Christians. It was only during the Middle Ages that greater and greater numbers embraced Islam, and the Christian population dwindled.

Today, Egyptian Christians make up approximately 5 to 10 percent of the Egyptian population. The word “Copt” is used for all Egyptian Christians. It is derived from an ancient Greek word that simply means “Egyptian.”

Copts are fiercely proud of their Egyptian heritage that dates back to the age of the pyramids as early as 3000 B.C. The vast majority of Copts are members of the Coptic Orthodox Church, an independent church that arose in A.D. 451, long before the divide that created the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches in 1054.

The language of the Coptic Orthodox church service (or liturgy) used in daily worship is also known as Coptic. It is the original Egyptian language written in Greek script.

Copts live throughout every corner of Egypt and at every socioeconomic level. One of Egypt’s richest men, Naguib Sawiris, is a Copt, and so are most of Cairo’s garbage collectors, the zabellin. Though Copts are largely indistinguishable from the Muslim majority, many are given tattoos of a cross on their wrists as children, signifying their permanent commitment to the community. In addition, Coptic women are unlikely to veil, making them stand out from Muslim women.

The head of the Coptic Orthodox Church, and the most significant Christian leader in Egypt, is the bishop of the See of St. Mark, known among Egyptians as the Coptic pope or patriarch. Today the Church is led by Pope Tawadros II, who studied pharmacy before deciding to pursue a religious career in the 1980s.

Religious practice

Copts practice a form of Christianity that hearkens back to the earliest traditions of the church.

Pope Tawadros and all of the bishops of the Coptic Orthodox Church begin their vocation as monks – celibate men living in seclusion in monasteries. The Coptic Orthodox Church is unique in its preference for placing monks in the highest positions of authority.

In fact, the world’s first Christian monks, St. Anthony and St. Paul, established their monasteries in the eastern desert of Egypt in the early fourth century. Both of these monasteries, and numerous others, continue to operate.

In his book “Desert Father,” Australian author James Cowan describes how the monastic tradition became an important support for Egyptian Christians under persecution and helped to preserve culture throughout the Christian world.

Modern-day Copts often visit the monasteries for spiritual guidance, community retreats and to rediscover their heritage.

But while Copts may go to the deserts of Egypt for their religious practice, most live in the cities among their Muslim compatriots. Their churches and community service organizations – and even Coptic news sites and media – contribute to the vibrancy of Egyptian social and intellectual life.

Peter Makari, a church leader with extensive experience working with Coptic organizations, writes about the ways in which Copts have organized community initiatives, development projects and solidarity movements with fellow Egyptians to promote national unity and peace. Copts regularly celebrate feasts with Muslim leaders and host public dialogues with Muslim intellectuals and leaders.

In particular, Copts participated alongside their Muslim compatriots in the protests that brought down the authoritarian rule of former President Hosni Mubarak in 2011.

The condition of Copts today

Nonetheless, Copts have faced systemic discrimination in employment and limitations on their ability to access public services and education ever since the establishment of the modern republic of Egypt in 1952.

Governing authorities made it very difficult for them to build or refurbish their churches. After the 2011 revolution, Copts initially enjoyed newfound freedoms to organize and voice their concerns about these practices.

However, their aspirations were dashed when the Egyptian Armed Forces clashed with Coptic protesters in a deadly confrontation in October 2011. When subsequently the Muslim Brotherhood came to power in 2012, there was an attempt to push through a constitution that gave special powers to Islamic authorities. These developments seemed to undermine Copts’ ability to participate as equal citizens.

Most Copts were therefore content to see the restoration of authoritarian rule under Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, who in 2014 introduced a new constitution that limits the role of Islam in Egyptian government.

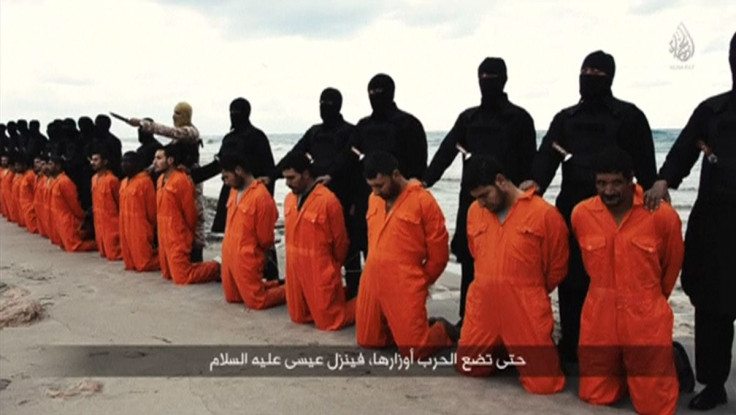

Unfortunately, the Coptic community has now become an easy target in the fight between al-Sisi and his Islamist enemies. Violent attacks on Copts have led them to flee certain areas of Egypt, such as Sinai, and there is a steady stream of Coptic emigration from Egypt.

This must concern all Egyptians, since the presence of Copts is essential to the health of intellectual, cultural and political life in the Middle East.

Paul Rowe, Professor and Coordinator of Political and International Studies, Trinity Western University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.