Colombian Village Offers Hope For Indigenous Gay Men

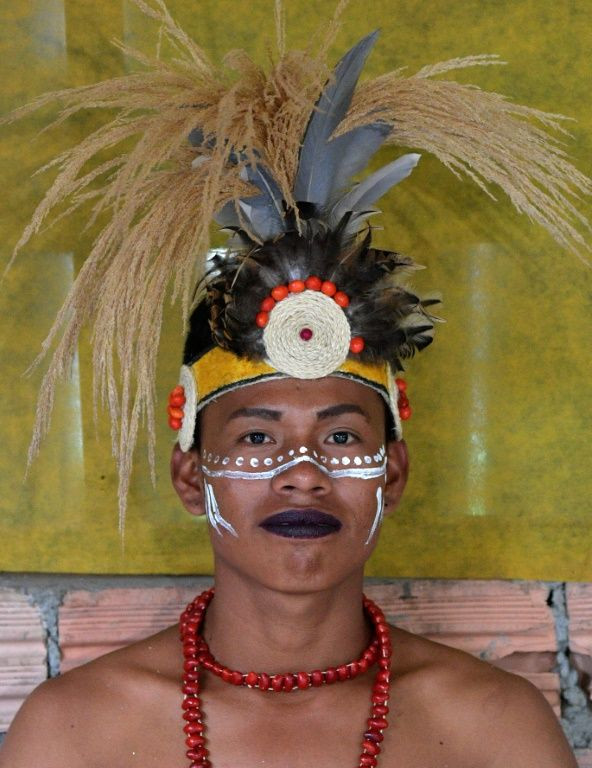

Growing up in an indigenous village in the Colombian Amazon, Junior Sangama long hid his sexuality -- before clashing with his family and choosing to leave.

But the 27-year-old has since returned home, one of a number of gay residents who have found a place, of sorts, in the deeply conservative community of Nazareth.

It's a remote settlement with just over 1,000 residents who survive on farming and making handicrafts, and where LGBT people were once forcefully rejected.

In recent decades, the community's leaders said they have halted cruel anti-gay punishments and offered a measure of refuge, but with caveats for about 20 gay residents like Sangama, Saul Olarte and Nilson Silva.

In exchange for the right to live within the community -- a crucial issue in the indigenous worldview -- they have set themselves certain restrictions.

They refrain from kissing in public or living together under the same roof.

Sangama, a member of the Tikuna indigenous group, initially made the tough decision to leave so he could be himself.

"Before coming out of the closet, I never displayed very effeminate behavior -- I did that when I was outside" the community, he said.

Olarte also left while Silva did so for more than a year to perform military service in the regional capital Leticia, which is about an hour away by boat.

"My father rejected me... but I followed my path," said 23-year-old Silva.

The men have taken on a role in preserving local heritage by performing a traditional dance that begins with the burning of incense and a beat drummed out on a hollow turtle shell.

"Within the community, we, as LGBT people, are the ones who inculcate and support cultural activities," said Olarte, 33, who heads a 12-strong dance troupe.

Yet when they returned, all three opted for discretion with the knowledge of how gay people were treated in the past by the Tikuna -- one punishment was being forced to endure painful insect bites.

Alex Macedo, spokesman for the indigenous council, said that according to local belief, a "person is regenerated in thought and in (physical) fortitude" through the bite of a certain yellow ant.

People were also made to cultivate the ground or build canoes to test their "masculine side," said Macedo, 40, who insisted these punishments no longer exist.

At the turn of the 21st century, there was a move "within the community to not have any form of discrimination," said Macedo.

Since then Nazareth has become a place where LGBT people from other indigenous communities can build a life.

Macedo said it was decided that these young men were needed "to conserve the culture, especially the maternal language."

Historically victims of exclusion and attacks on their culture, indigenous people make up 4.4 percent of Colombia's 50 million population.

Unlike other indigenous groups, those settled along the Amazon are more wary of "westernization" and see the LGBT cause as one imposed on them, said Wilson Castaneda, director of the Affirmative Caribbean Corporation, which advocates for the rights of sexual minorities.

Sexual diversity is thus an invisible phenomenon in many Amazonian indigenous communities, but Castaneda says it would be unfair to brand them as homophobic.

"They've dealt with different sexualities without violence" even though there's no "acknowledgment, nor complete inclusion," he said.

Nazareth is a case in point, given that local leaders won't accept an open LGBT community.

"They can be like this: loosely grouped, as they are now... but they won't be allowed to form a group," said Macedo.

Sangama is looking farther down the road, saying that one day, they will be able to have "a partner and a dignified home within the community and express themselves freely."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.