Christo, Master Of The Monumental Wrap-up

From Paris's oldest bridge to Berlin's Reichstag, Bulgarian-born US artist Christo spent decades wrapping landmarks and creating improbable structures around the world.

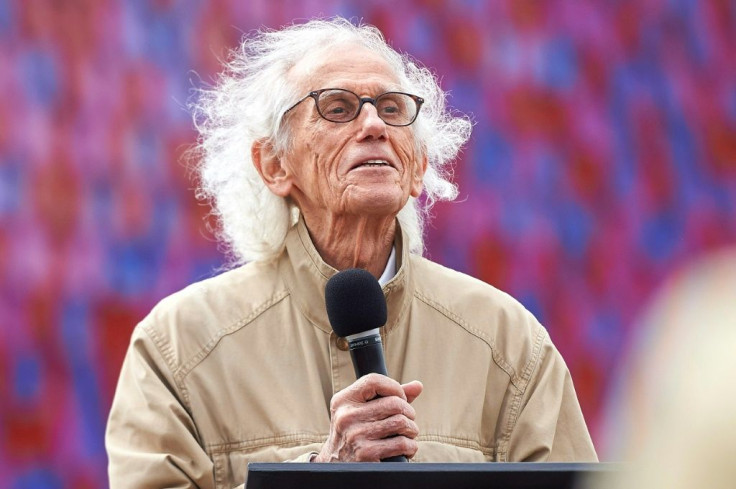

Christo, who died on Sunday in New York at the age of 84, collaborated with his wife of 51 years, Jeanne-Claude, until her death in 2009. Afterwards, he continued to produce dramatic pieces into his 80s.

Their large-scale productions would take years of preparation and were costly to erect: but they were mostly ephemeral, coming down after just weeks or months.

"Totally useless," said Christo of their work in the 2019 documentary, "Walking on Water".

"Art is all about pleasure. Visual pleasure is very important -- very invigorating, very engaging," he told The New York Times in 2016.

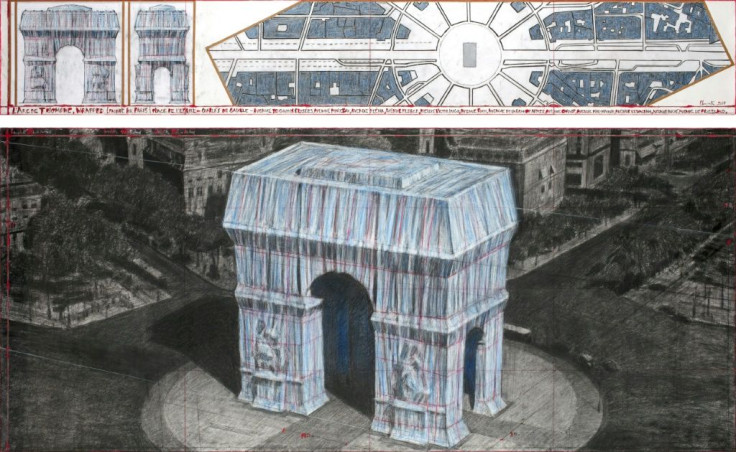

Gaunt, bespectacled, his long hair becoming wispy and white in age, Christo had been planning to cover Paris' Arc de Triomphe in silvery-blue recyclable material in 2021 to coincide with a retrospective at the city's Pompidou Centre.

The statement from his office Sunday announcing his death said that, in accordance with his wishes, that project would go ahead and was on schedule for September next year.

Born in 1935 in Gabrovo, Bulgaria, Christo Vladimiroff Javacheff fled the communist regime in 1956 aboard a goods train.

Arriving in Paris, he mixed with artists such as Yves Klein and Niki de Saint-Phalle, and dabbled in abstract painting.

He met Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon in 1958, as he was doing a portrait of her mother, and they married the same year.

Their work was collaborative but they at first called themselves just Christo, creating the impression that their production was his alone.

Their son Cyril was born in 1960 and the family moved to the United States in 1964, Christo obtaining US nationality in 1973.

Their first large-scale public installation appeared in 1968 when the couple wrapped Swiss art museum the Kunsthalle, in Berne, in 2,430 square metres (26,160 square feet) of fabric.

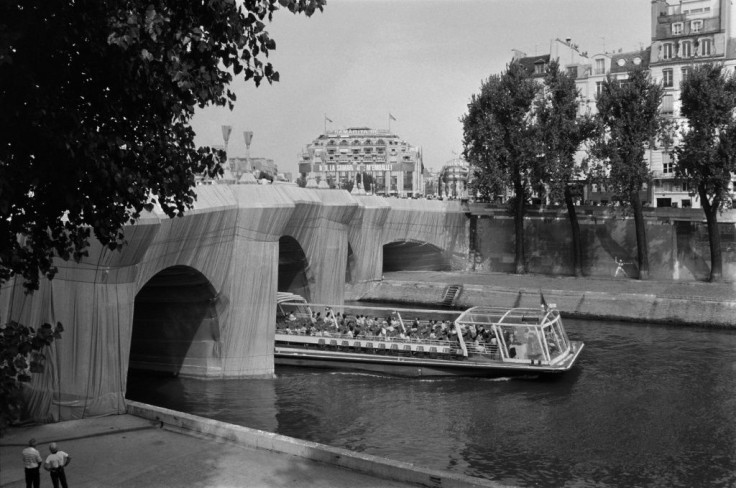

Among the most famous of similar works across the world were the Pont Neuf in Paris which was entirely draped in silky sandstone material in 1985, and 10 years later Germany's Reichstag covered in silvery shimmering fabric.

There have been islands surrounded in floating pink material, an Australian beach covered in white, and a 39-kilometre-long (24-mile) cloth fence through the Californian hills.

The cost of these temporary installations can be astronomical.

"The Umbrellas" in 1991, for example, cost $26 million, entirely financed by the artists, according to their website. The simultaneous installation in California and Japan of hundreds of giant blue and yellow umbrellas was dismantled after 18 days.

Christo never accepted sponsorship, funding the projects through the sale of his sketches, collages, scale models and original lithographs.

The installations also required permits that could take lengthy negotiations to secure. Over 50 years, just 22 had been achieved by 2011 with 37 not receiving official permission, according to the website.

Some of the work has been controversial: the Reichstag wrap-up required a vote by German deputies, getting 292 in favour and 223 against.

But the uncertainty and intense collaboration required each time were all welcome parts of the adventure.

"I think it would be absolutely boring to work the way many artists do," Christo said in The New York Times in 2014.

The temporary quality of the productions was also important to the artist.

When asked by Berlin authorities to prolong the Reichstag cover-up beyond its 14 days, Christo refused.

"It is a kind of naivete and arrogance to think that this thing stays forever, for eternity," he said in an interview with the Journal of Contemporary Art in 1991.

"All these projects have this strong dimension of missing, of self-effacement... they will go away, like our childhood, our life.

"They create a tremendous intensity when they are there for a few days."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.